Exploiting Ruby’s Object Model to Ease Collaboration

One of the common patterns I use in my day-to-day Ruby coding is to define a module or level call method. I like to establish these call methods as crisp interfaces between different concerns.

Dependency Injection with Objects That Respond to Call

In the following example I’ve constructed a “Package” class that has a deliver! method. Let’s take a look:

module Handler

def self.call(package:)

# Complicated logic

end

end

module Notifier

def self.call(package:)

# Complicated logic

end

end

class Package

def initialize(origin:, destination:, notifier: Notifier, handler: Handler)

@origin = origin

@destination = destination

@handler = handler

@notifier = notifier

end

attr_reader :origin, :destination, :handler, :notifier

def deliver!(with_notification: true)

notifier.call(package: self) if with_notification

handler.call(package: self)

end

end

If I want to test the deliver! method I have a few scenarios to consider:

- I’m not sending a notification

- I’m sending a notification and it raises an exception

- I’m sending a notification and it succeeds

And let’s assume that both Notifier.call and Handler.call are very expensive to run in test. Without stubbing or mocking, I could write the following test:

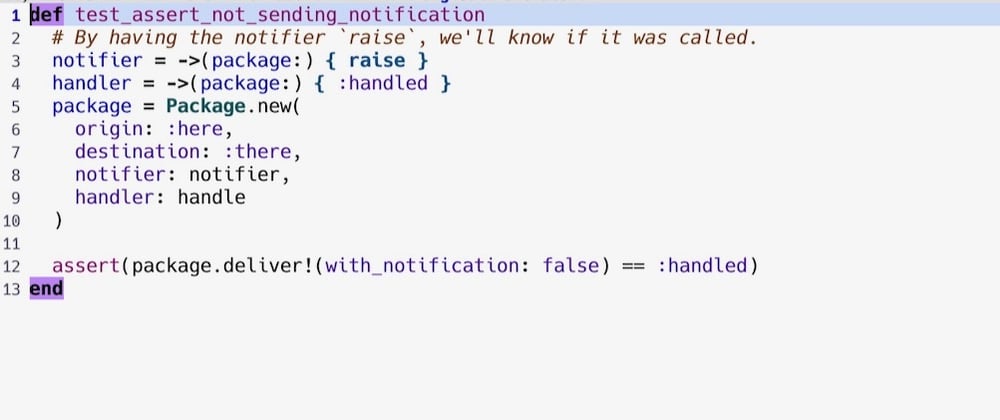

def test_assert_not_sending_notification

# By having the notifier `raise`, we'll know if it was called.

notifier = ->(package:) { raise }

handler = ->(package:) { :handled }

package = Package.new(

origin: :here,

destination: :there,

notifier: notifier,

handler: handle

)

assert(package.deliver!(with_notification: false) == :handled)

end

Dependency Injection Using a Collaborating Object’s Method as a Lambda

There are some interesting pathways we can now go down. First, what if we really don’t like the .call method naming convention?

module PlanetExpress

def self.deliver(package:)

# Navigates multiple hurdles to renew delivery licenses

end

end

We could create an alias of PlanetExpress.deliver but we could also do a little bit of Ruby magic:

Package.new(

origin: :here,

destination: :there,

handler: PlanetExpress.method(:deliver)

)

The Object.method method returns a Method object, which responds to call. This allows us to avoid modifying the PlanetExpress module, while still enjoying the flexibility of a call based interface.

This is perhaps even more relevant when I think about interfacing with ActiveRecord. Are there cases where I want to have found a record and process it? Maybe the creation of that record is expensive. Let’s short-circuit that.

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

end

# An async worker that must receive an ID, not the full object.

class CongratulatorWorker

def initialize(user_id:, user_finder: User.method(:find))

@user = user_finder.call(user_id)

end

def send_congratulations!

# All kinds of weird things with lots of conditionals

end

end

With the above, I can now setup the following in test:

def test_send_congratulations!

user = User.new(email: "hello@domain.com")

finder = ->(user_id) { user }

worker = CongratulatorWorker.new(user_id: "1", user_finder: finder)

worker.send_congratulations!

end

In the above scenario, I’d be scratching my head if I saw a User.call method declared in the User class. But in the CongratulatorWorker I would have a bit more of a chance of reasoning what was going on.

Using a Method Object as a Block

This example steers in a different direction, but highlights the utility of the convention of having a call method.

module ShoutOut

def self.say_it(name)

puts "#{name} is here"

end

end

["huey", "duey", "louie"].each(&ShoutOut.method(:say_it))

I was hoping that I could define call on ShoutOut and use that as the block (e.g. .each(&ShoutOut)). But that did not work.

Conclusion

This degree of dynamism is one aspect I love about Ruby. And it’s not unique to Ruby; I do this in Emacs-Lisp.

Early in learning Ruby, I stumbled upon a few statements that inform Ruby:

- Everything’s an Object

- A Class is an Object and an Object is a Class

And even the methods on an Object are themselves Objects. What’s nice about that is these objects have shape and form; you can see that in “detaching” the method and passing it around.

Top comments (5)

While I appreciate the idea of using

callmethod in unexpected places, I can't help but wonder if this will be more confusing for those reviewing or reading the code. As a rubyist when I seesomething.callI assume that something is a proc, lambda or a method object. I might even use the shorthand version ofsomething[]to invoke it. But if the object in question isn't a proper callable, this might not work.Second point is that this pattern does not solve the fact that we still have tightly coupled classes

PackageandHandler➔ they must know about each other. There is no way to test thedeliver!method without invoking both objects.IMHO this type of problem can be well addressed by using Events as first class citizens, and using the Observer pattern on steroids to decouple the caller from the downstream processing.

Here is a version of your code using the gem

ventablewhich does exactly that — an easy way to create event classes, subscribe various modules or classes to each event either during the application initialization, or dynamically at runtime:I admit that the

ventablegem is my creation. It's actually pretty small if you look at the source.There is a much more expansive and feature-rich event-driven gem called Wisper which can be configured to even execute event handlers in the Sidekiq background jobs with wisper-sidekiq

I wrote a blog post a while ago about detangling Rails logic using events and observers. I believe it is as relevant today as it was back then.

That said, it's always good to think out the box about how various ruby conventions came to be.

Memoization is definitely a valid approach; and alas we're working with a very arbitrary object, so

One subtle bonus of DI is that the yard docs will have some guidance on the assumptive collaboration. Which in turn provides some LSP help.

Now, whether that is good guidance (with the expanded API) or not is certainly up for a debate. I had personally considered those two named and defaulted parameters as somewhat of a "private API". But that's also not clear.

Quite a bit to think about.

I knew this was possible, and forget the Proc route. Thanks for the reminder!

There is a

.()syntax for sending:callto an object, if you like syntax shortcuts. I never do this personally, but it's thereIt's almost just right, and just a little bit wrong. I think Trailblazer did this early on, but may be moving away from it.

am I wrong or there's a typo on the first example? On

shouldn't it be?