I'd like to document and step through the execution of a simple concept in Python: creating an automatic HTML reporting tool.

The outcome would be a single stand-alone HTML file. An HTML file is a great reporting tool: even stripped of a back-end server, you can package up a good volume of info in a page and have handy-dandy interactivity.

Now, to be fair: this is not a terribly exciting or sexy project. All the same, automatically producing reports is a fantastic trick to have up your sleeve, especially in business environments. Automate the boring stuff, as they say.

Personally, I mainly intend to use this to automate reporting of model performance in the machine learning space, but you could of course use this for any context!

Naturally, tools like this already exist. But I want to make my own, for the experience and flexibility it offers me.

How is this guide presented?

Rather than just providing a dump of code that works, I'd like to incrementally work through the development, step-by-step. You'll see what I see - code what I code!

Personally, I've always found this kind of tutorial more effective as:

- It gives an insight of how someone else approaches a problem

- It actually reflects how I code - feature by feature, commit by commit.

Who is this for?

A user "knee-deep" in Python is assumed. I'll not run over standard syntax and the like, but I'll be sure to stop and explain anything particularly tricky. Wherever possible, I'll refer back to cleverer and clearer explanations.

Step Zero - Stop for a minute

I'm actually a chemical engineer by background. While I certainly gained and applied a lot of useful and/or esoteric knowledge from this background, by far the most useful bit of advice I ever learnt was probably also the most simple:

When approaching a new problem, draw a picture.

By "draw a picture", I mean to externalise the problem. Sketch it out and get thoughts and ideas out on paper.

Before tackling this (relatively small-scale) project, I sat down and spent 10-15 minutes sketching out how I thought I might approach it, what parts would move, what parts would stay static, and a (very) rough structure of the project.

My own nigh-incomprehensible sketch is as follows.

Some key learnings from early planning

Based on my early "planning", some things came clear:

- An HTML templating system makes a lot of sense. These systems are designed to input dynamic content into static template: this sounds exactly like what we're after. In Python, Jinja is a common choice, and may be familiar to anyone who has played with Flask.

- In the machine-learning space, I'm constantly finding new things I might want to look out for, or new ways to compare models, or new ways to analyse a dataset - so both the content of a report and the features I can pack into any report should be flexible.

- A lot of the data I work with is in .csv format, so having tools to work with that and generate interrogatable HTML blocks from it would be neat.

Step One - Lay a foundation

For pretty much any size project bigger than tinkering in the command line for a couple of minutes, I'm fond of setting up a Github repo and a consistent environment.

This, I think, will be a pretty small-scale project, so I'm not terribly concerned with laying down a full project structure, but it's worth being comfortable with this for further reference.

This:

- Encourages good habits in keeping the project clean

- Helps me jump from my Mac laptop to my Linux desktop (or any other environment, for that matter) with a minimum of fuss

A few quick goals to start us off:

Set up a virtual environment

We want to create an isolated instance of Python for this project - or "virtual environment" - rather than using whatever general installation is present on this machine. This isolates our dependencies and makes it easier to move the project around. I'm working in Pycharm, which gives you the option to create new virtual environment from the start.

To make this transferable, I'll keep a requirements.txt file in the root of my project directory which details what packages are required in the environment.

There are many, many, many guides on this topic, and they're good to refer to for more specific details.

Set up a Git/Github repo

To implement version tracking and allow ready transport to and fro from Github, we'll initialise a Git repo locally (in the project folder) and create a new repo in Github. The local Git repo can then pushed to Github.

A succint guide can be found on Github.com.

As a matter of course of working in a Git/Github repo, we'll add the following to the root project directory:

- A

readme.mdfile that briefly describes the project, and - A

.gitignorefile that indicates which files and folders should not be tracked by Git and pushed to Github. This might include automatically generated files (from the IDE, or from the virtual environment, for instance), sensitive files and config data, or anything else you've created locally that doesn't need to be shared with the world. For me, this looks like:

# .gitignore

# Don't add the virtual environment, IDE, and Jupyter notebook info

venv

.idea

.ipynb_checkpoints

Write-up.ipynb

Github status

At this point, the skeleton of your project should look a bit like this.

Step Two - "Hello, World" templating

At this point, we have a very simple project structure that we can start populating with code and templates. To carry out a bit of a smoke-test and give me somewhere to build off of, I'd like to create the simplest possible report.

This first implementation should input no information, and output a simple "Hello, world!" HTML page.

A brief primer on templating

This project is built on the concept of templating and template processors. This is an enormous but very crucial field in web publishing.

In a crude explanation: we separate the structure of an HTML page and the content that is to be published. When it comes time to generate a new webpage (or in this context, a report!) we can input the content into a standardised structure and get a new webpage out.

Templating is well and truly ubiquitous now, but if you'd like an example of life without consistent manual or automatic templating, you can find many unironically charming examples in a Geocities archive.

Building 'hello, world' functionality

Building on this distinction between structure and content, we can create very simple examples for both to test the system.

Structure

Our structure, in this case, is a near-empty HTML page with locations for data to be input. We'll call this a "template", and we'll store this and others under a template folder in our root project directory. We'll create a new HTML file under this folder - {project_folder}/template/report.html. The contents of this file are as follows:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>{{ content }}</title>

</head>

<body>

{{ content }}

</body>

</html>

Note the elements here within curly braces (in this case double curly braces - {{ and }}). This is where dynamic content will be entered.

Template processors such as Jinja are very powerful and allow many features to be present in templates beyond simple insertion. Take a look at the first example on the Jinja homepage and see if you can make sense of it.

Content

Our content, for now, can be as simple as hello, world!.

We'll create a new file in the root of the project directory called {project_folder}/autoreporting.py and hardcode our 'content' to begin with.

content = "Hello, world!"

Functionality

We have structure and content - now we just need to get them combined using Jinja.

Firstly, create an outputs directory and add it to your .gitignore file. We'll dump what we create in this folder, but there's no reason to share whatever ends up in here in your repo.

Jinja requires an Environment object to store and define things like the config and loader - i.e. where we will pull our templates from. In this case, we're running off the local filesystem, so a FileSystemLoader specified to search in the templates directory will do us just fine.

With our env instance, we can render our basic template and write this to file.

Our autoreporting.py script now looks like this:

from jinja2 import FileSystemLoader, Environment

# Content to be published

content = "Hello, world!"

# Configure Jinja and ready the template

env = Environment(

loader=FileSystemLoader(searchpath="templates")

)

template = env.get_template("report.html")

def main():

"""

Entry point for the script.

Render a template and write it to file.

:return:

"""

with open("outputs/report.html", "w") as f:

f.write(template.render(content=content))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Note the argument to template.render, content=content. This links the template and our code. The first content refers to the {{ content }} in the template, while the second is the string defined in the script. We define this relationship and the string is fed into the template to make a substitution.

Results so far

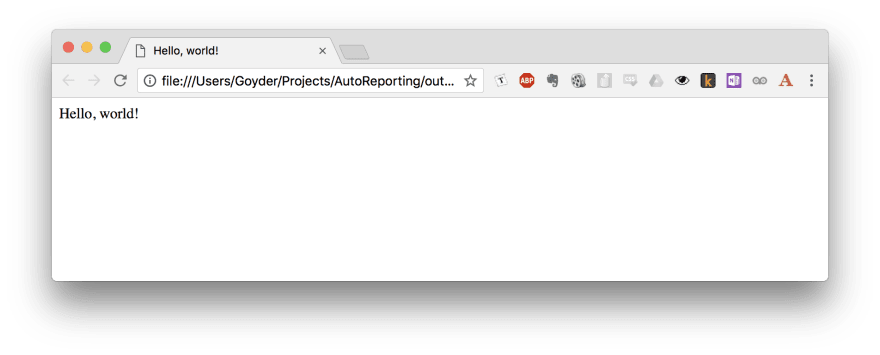

If you run this script and all goes well, a new report.html file will be written under outputs/. Open this file and behold what you have created!

This certainly meets the criteria of "very simple, but functional."

If you inspect the HTML of the page, you'll note that the {{ content }} tags in the template were neatly replaced by the Hello, world! string, which is the crux of this affair.

Github status

You've developed a new feature, so it's a good point to commit and push to Github.

Your repo should probably look a bit like this.

Next Steps

The reporter walks and works, but we certainly don't have any sort of meaningful input or flexibility at this point. Our next steps will be to explore how we can read in data and report on it, and start working with JavaScript and CSS.

Top comments (5)

Perfectly succinct advice.

Loved this post.

I find it applies to all problems, even those outside the technical realm.

This is a great guide! For generating the HTML bundle, you should check out the datapane framework - it lets you create HTML reports from DataFrames, plots, Markdown etc. I'm one of the people building it!

I've begun to learn python this week and your post is really useful for "applying" the recent gathered knowledge.

Thanks.

Glad I could help, Renan!