As a female programmer, the first time I heard about Margaret Hamilton, the woman behind the NASA software team that landed astronauts on the moon in 1969, I couldn’t help but feel inspired. Hamilton was a computer pioneer responsible for creating the most sophisticated computer system of its day.

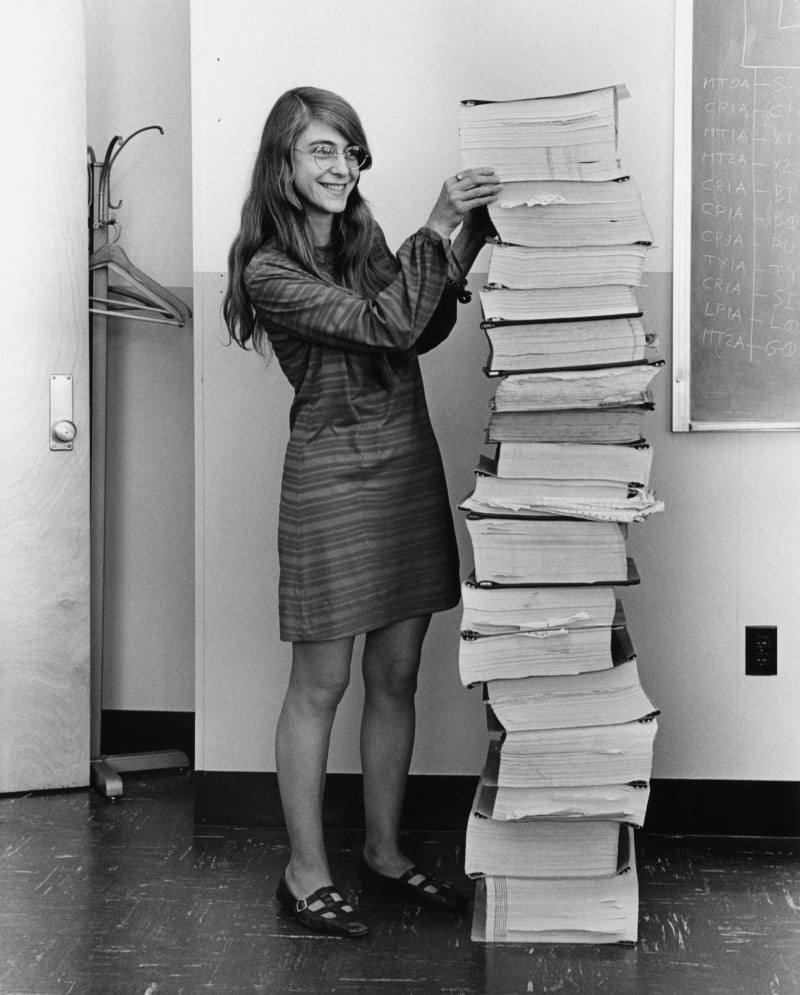

Margaret Hamilton standing next to the software her team produced for the Apollo project

Margaret Hamilton standing next to the software her team produced for the Apollo project

Her achievements were tremendous at a time when computer technology was in its infancy. Hamilton and her team literally used paper punch cards to feed information into huge computers with no screen interface. Each punch card consisted of up to ten rows, numbered 0 to 9, and 80 columns. Each column represented a single character (byte) in binary format, expressed as either a hole of no hole. Each card in its entirety represented a separate instruction for the computer. The overall memory of the Apollo Guidance Computer was equivalent to about 72 kilobytes of computer memory (your cell phone probably carries almost a million times that). The software had to be woven into the core “rope” memory by looping wires through and around a core to represent the ones and zeros of computer programs. This “rope” carried the software instructions which compensated for the Apollo computers’ limited memory.

Weaving the core ropes at a factory in Boston

Weaving the core ropes at a factory in Boston

One of the key components that made Hamilton’s program so special at the time was that she always sought to design Apollo’s software to be capable of dealing with unknown problems which remaining flexible enough to interrupt a task in order to prioritize another more important one. She even made the realization that sound could be used to serve as an error detector.

One story I found particularly interesting begins with the fact that she was a working mother and would often bring her daughter to work with her. One day her daughter was “playing astronaut” and pushed a simulator button that made the system crash. Hamilton realized that the same mistake could easily be made by an astronaut so she recommended adjusting the software to address it but she was assured that “astronauts are trained to never make a mistake.” Lo and behold, during Apollo 8’s moon-orbiting flight, astronaut Jim Lovell made the exact same error as Hamilton’s daughter. The button launched a program that wiped out all the navigation data Lovell had been collecting, which was the astronauts’ way of returning to earth. Hamilton and her team spent nine hours poring over the 8-inch thick program listing to find a solution. Luckily they were successful but for all future Apollo flights, protection was built into the software to make sure it never happened again. The lesson taught here is to view the whole mission as a system where “part is realized as software, part is peopleware, and part is hardware.”

Teasel Muir-Harmony, historian of science and technology and curator of the Apollo Spacecraft Collection, describes her impression of Hamilton perfectly. “What I think about when I think about Margaret Hamilton is her quote that 'there was no choice but to be pioneers,' because I think that really embodies who she was and her significance in this program. She was a pioneer when it came to development of software engineering and. . . . a pioneer as a woman in the workplace contributing to this type of program, taking on this type of role.”

Thanks to Hamilton and her historical work, software engineering, a concept Hamilton pioneered, has found its way to nearly every human undertaking. As President Barack Obama put it as he awarded her with the Medal of Freedom, “her example speaks of the American spirit of discovery that exists in every little girl and little boy who knows that somehow to look beyond the heavens is to look deep within ourselves.”

Top comments (0)