Init container can be converted to sidecar container using

restartpolicy: always

Example of a Sidecar Container

# This is the identity the Pods will run as.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

namespace: default

---

# This defines the namespace-scope permissions granted.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

namespace: default

rules:

- apiGroups:

- ''

resources:

- pods

verbs:

- get

- watch

---

# This joins the ServiceAccount to the Role above.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

namespace: default

roleRef:

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

kind: Role

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

---

# This defines the cluster-scope permissions granted.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterRole

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

rules:

- apiGroups:

- ''

resources:

- nodes

verbs:

- get

- watch

---

# This joins the ServiceAccount to the ClusterRole above.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterRoleBinding

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

roleRef:

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

kind: ClusterRole

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

namespace: default

---

# This is the actual workload.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: demo-kubectl-sidecar

namespace: default

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: demo-kubectl-sidecar

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: demo-kubectl-sidecar

spec:

serviceAccountName: demo-kubectl-sidecar

securityContext:

# Set this to any valid GID, and two things happen:

# 1) The volume "content" is group-owned by this GID.

# 2) This GID is added to each container.

fsGroup: 9376

containers:

- name: server

image: nginx

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /usr/share/nginx/html

name: content

readOnly: true

initContainers:

- name: sidecar

image: thockin/kubectl-sidecar:v1.30.0-1

restartPolicy: Always

env:

- name: MYPOD

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.name

- name: MYNS

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.namespace

- name: MYNODE

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: spec.nodeName

args:

- bash

- -c

- |

while true; do

kubectl -n $MYNS get pod $MYPOD -o json | jq '.status' > /data/this-pod-status.json

kubectl get node $MYNODE -o json | jq '.status' > /data/this-node-status.json

sleep 30

done

volumeMounts:

- name: content

mountPath: /data

securityContext:

# This doesn't need to run as root.

runAsUser: 9376

runAsGroup: 9376

volumes:

- name: content

emptyDir: {}

terminationGracePeriodSeconds: 5

kubectl apply -f <yaml-file-name>

kubectl port-forward deployment/demo-kubectl-sidecar 8080:80

curl http://localhost:8080/this-pod-status.json

curl http://localhost:8080/this-node-status.json

Understanding the Role of the Pause Container in Kubernetes

When we try to restart a container then its IP changes. But if a container inside a pod restart then the IP of the pod remains same, this is due to pause container present in kubernetes.

It holds the network namespace and IP address for the Pod, allowing the other containers within the Pod to communicate and share networking resources.

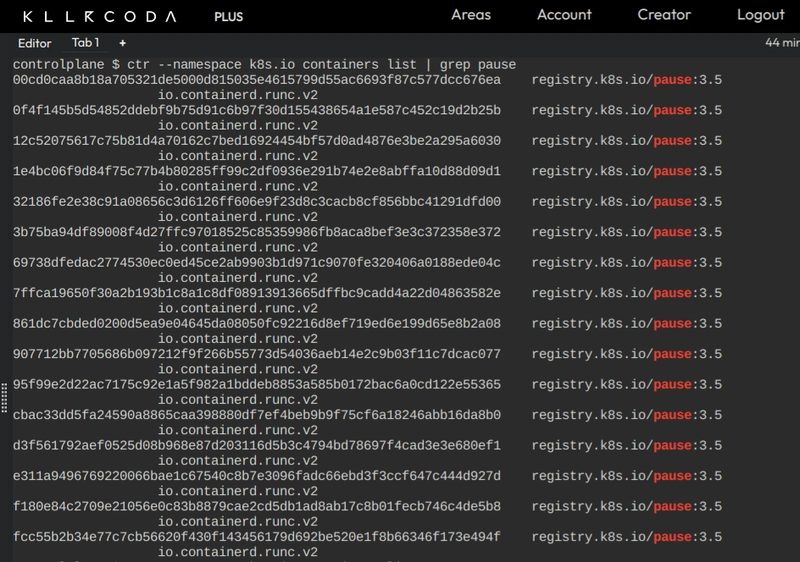

The pause container is automatically created by containerd when you start a Pod. It is not visible to kubectl, but you can see it using the ctr command.

How to View Pause Containers and Pod IPs

-

To see all

pause containerson the node

ctr --namespace k8s.io containers list | grep pause -

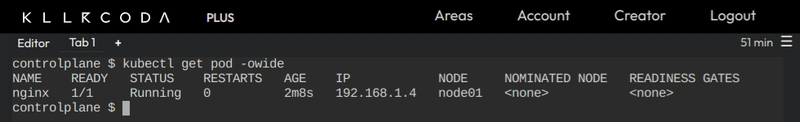

To check the

IPof the specific pod

kubectl get pod <pod-name> -owide

Kubernetes User Namespaces

User namespaces enhance security by isolating user IDs (UIDs) and group IDs (GIDs) inside containers from the host system. This means that a root user inside a container doesn't have root privileges on the host, reducing the risk if a container is compromised.

This feature helps limit the damage from attacks by keeping container permissions separate from host permissions. User namespaces are now more stable and widely available, supporting both stateless and stateful pods.

Pod Disruptions

Pods do not disappear until someone (a person or a controller) destroys them, or there is an unavoidable hardware or system software error.

Types: *Voluntary and involuntary disruptions*

- Voluntary disruption

* Deleting the deployment

* Updating a deployment's pod template

* Directly deleting a pod

* Draining a node

* Removing a pod from a node to allow something else to fit on that node

- Non-voluntary disruption

* Hardware failure

* Cluster administrator deletes a VM (instance) by mistake

* Cloud provider or hypervisor failure makes a VM disappear

* Kernel panic

* Node disappears from the cluster due to network partition

* Eviction of a pod due to the node running out of resources

Here are some ways to reduce involuntary disruptions:

Ensure your pod requests the resources it needs.

Replicate your application if you need higher availability.

For even higher availability with replicated applications, spread them across racks (using anti-affinity) or across zones (if using a multi-zone cluster).

Pod disruption budgets (PDB)

It helps to keep your application running smoothly by limiting how many pods can be disrupted at once. They ensure that a minimum number of pods remain available during maintenance or updates. You set up a PDB to specify how many pods need to stay up and running, and Kubernetes follows these rules during planned disruptions but not during unexpected ones like crashes.

We use PDB only for high availability

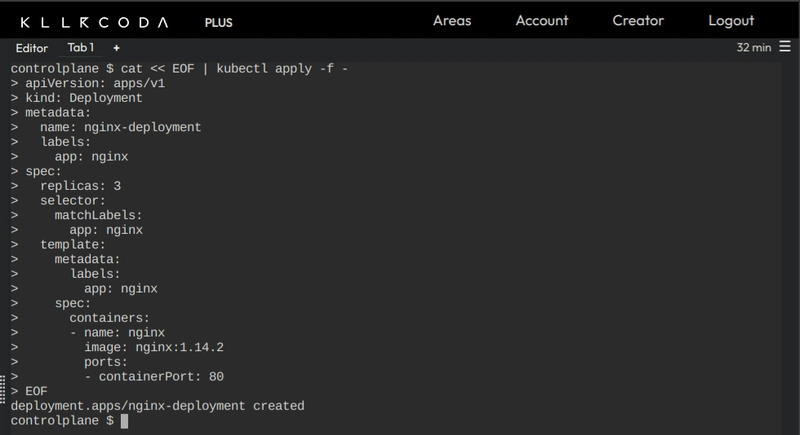

Here is an example of a PDB configuration:

-

Create a deployment

apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: Deployment metadata: name: nginx-deployment labels: app: nginx spec: replicas: 3 selector: matchLabels: app: nginx template: metadata: labels: app: nginx spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx:1.14.2 ports: - containerPort: 80 -

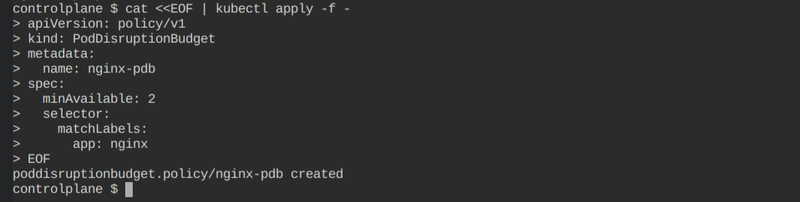

Create PDB

apiVersion: policy/v1 kind: PodDisruptionBudget metadata: name: nginx-pdb spec: minAvailable: 2 selector: matchLabels: app: nginx -

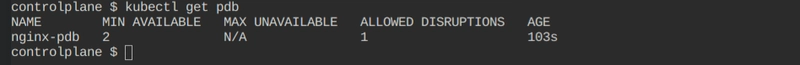

Check available PDB

kubectl get pdb -

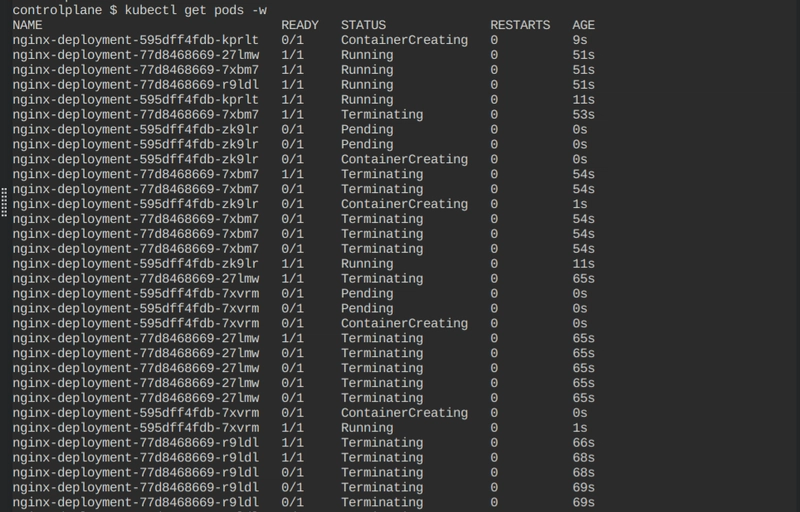

Do rolling updates (update nginx image)

kubectl set image deployment/nginx-deployment nginx=nginx:1.16.1 -

Watch the pods now

kubectl get pods -w

Setting Resource Requests and Limits for Efficient Resource Management

In Kubernetes, applications run as pods inside nodes. A node is a physical or virtual machine with specific configurations like CPU and memory. Each application consumes a certain amount of these resources.

Kubernetes uses the concepts of resource requests and limits to manage CPU and memory usage:

Resource Requests: The minimum amount of CPU and memory that a pod needs to run.

Resource Limits: The maximum amount of CPU and memory a pod is allowed to use.

These settings are crucial for scheduling because they help the scheduler find the best node to deploy a pod. For example, if a pod requires at least 2 CPUs and 1 GB of RAM, you set these values in the resource requests and limits. The scheduler then finds a suitable node that can accommodate these requirements.

When creating a highly available Kubernetes cluster, it's important to properly configure resource requests and limits to ensure efficient resource utilization and stability.

Understanding CPU Throttling in Kubernetes

CPU throttling means limiting a pod's CPU usage when it tries to use more than its allowed amount. This prevents one pod from using too much CPU and affecting other pods on the same node. If a pod reaches its CPU limit, Kubernetes slows it down to stay within the limit, which can make the pod run slower. This helps ensure that resources are shared fairly and the cluster stays stable.

Overutilization and Underutilization of Resources

Overutilization happens when a resource is used too much, exceeding its capacity. For example, if a CPU is consistently running at 100%, it can cause performance issues, slow down processes, or even crash the system because there's not enough capacity left for other tasks.

Underutilization occurs when a resource is used too little, meaning it's not being fully used even though it's available. For instance, if a server has a lot of memory but is only using a small portion of it, the rest of the memory is underutilized, leading to inefficient use of resources and potentially higher costs without any benefit.

we can specify the LimitRange of a namespace

apiVersion: v1

kind: LimitRange

metadata:

name: example-limitrange

namespace: default

spec:

limits:

- type: Pod

max:

cpu: "2"

memory: "1Gi"

min:

cpu: "200m"

memory: "100Mi"

- type: Container

max:

cpu: "1"

memory: "500Mi"

min:

cpu: "100m"

memory: "50Mi"

default:

cpu: "300m"

memory: "200Mi"

defaultRequest:

cpu: "200m"

memory: "100Mi"

Now you can directly create pods without specifying limit and ranges it will automatically assigned to the pod

Quality of Service (QoS)

Quality of Service (QoS) in Kubernetes is a way to prioritize and manage resources for Pods to ensure they get the resources they need based on their importance and requirements. Kubernetes classifies Pods into different QoS tiers based on their resource requests and limits.

-

Pods that have both CPU and memory requests and limits set, and the requests are equal to the limits. These Pods get the highest priority for resources and known as

guaranteedQOS.Guaranteed QoS Example:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-guaranteed spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx resources: requests: memory: "256Mi" cpu: "500m" limits: memory: "256Mi" cpu: "500m"

-

Pods that have CPU and memory requests and limits set, but the requests and limits are not equal. These Pods get some level of resource assurance but can use more resources if available and known as

burstableQOS.Burstable QoS Example:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-burstable spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginx resources: requests: memory: "256Mi" limits: memory: "512Mi"

-

Pods that do not specify any CPU or memory requests or limits. These Pods get the lowest priority for resources and can be easily evicted if the node is under resource pressure and known as

besteffortQOS.BestEffort QoS Example:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: nginx-besteffort spec: containers: - name: nginx image: nginxWhen k8s runs out of resource then on the basis of QOS class, first evict the

BestEffortthenBurstableand at lastGuaranteedevicted

Understanding Kubernetes Downward API

Downward API is a useful feature that allows Pods to access information about themselves and the cluster environment. It helps applications running inside Pods to get metadata and resource details, which they might need to operate correctly or adjust their behavior.

The Downward API provides a way for Pods to obtain information about themselves, such as:

Pod Name: The name assigned to the Pod.

Namespace: The namespace in which the Pod is running.

Pod Labels and Annotations: Metadata attached to the Pod.

Resource Limits and Requests: Information about how much CPU and memory the Pod has been allocated.

How to Use the Downward API

The Downward API provides this information through environment variables or files within the Pod. Here’s a simple example of how to use it:

-

Using Environment Variables:

You can define environment variables in your Pod spec to expose metadata from the Downward API:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: my-pod spec: containers: - name: my-container image: my-image env: - name: POD_NAME valueFrom: fieldRef: fieldPath: metadata.name - name: POD_NAMESPACE valueFrom: fieldRef: fieldPath: metadata.namespaceIn this example:

* The `POD_NAME` environment variable will be set to the Pod's name.

* The `POD_NAMESPACE` environment variable will be set to the Pod's namespace.

-

Using Volumes:

You can also expose metadata through files in a volume:

apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: my-pod spec: containers: - name: my-container image: my-image volumeMounts: - name: pod-info mountPath: /etc/podinfo volumes: - name: pod-info downwardAPI: items: - path: "name" fieldRef: fieldPath: metadata.name - path: "namespace" fieldRef: fieldPath: metadata.namespaceIn this example:

* The Pod’s name and namespace will be available as files in /etc/podinfo within the container.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article delves into essential Kubernetes concepts, including the transformation of init containers to sidecar containers, the critical role of the pause container in maintaining network namespaces, and the security benefits of user namespaces. It also covers the different types of pod disruptions and how to manage them using Pod Disruption Budgets (PDB). Additionally, the article explains the importance of setting resource requests and limits for efficient resource utilization and stability, and it categorizes the different Quality of Service (QoS) classes in Kubernetes. Practical examples and YAML configurations are provided to help illustrate these concepts, making it a comprehensive guide for managing Kubernetes environments effectively.

Top comments (0)