If you haven't deployed a lot of Django apps, then you might wonder: how do professionals put Django apps on the internet? What does Django typically look like when it's running in production? You might even be thinking what the hell is production?

Before I started working a developer there was just a fuzzy cloud in my head where the knowledge of production infrastructure should be. If there's a fuzzy cloud in your head, let's fix it. There are many ways to extend a Django server setup to achieve better performance, cost-effectiveness and reliability. This post will take you on a tour of some common Django server setups, from the most simple and basic to the more complex and powerful. I hope it will build up your mental model of how Django is hosted in production, piece-by-piece.

Your local machine

Let's start by reviewing a Django setup that you are alreay familiar with: your local machine. Going over this will be a warm-up for later sections. When you run Django locally, you have:

- Your web browser (Chrome, Safari, Firefox, etc)

- Django running with the runserver management command

- A SQLite database sitting in your project folder

Pretty simple right? Next let's look at something similar, but deployed to a web server.

Simplest possible webserver

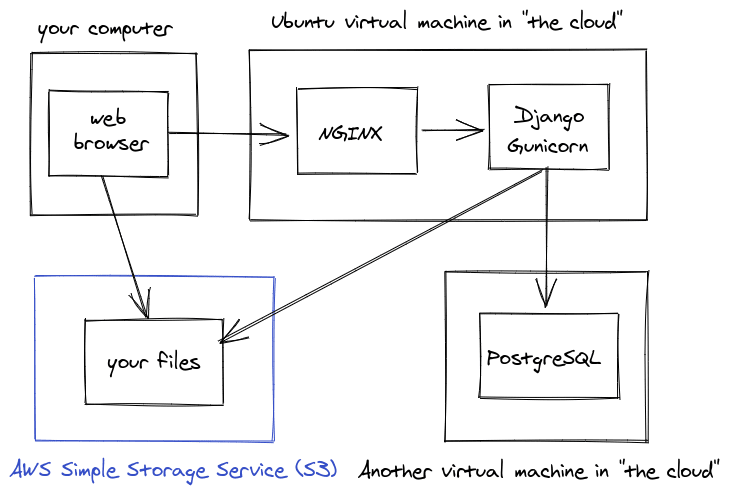

The simplest Django web server you can setup is very similar to your local dev environment. Most professional Django devs don't use a basic setup like this for their production environments. It works perfectly fine, but it has some limitations that we'll discuss later. It looks like this:

Typically people run Django on a Linux virtual machine, often using the Ubuntu distribution. The virtual machine is hosted by a cloud provider like Amazon, Google, Azure, DigitalOcean or Linode.

Instead of using runserver, you should use a WSGI server like Gunicorn to run your Django app. I go into more detail on why you shouldn't use runserver in production, and explain WSGI here. Otherwise, not that much is different from your local machine: you can still use SQLite as the database (more here).

This is the bare bones of the setup. There are a few other details that you'll need to manage like setting up DNS, virtual environments, babysitting Gunicorn with a process supervisor like Supervisord or how to serve static files with Whitenoise. If you're interested in a more complete guide on how to set up a simple server like this, I wrote a guide that explains how to deploy Django.

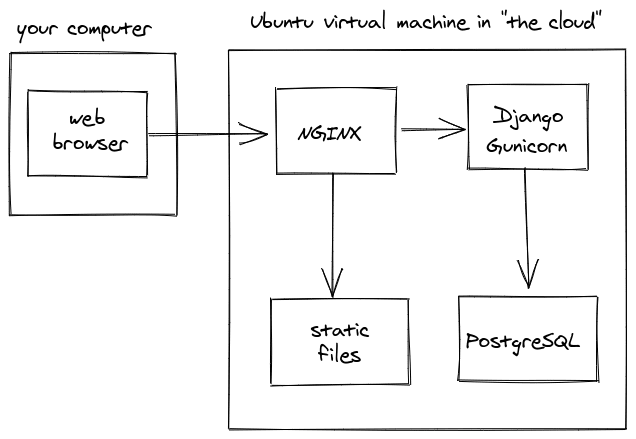

Typical standalone webserver

Let's go over an environment that a professional Django dev might set up in production when using a single server. It's not the exact setup that everyone will always use, but the structure is very common.

Some things are the same as the simple setup above: it's still a Linux virtual machine with Django being run by Gunicorn. There are three main differences:

- SQLite has been replaced by a different database, PostgreSQL

- A NGINX web server is now sitting in-front of Gunicorn in a reverse-proxy setup

- Static files are now being served from outside of Django

Why did we swap SQLite for PostgreSQL? In general Postgres is a litte more advanced and full featured. For example, Postgres can handle multiple writes at the same time, while SQLite can't.

Why did we add NGINX to our setup? NGINX is a dedicated webserver which provides extra features and performance improvements over just using Gunicorn to serve web requests. For example we can use NGINX to directly serve our app's static and media files more efficiently. NGINX can also be configured to a lot of other useful things, like encrypt your web traffic using HTTPS and compress your files to make your site faster. NGINX is the web server that is most commonly combined with Django, but there are also alternatives like the Apache HTTP server and Traefik.

It's important to note that everything here lives on a single server, which means that if the server goes away, so does all your data, unless you have backups. This data includes your Django tables, which are stored in Postgres, and files uploaded by users, which will be stored in the MEDIA_ROOT folder, somewhere on your filesystem. Having only one server also means that if your server restarts or shuts off, so does your website. This is OK for smaller projects, but it's not acceptable for big sites like StackOverflow or Instagram, where the cost of downtime is very high.

Single webserver with multiple apps

Once you start using NGINX and PostgreSQL, you can run multiple Django apps on the same machine. You can save money on hosting fees by packing multiple apps onto a single server rather than paying for a separate server for each app. This setup also allows you to re-use some of the services and configurations that you've already set up.

NGINX is able to route incoming HTTP requests to different apps based on the domain name, and Postgres can host multiple databases on a single machine.

For example, I use a single server to host some of my personal Django projects: Matt's Links, Memories Ninja and Blog Reader

I've omitted the static files for simplicity. Note that having multiple apps on one server saves you hosting costs, but there are downsides: restarting the server restarts all of your apps.

Single webserver with a worker

Some web apps need to do things other than just CRUD. For example, my website Blog Reader needs to scrape text from a website and then send it to an Amazon API to be translated into audio files. Another common example is "thumbnailing", where you upload a huge 5MB image file to Facebook and they downsize it into a crappy 120kB JPEG. These kinds of tasks do not happen inside a Django view, because they take too long to run. Instead they have to happen "offline", in a separate worker process, using tools like Celery, Huey, Django-RQ or Django-Q. All these tools provide you with a way to run tasks outside of Django views and do more complicated things, like co-ordinate multiple tasks and run them on schedules.

All of these tools follow a similar pattern: tasks are dispatched by Django and put in a queue where they wait to be executed. This queue is managed by a service called a "broker", which keeps track of all the tasks that need to be done. Common brokers for Django tasks are Redis and RabbitMQ. A worker process, which uses the same codebase as your Django app, pulls tasks out the broker and runs them.

If you haven't worked with task queues before then it's not immediately obvious how this all works, so let me give an example. You want to upload a 2MB photo of your breakfast from your phone to a Django site. To optimise image loading performance, the Django site will turn that 2MB photo upload into a 70kB display image and a smaller thumbnail image. So this is what happenes:

- A user uploads a photo to a Django view, which saves the original photo to the filesystem and updates the database to show that the file has been received

- The view also pushes a thumbnailing task to the task broker

- The broker receives the task and puts it in a queue, where it waits to be executed

- The worker asks the broker for the next task and the broker sends the thumbnailing tasks

- The worker reads the task description and runs some Python function, which reads the original image from the filesystem, creates the smaller thumbnail images, saves them and then updates the database to show that the thumbnailing is complete

If you want to learn more about this stuff, I've written guides for getting started with offline tasks and scheduled tasks with Django Q.

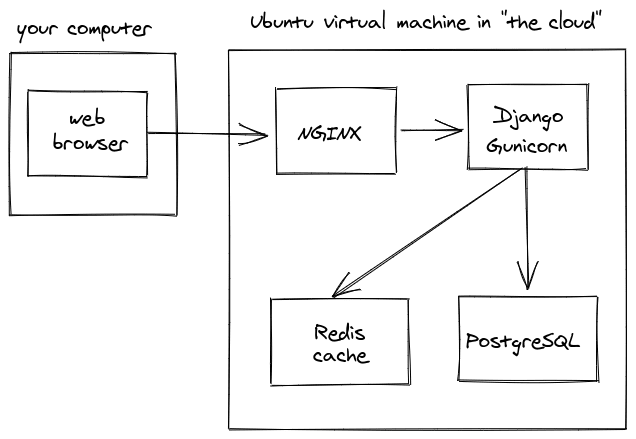

Single webserver with a cache

Sometimes you'll want to use a cache to store data for a short time. For example, caches are commonly used when you have some data that was expensive to pull from the database or an API and you want to re-use it for a little while. Redis and Memcached are both popular cache services that are used in production with Django. It's not a very complicated setup.

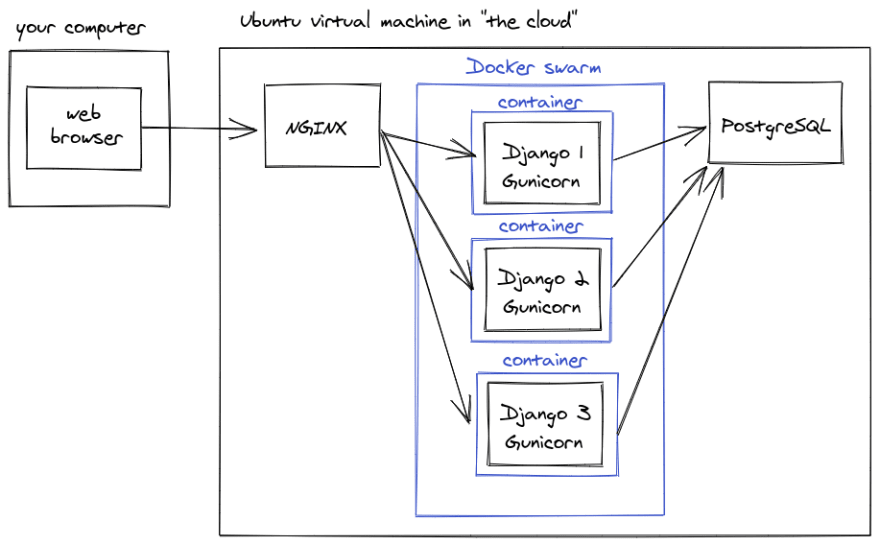

Single webserver with Docker

If you've heard of Docker before you might be wondering where it factors into these setups. It's a great tool for creating consistent programming environments, but it doesn't actually change how any of this works too much. Most of the setups I've described would work basically the same way... except everything is inside a Docker container.

For example, if you were running multiple Django apps on one server and you wanted to use Docker containers, then you might do something like this using Docker Swarm:

As you can see it's not such a different structure compared to what we were doing before Docker. The containers are just wrappers around the services that we were already running. Putting things inside of Docker containers doesn't really change how all the services talk to each other. If you really wanted to you could wrap Docker containers around more things like NGINX, the database, a Redis cache, whatever. This is why I think it's valuable to learn how to deploy Django without Docker first. That said, you can do some more complicated setups with Docker containers, which we'll get into later.

External services

So far I've been showing you server setups with just one virtual machine running Ubuntu. This is the simplest setup that you can use, but it has limitations: there are some things that you might need that a single server can't give you. In this section I'm going to walk you through how we can break apart our single server into more advanced setups.

If you've studied programming you might have read about separation of concerns, the single responsibility principle and model-view-controller (MVC). A lot of the changes that we're going to make will have a similar kind of vibe: we're going to split up our services into smaller, more specialised units, based on their "responsibilities". We're going to pull apart our services bit-by-bit until there's nothing left. Just a note: you might not need to do this for your services, this is just an overview of what you could do.

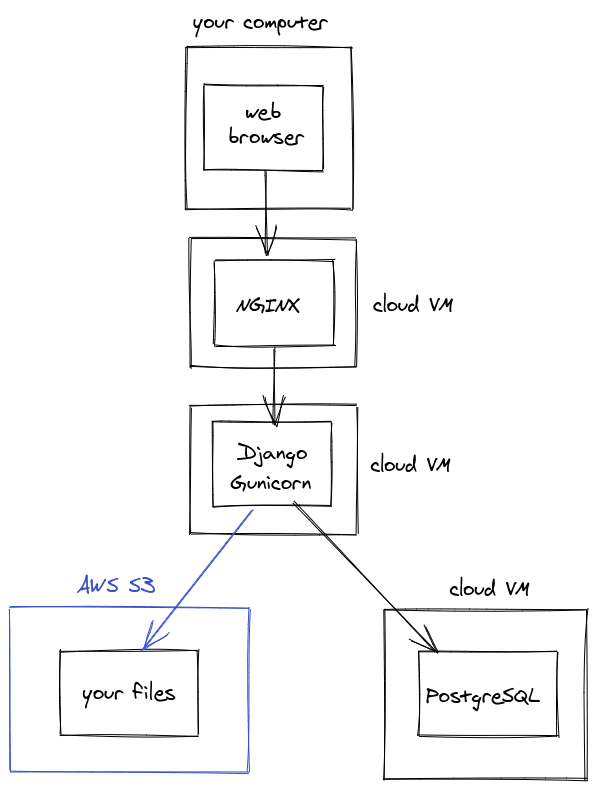

External services - database

The first thing you'd want to pull off of our server is the database. This involves putting PostgreSQL onto its own virtual machine. You can set this up yourself or pay a little extra for an off-the-shelf service like Amazon RDS.

There are a couple of reasons that you'd want to put the database on its own server:

- You might have multiple apps on different servers that depend on the same database

- Your database performance will not be impacted by "noisy neighbours" eating up CPU, RAM or disk space on the same machine

- You've moved your precious database away from your Django web server, which means you can delete and re-create your Django app's server with less concern

- mumble muble security mumble

Using an off-the-shelf option like AWS RDS is attractive because it reduces the amount of admin work that you need to run your database server. If you're a backend web developer with a lot of work to do and more money than time then this is a good move.

External services - object storage

It is common to push file storage off the web server into "object storage", which is basically a filesystem behind a nice API. This is often done using django-storages, which I enjoy using. Object storage is usually used for user-uploaded "media" such as documents, photos and videos. I use AWS S3 (Simple Storage Service) for this, but every big cloud hosting provider has some sort of "object storage" offering.

There are a few reasons why this is a good idea

- You've moved all of your app's state (files, database) off of your server, so now you can move, destroy and re-create the Django server with no data loss

- File downloads hit the object storage service, rather than your server, meaning you can scale your file downloads more easily

- You don't need to worry about any filesystem admin, like running out of disk space

- Multiple servers can easily share the same set of files

Hopefully you see a theme here, we're taking shit we don't care about and making it someone else's problem. Paying someone else to do the work of managing our files and database leaves us more free time to work on more important things.

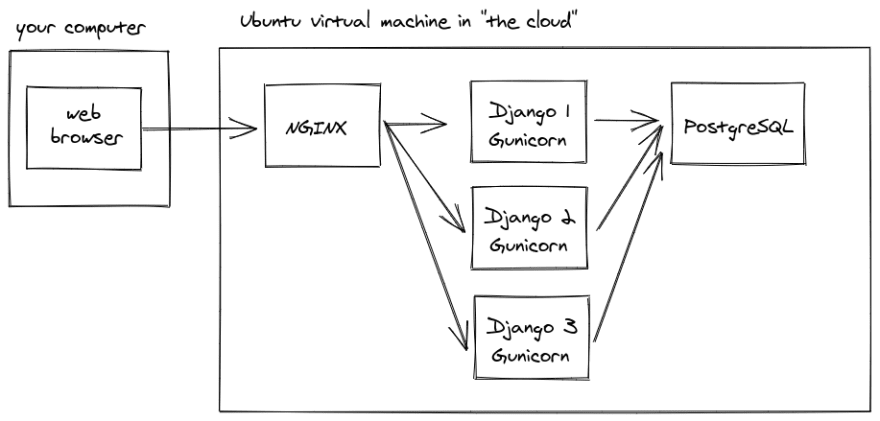

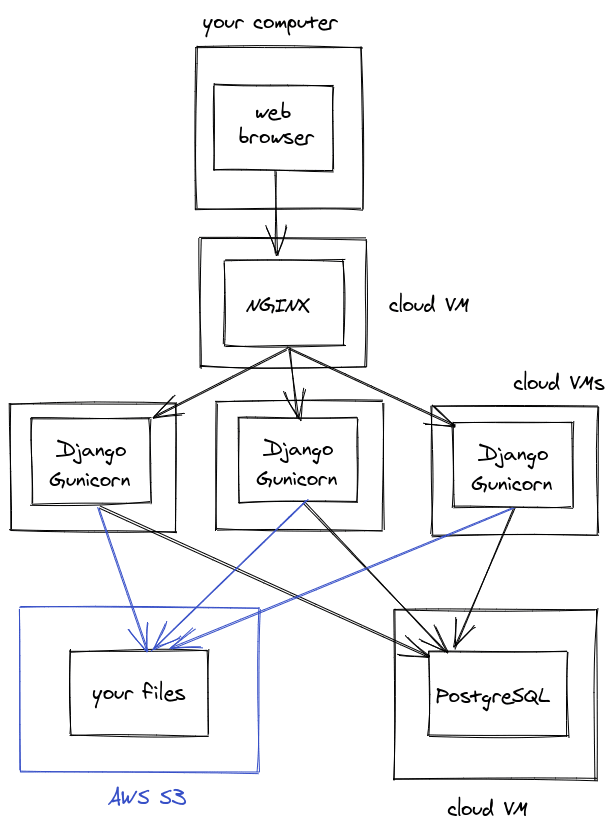

External services - web server

You can also run your "web server" (NGINX) on a different virtual machine to your "app server" (Gunicorn + Django):

This seems kind of pointless though, why would you bother? Well, for one, you might have multiple identical app servers set up for redundancy and to handle high traffic, and NGINX can act as a load balancer between the different servers.

You could also replace NGINX with an off-the-shelf load balancer like an AWS Elastic Load Balancer or something similar.

Note how putting our services on their own servers allows us to scale them out over multiple virtual machines. We couldn't run our Django app on three servers at the same time if we also had three copies of our filesystem and three databases.

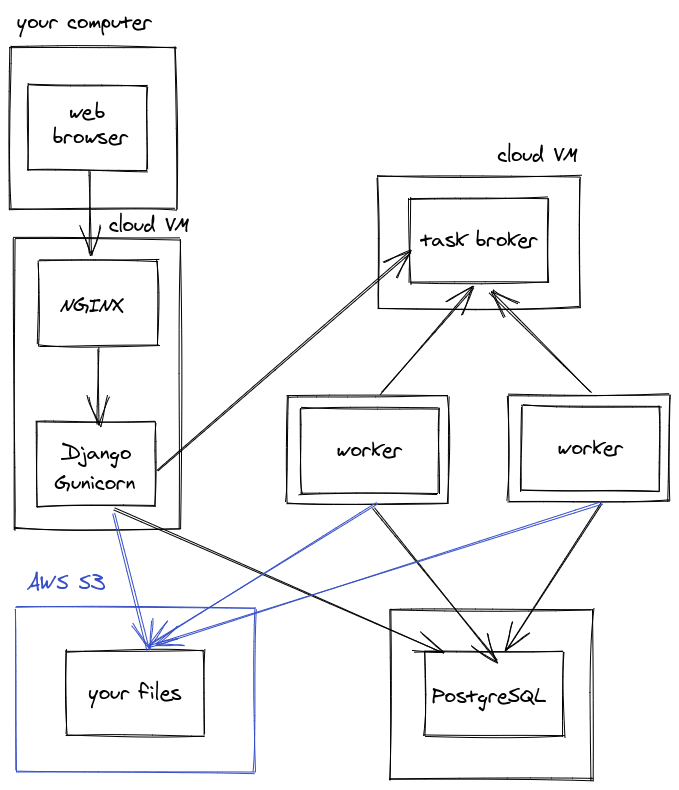

External services - task queue

You can also push your "offline task" services onto their own servers. Typically the broker service would get its own machine and the worker would live on another:

Splitting your worker onto its own server is useful because:

- You can protect your Django web app from "noisy neighbours": workers which are hogging all the RAM and CPU

- You can give the worker server extra resources that it needs: CPU, RAM, or access to a GPU

- You can now make changes to the worker server without risking damage to the task queue or the web server

Now that you've split things up, you can also scale out your workers to run more tasks in parallel:

You could potentially swap our your self-managed broker (Redis or RabbitMQ) for a managed queue like Amazon SQS.

External services - final form

If you went totally all-out, your Django app could be set up like this:

As you can see, you can go pretty crazy splitting up all the parts of your Django app and spreading across multiple servers. There are many upsides to this, but the downside is that you now have mutiple servers to provision, update, monitor and maintain. Sometimes the extra complexity is well worth or and sometimes it's a waste of your time. That said, there are many benefits to this setup:

- Your web and worker servers are completely replaceable, you can destroy, create and update them without affecting uptime at all

- You can now do blue-green deployments with zero web app downtime

- Your files and database are easily shared between multiple servers and applications

- You can provision different sized servers for their different workloads

- You can swap out your self-managed servers for managed infrastructure, like moving your task broker to AWS SQS, or your database to AWS RDS

- You can now autoscale your servers (more on this later)

When you have complicated infrastructure like this you need to start automating your infrastructure setup and server config. It's just not feasible to manage this stuff manually once your setup has this many moving parts. I recorded a talk on configuration management that introduces these concepts. You'll need to start looking into tools like Ansible and Packer to configure your virtual machines, and tools like Terraform or CloudFormation to configure your cloud services.

Auto scaling groups

You've already seen how you can have multiple web servers running the same app, or multiple worker servers all pulling tasks from a queue. These servers cost money, dollars per hour, and it can get very expensive to run more servers than you need.

This is where autoscaling comes in. You can setup your cloud services to use some sort of trigger, such as virtual machine CPU usage, to automatically create new virtual machines from an image and add them to an autoscaling group.

Let's use our task worker servers as an example. If you have a thumbnailing service that turns big uploaded photos into smaller photos then one server should be able to handle dozens of file uploads per second. What if during some periods of the day, like around 6pm after work, you saw file uploads spike from dozens per second to thousands per second? Then you'd need more servers! With an autoscaling setup, the CPU usage on your worker servers would spike, triggering the creation of more and more worker servers, until you had enough to handle all the uploads. When the rate of file uploads drops, the extra servers would be automatically destroyed, so you aren't always paying for them.

Container clusterfuck

There is a whole world of container fuckery that I haven't covered in much detail, because:

- I don't know it very well

- It's a little complicated for the targed audience of this post; and

- I don't think that most people need it

For completeness I'll quickly go over some of the cool, crazy things you can do with containers. You can use tools like Kubernetes and Docker Swarm with a set of config files to define all your services as Docker containers and how they should all talk to each other. All your containers run somewhere in your Kubernetes/Swarm cluster, but as a developer, you don't really care what server they're on. You just build your Docker containers, write your config file, and push it up to your infrastructure.

Using these "container orchestration" tools allows you to decouple your containers from their underlying infrastructure. Multiple teams can deploy their apps to the same set of servers without any conflict between their apps.

This is the kind of infrastructure that enables teams to deploy microservices. Big enterprises like Target will have specialised teams dedicated to setting up and maintaining these container orchestration systems, while other teams can use them without having to think about the underlying servers. These teams are essentially supplying a "platform as a service" (PaaS) to the rest of the organisation.

As you might have noticed, there is probably too much complexity in these container orchestration tools for them to be worth your while as a solo developer or even as a small team. If you're interested in this sort of thing you might like Dokku, which claims to be "the smallest PaaS implementation you've ever seen".

End of tour

That's basically everything that I know that I know about how Django can be set up in production. If you're interested in building up your infrastructure skills, then I recommend you try out one of the setups or tools that I've mentioned in this post. Hopefully I've built up your mental models of how Django gets deployed so that the next time someone mentions "task broker" or "autoscaling", you have some idea of what they're talking about.

If you enjoyed reading this you might also like other things I've written about deploying Django as simply as possible, how to get started with offline tasks, how to start logging to files and tracking errors in prod and my introduction to configuration management.

If you liked the box diagrams in this post check out Exalidraw.

Top comments (1)

sir this project memories ninja is amazing!! i want to make same, replicate this project!

do u have github by chance for this project?