As a web developer it is presumably beneficial to have a basic understanding of how the internet works! This isn't something I've known a great deal about, I've always just taken it for granted so I've decided to write some posts to further my own understanding; I thought IP addresses would be a good place to start. As always you can reach me on Twitter if you see any innacuracies or think that I have missed anything which should be included.

Every device which is connected to the internet needs an IP address. IP stands for Internet Protocol which is the set of rules that devices need to adhere to if they are going to be able to communicate with one another over the internet. When you visit a website with your web browser you are actually navigating to an IP address; fortunately for us there is a system in place which means that we don't have to remember the IP addresses of all of the websites we visit.

The Domain Name System

When you type a web address into a browser it is first translated into an IP address by the Domain Name System (DNS) which is a decentralised network of nameservers. There are four steps to a DNS query, they are:

- DNS Recursors - The "Recursive Resolver" acts as a middleman between the client (web browser) and Domain Name System. It holds a cache of previously resolved queries; if the requested domain name is in the cache then the IP address can be resolved straight away, if it is not in its cache then it requests data from the following three nameservers, starting with the Root Nameserver.

- Root Nameserver - The Root Nameserver will point the resolver to a relevant Top Level Domain (TLD) nameserver which maintains information on the requested domain extension (this is the .com, .co.uk, .org part of the URL).

- TLD Nameserver - The TLD Nameserver holds the location of all of the authoritative nameservers which have information on websites in their top-level domain, ie. .com.

- Authoritative Nameserver - Finally the resolver has the location of the Authoritative Nameserver and can request the IP address of the web address typed into the browser.

So you can see that DNS works by systematically narrowing down its search like searching for a tin of paint in an industrial estate; first you find B&Q, then you find the paint aisle, then you find the tin of paint on the shelves.

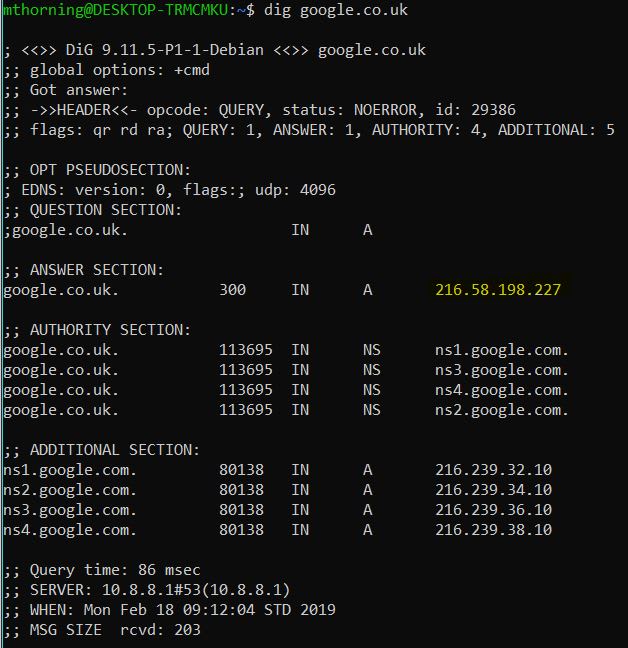

It is possible to interrogate a DNS nameserver using the Linux utility dig which will tell us the IP address of the domain and also the authoritative nameservers which provided the IP address.

Understanding the address

The most commonly used version of IP address is IPv4. This uses 32 bit addresses (4 bytes) which limits the total number of IP addresses to 232 (approximately 4.3 billion) addresses. This seems like a lot of IP addresses but when you consider the current global population is about 7.7 billion you realise it is probably not going to be enough! Fortunately, not all devices need to be directly connected to the internet as will be explained in a minute and there is a new version of Internet Protocol (IPv6) which is 128 bits resulting in 2128 or 340 undecillion (340 billion billion billion billion!) addresses.

IPv4 addresses are written using dotted decimal notation. There are 4 sections separated by a dot, each section is 1 byte (8 bits). In decimal, the maximum number you can reach is 255 which is 11111111 in binary.

IPv6 addresses still use dot notation but instead of decimal numbers they use hexadecimal, and instead of 8 bits per section they use 16. For comparison this means that the decimal equivalent maximum number for each dot-separated section is 65535 versus IPv4's 255. In addition to this, IPv6 uses 8 of these dot-separated sections instead IPv4's meager 4! Here's an example of an IPv6 address:

2001:0db8:0000:0000:0000:ff00:0042:8329

For convenience one or more leading zeros from a section may be removed and consecutive sections of zeros replaced with a double colon (only once per address) making our above example look like this:

2001:db8::ff00:42:8329

Not exactly memorable, I'm glad we've got DNS!

The aim of IPv6 is that every device will be able to be assigned its own unique address without any risk of exhausting the pool of addresses like is happening with IPv4.

How are we still using IPv4?

The IPv4 address exhaustion issue should have meant we ran out of IPv4 addresses a long time ago. In fact it has been anticipated since the 1980's! One of the main reasons we are still able to use IPv4 is because of private IP addresses. Like me, you probably have a lot of devices in your home which are connected to a wireless router. This is your access point to the internet and is therefore the only device in your home which needs a public IP. When a device is connected to a router, Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) assigns it a private IP address. These addresses are only unique within your Local Area Network (LAN) and will probably look like either 192.168.xxx.xxx or 10.xxx.xxx.xxx. When one of your devices makes a request the router replaces the private IP in the header with the public IP and records the sending device's details in a table. When the packet returns, the router looks up the saved reference in the table and forwards the packet on to the correct private IP address. The protocol which handles this is called Network Address Translation (NAT).

Ports

Another important subject related to IP adresses that I think we should touch upon is ports. Ports allow our devices to listen for many different services on the same IP address. A good way to think about how IP addresses, ports and NAT interact is with the following analogy.

I work in a building which rents offices to many different businesses. When I order a new gadget from Amazon, the postman delivers it to the reception of our building. The receptionist puts my parcel in a box with all the other parcels for my company which are then picked up by a colleague of mine who works for our company. My colleague knows which desk I work at and kindly delivers my parcel to me.

The address on my parcel contains the street address of the building I work in and the name of the company I work for. In this analogy the street address is the IP address and the company name is the port number. Notice there is nothing on the parcel to indicate which desk I work at, that information is held internally, by the kind person who brings my parcel to my desk (NAT).

There are many common port numbers (80 is HTTP, 22 is SSH, 20 is FTP, 25 is SMTP) but they can also be assigned as needed. To access a specific port you append a colon to the URL followed by the port number. If a port number is not supplied then it will default to port 80 (HTTP). When we write google.co.uk we really mean 216.58.198.227:80

That's all I want to cover for this post. There's more we could talk about such as subnets, classes, MAC addresses and ARP but I'd prefer to keep this post brief so maybe I will do a part 2 at a later date. I hope you've found this post useful, feel free to get in touch with any comments / questions, see you next time. 😃

Top comments (0)