Binary Search is an algorithm that finds the position of a target value in a sorted list. The algorithm exploits the fact that the list is sorted, and is devised such that is does not have to even look at all the n elements, to decide if a value is present or not. In the worst case, the algorithm checks the log(n) number of elements to make the decision.

Binary Search could be tweaked to output the position of the target value, or return the position of the smallest number greater than the target value i.e. position where the target value should have been present in the list.

Things become more interesting when we have to perform an iterative binary search on k lists in which we find the target value in each of the k lists independently. The problem statement could be formally defined as

Given

klists ofnsorted integers each, and a target valuex, return the position of the smallest value greater than or equal toxin each of theklists. Preprocessing of the list is allowed before answering the queries.

The naive approach - k binary searches

The expected output of this iterative search is the position of the smallest value greater than or equal to x in each of the k lists. This is a classical Binary Search problem and hence in this approach, we fire k binary searches on k lists for the target value x and collect the positions.

Python has an in-built module called bisect which has the function bisect_left which outputs the smallest value greater than or equal to x in a list which is exactly what we need to output and hence python-based solution using this k-binary searches approach could be

import bisect

arr = [

[21, 54, 64, 79, 93],

[27, 35, 46, 47, 72],

[11, 44, 62, 66, 94],

[10, 35, 46, 79, 83],

]

def get_positions_k_bin_search(x):

return [bisect.bisect_left(l, x) for l in arr]

>>> get_positions_k_bin_search(60)

[2, 4, 2, 3]

Time and Space Complexity

Each of the k lists have size n and we know the time complexity of performing a binary search in one list of n elements is O(log(n)). Hence we deduce that the time complexity of this k-binary searches approach is O(klog(n)).

This approach does not really require any additional space and hence the space complexity is O(1).

The k-binary searches approach is thus super-efficient on space but not so much on time. Hence by trading some space, we could reap some benefits on time, and on this exact principle, the unified binary search approach is based.

Unified binary search

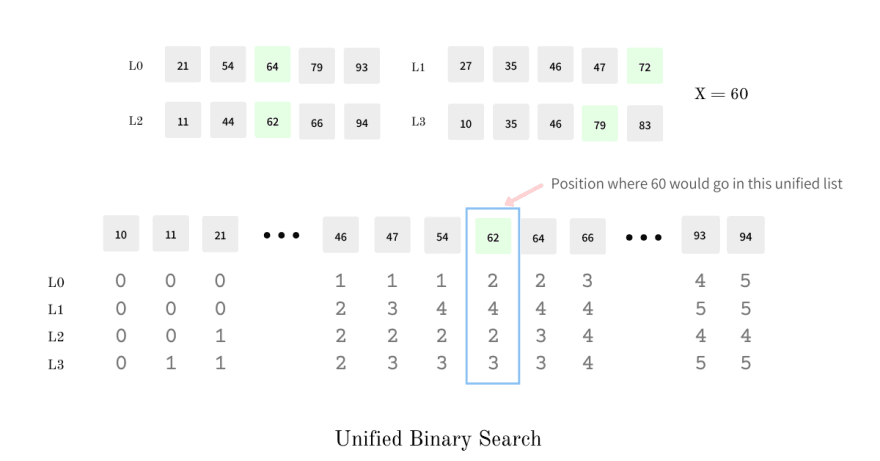

This approach uses some extra space, preprocessing and computations to reduce search time. The preprocessing actually involves precomputing the positions of all elements in all the k lists. This precomputation enables us to perform just one binary search and get the required precalculated positions in one go.

Preprocess

The preprocessing is done in two phases; in the first phase, we compute a position tuple for each element and associate it with the same. In phase two of preprocessing, we create an auxiliary list containing all the elements of all the lists, on which we then perform a binary search for the given target value.

Computing position tuple for each element

Position tuple is a k item tuple where every ith item denotes the position of the associated element in the ith list. We compute this tuple by performing a binary search on all the k lists treating the element as the target value.

From the example above, the position tuple of 4th element in the 4th list i.e 79 will be [3, 5, 4, 3] which denotes its position in all 4 lists. In list 1, 79 is at index 3, in list 2, 79 is actually out of bounds but would be inserted at index 5 hence the output 5, we could also have returned a value marking out of bounds, like -2, in list 3, 79 is not present but the smallest number greater than 79 is 94 and which is at index 4 and in list 4, 79 is present at index 3. This makes the position tuple for 79 to be [3, 5, 4, 3].

Given a 2-dimensional array arr we compute the position tuple for an element (i, j) by performing a binary search on all k lists as shown in python code below

for i, l in enumerate(arr):

for j, e in enumerate(l):

for k, m in enumerate(arr):

positions[i][j][k] = int(bisect.bisect_left(m, e))

Creating a huge list

Once we have all the position tuples and they are well associated with the corresponding elements, we create an auxiliary list of size k * n that holds all the elements from all the k lists. This auxiliary list is again kept sorted so that we could perform a binary search on it.

Working

Given a target value, we perform a binary search in the above auxiliary list and get the smallest element greater than or equal to this target value. Once we get the element, we now get the associated position tuple. This position tuple is precisely the position of the target element in all the k lists. Thus by performing one binary search in this huge list, we are able to get the required positions.

Complexity

We are performing binary search just once on the list of size k * n hence, the time complexity of this approach is O(log(kn)) which is a huge improvement over the k-binary searches approach where it was O(klog(n)).

This approach, unlike k-binary searches, requires an additional space of O(k.kn) since each element holds k item position tuple and there are in all k * n elements.

Fractional cascading is something that gives us the best of both worlds by creating bridges between the lists and narrowing the scope of binary searches on subsequent iterations. Let's find out how.

Fractional Cascading

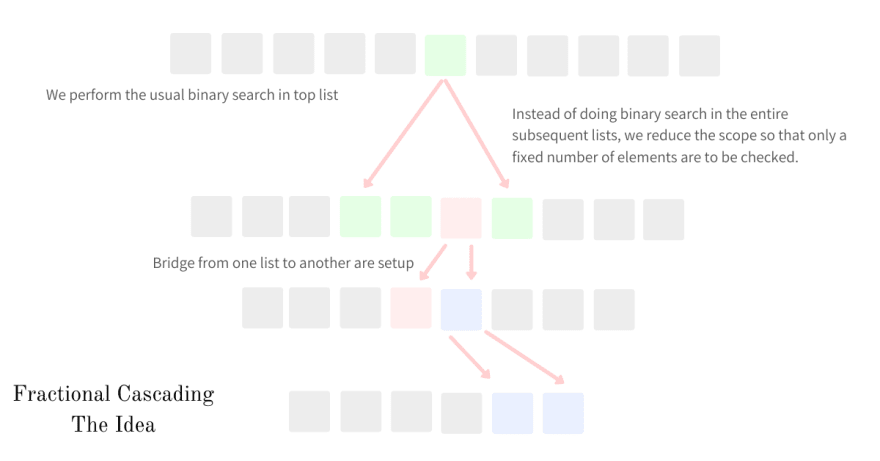

Fractional cascading is a technique through which we speed up the iterative binary searches by creating bridges between the lists. The main idea behind this approach is to dampen the need to perform binary searches on subsequent lists after performing the search on one.

In the k-binary searches approach, we solved the problem by performing k binary searches on k lists. If, after the binary search on the first list, we would have known a range within which the target value was present in the 2nd list, we would have limited our search within that subset which helps us save a bunch of computation time. The bridges, defined above, provides us with a shortcut to reach the subset of the other list where that target value would be present.

Fractional cascading is just an idea through which we could speed up binary searches, implementations vary with respect to the underlying data. The bridges could be implemented using pointers, graphs, or array indexes.

Preprocess

Preprocessing is a super-critical step in fractional cascading because it is responsible for speeding up the iterative binary searches. Preprocessing actually sets up all the bridges from all the elements from one list to the range of items in the lower list where the element could be found. These bridges then cascade to all the lists on the lower levels.

Create Auxiliary Lists

The first step in pre-processing is to create k auxiliary lists from k original lists. These lists are created bottom-up which means lists on the lower levels are created first - M(i+1) is created before M(i). An auxiliary list M(i) is created as a sorted list of elements of the original list L(i) and half of the previously created auxiliary list M(i+1). The half elements of auxiliary lists are chosen by picking every other element from it.

By picking every other element from lower-level lists, we fill the gaps in value ranges in the original list L(i), giving us a uniform spread of values across all auxiliary lists. Another advantage of picking every other element is that we eradicate the need for performing binary searches on subsequent lists altogether. Now we only need to perform a binary search for list M(0) and for every other list, we only need to check the element we reach via the bridge and an element before that - a constant time comparison.

Position tuples

A position tuple for Fractional Cascading is a 2 item tuple, associated with each element of the auxiliary list, where the first item is the position of the element in the original list on the same level - serving as the required position - and the second element is the position of the element in the auxiliary list on the lower level - serving as the bridge from one level to another.

The position tuple for each element in the auxiliary array can be created by doing a binary search on the original list and the auxiliary list on the lower level. Given a 2-dimensional array arr and auxiliary lists m_arr we compute the position tuples for element (i, j) by performing a binary search on all k original and auxiliary lists as shown in python code below

for i, l in enumerate(m_arr):

for j, m in enumerate(m_arr[i]):

pointers[i][j] = [

bisect.bisect_left(arr[i], m_arr[i][j]),

bisect.bisect_left(m_arr[i+1], m_arr[i][j]),

]

Fractional Cascading in action

We start by performing a binary search on the first auxiliary list M(0) from which we get the element corresponding to the target value. The position tuple for this element contains the position corresponding to the original list L(0) and bridge that will take us to the list M(1). Now when we move to the list M(1) through the bridge and have reached the index b.

Since auxiliary lists have uniform range spread, because of every other element being promoted, we are sure that the target value should be checked again at the index b and b - 1; because if the value was any lower it would have been promoted and bridged to other value and hence the trail we trace would be different from what we are tracing now.

Once we know which of the b and b-1 index to pick (depending on the values at the index and the target value) we add the first item of the position tuple to the solution set and move the auxiliary list on the lower level and the entire process continues.

Once we reach the last auxiliary list and process the position tuple there and pick the element, our solution set contains the required positions and we can stop the iteration.

def get_locations_fractional_cascading(x):

locations = []

# the first and only binary search on the auxiliary list M[0]

index = bisect.bisect_left(m_arr[0], x)

# loc always holds the required location from the original list on same level

# next_loc holds the bridge index on the lower level

loc, next_loc = pointers[0][index]

# adding loc to the solution

locations.append(loc)

for i in range(1, len(m_arr)):

# we check for the element we reach through the bridge

# and the one before it and make the decision to go with one

# depending on the target value.

if x <= m_arr[i][next_loc-1]:

loc, next_loc = pointers[i][next_loc-1]

else:

loc, next_loc = pointers[i][next_loc]

# adding loc to the solution

locations.append(loc)

# returning the required locations

return locations

The entire working code could be found here github.com/arpitbbhayani/fractional-cascading

Time and space complexity

In Fractional Cascading, we perform binary search once on the auxiliary list M(0) and then make k constant comparisons for each of the subsequent levels; hence the time complexity is O(k + log(n)).

The auxiliary lists could at most contain all the elements from the original list plus 1/2 |L(n)| + 1/4 |L(n-1)| + 1/8 |L(n-2)| + ... which is less than all elements of the original list combined. Thus the total size of the auxiliary list cannot exceed twice the original lists. The position tuple for each of the elements is also a constant 2 item tuple thus the space complexity of Fractional Cascading is O(kn).

Thus Fractional Cascading has time complexity very close to the k-binary searches approach with a very low space complexity as compared to the unified binary searches approach; thus giving us the best of both worlds.

Fractional Cascading in real world

Fractional Cascading is used in FD-Trees which are used in databases to address the asymmetry of read-write speeds in tree indexing on the flash disk. Fractional cascading is typically used in range search data structures like Segment Trees to speed up lookups and filters.

References

- Fractional Cascading - Wikipedia

- Fractional Cascading - Original Paper by Bernard Chazelle and Leonidas Guibas

- Fractional Cascading Revisited

- Fractional Cascading - Brown University

Other articles you might like:

- Copy-on-Write Semantics

- What makes MySQL LRU cache scan resistant

- Building Finite State Machines with Python Coroutines

- Solving an age-old problem using Bayesian Average

- Pseudorandom numbers using Cellular Automata - Rule 30

This article was originally published on my blog - Fractional Cascading - Speeding up Binary Searches.

If you liked what you read, subscribe to my newsletter and get the post delivered directly to your inbox and give me a shout-out @arpit_bhayani.

Top comments (0)