This is the second installment in my Testing series. It will not be a big wall of text with a lot of theory - this one comes with exemples from my personal experience.

Intro

If you use an open-source library, or work on an open-source project, sometimes it will not be documented at all, and the author will tell you to just read the source code.

Sometimes, the documentation is good - just out of date. Other times, it will be incomplete, and in some cases, it may be awesome, and tell you everything you need to know (but still not cover the way the library works internally).

Reading the tests will often teach you more quicker than reading the source code.

Writing software requires both theory and practice. In order to become good at it, you should write a lot of code, and you need to make mistakes that you can learn from. That is the practice bit.

You also need to read a lot of code, in books, but ideally, also in open-source projects. That will give you theory, and show you how other people solve problems.

The problem with this is that oftentimes, projects are mature, and have a massive codebase, which means you may not know where to start. My recommendation: always start by running the test suite, then read the tests. It will often teach you more quicker than reading the source code, or sometimes even the documentation.

Also, reading tests will help you see how others write tests, what they test, and may help you think about your own testing strategies.

Examples

Example 1: polyquack

polyquack is a Python library for translations that I have written so I could use it in polyquack-django - an extension to help write translatable websites with Django. polyquack-django solves some pain points that I didn't like with other translation packages, mostly in that it extends PostgreSQL JSONFields to make translations dynamic, unlike some packages that need to create new tables, or columns for each language.

polyquack has a pluralization function, and the pluralization rules are briefly covered in the documentation, but it doesn't really explain everything that happens behind the scenes (note that it's an alpha stage project, so I am sure the documentation will be improved in the future).

So, how does it work? If you use the Pluralizable class, there is a function that takes a language code and a count, and returns the proper string.

# This is an example using a special Pluralizable class defined in the package.

song_forms = {

"en": ["song", "songs"],

"pl": ["piosenka", "piosenki", "piosenek"],

}

song = pluralization.Pluralizable(forms=song_forms)

# prints "I am listening to a song"

print(f"I am listening to a {song.pluralize_by_language('en', 1)}")

""" prints:

0 piosenek

1 piosenka

2 piosenki

3 piosenki

5 piosenek

10 piosenek

"""

for i in [0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10]:

print(f"{i} {song.pluralize_by_language('pl', i)}")

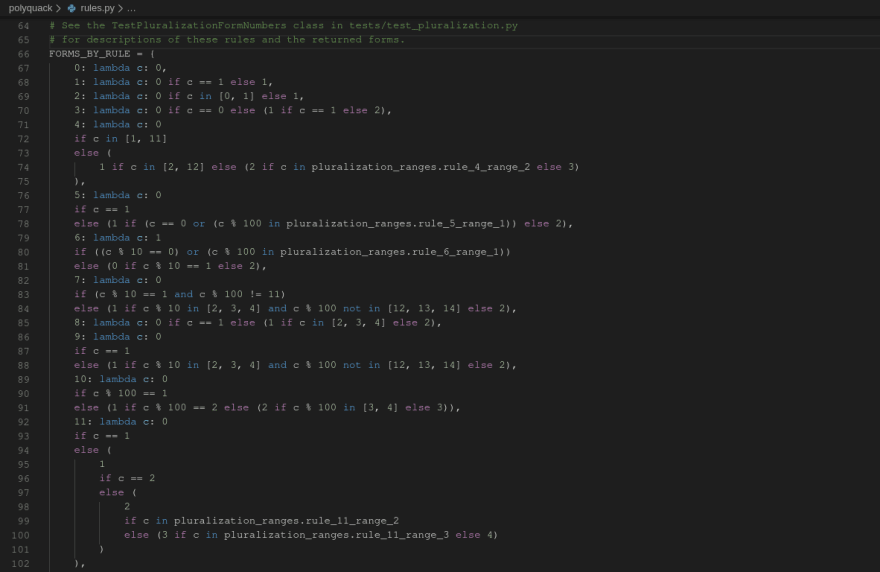

Internally, there is an indexed dict that returns a function based on the rule number (and languages are tied to rule numbers). The function takes one argument (a count), and returns the correct plural form. All well and good, now how does the code look?

A lot of lambda functions with an argument c (our count), and many conditionals. Some might argue that it's hard to read, but I personally find it quite elegant. Admittedly, it needs to be properly documented, and the comment at the top tells us to look at the tests.

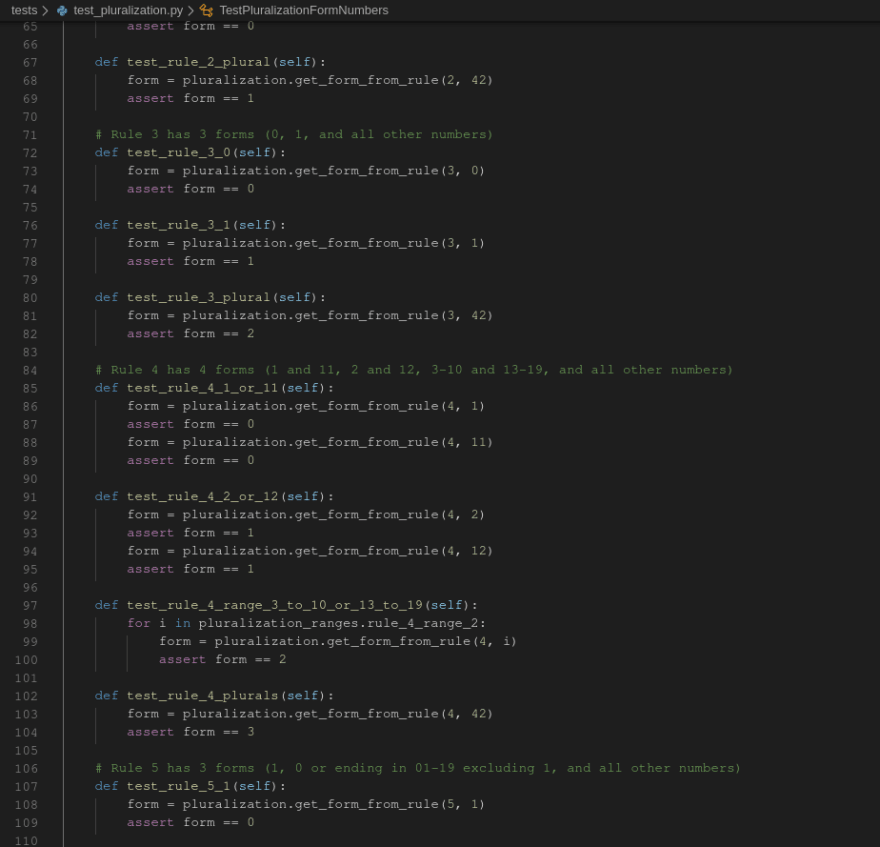

Right away, we can see that we simply call the pluralization.get_form_from_rule() function with two arguments (the rule number, and a count), and it returns the form number (0 to n-1, with different languages having a different number n of forms). The test function names tell us what rule we are testing, and the counts, and describe the rules - same as the documentation.

It makes the actual dict really easy to comprehend, IMHO.

(The complete test suite can be found here if you're interested - I learned a lot about grammar rules in various languages while writing this library and found it fascinating.)

Example 2

This is more of an anecdote than code example. Some time ago, I was tasked with writing a Java app to decrypt a Google Pay payload using Google's Tink library.

I couldn't find any practical examples of what I needed to do, or even the functions I needed to use in the documentation. I simply opened the tink/java/src/test/ folder, finally found a working example, used that as a basis for my own code, and it worked.

Conclusion

Hopefully, you have seen another benefit of writing tests with your code. It helps document the code (for developers, not necessarily for end-users), and can make it easy to understand how the code works internally, or how to use it in practice.

Have you ever refered to tests to understand a piece of code before it finally clicked?

Will you start writing tests to document your code, not just to ensure it works?

Oldest comments (0)