My head is 🤯 after investing the previous week in Kent C Dodd's Testing Javascript course (Very much worth the effort if you ever feel in doubt about testing confidence)

Today I took a step back and started looking at how I approach my projects, and my git commits in previous projects are an abstraction of that approach, where I would tackle big picture things in a single commit.

After having the boat-load of information absorbed, I needed a tangent to recuperate, and so I started thinking about the redo on my website that I'm going to tackle. I ended up getting distracted for a day on a Gatsby starter with some testing utilities like Typescript, Jest, and Cypress - that's for another day. For let's say the combination of the three led to some different configs (Looking at you Gatsby + Jest!) and type declarations (Jest & Cypress).

So today I got looking at how to integrate a TDD paradigm into my workflow, and as I've said, I typically look at my Git Commits for that. I used to be a sucker for directly injecting to my master branch 😅. However, I now know better.

So after a bit of digging into best practices and working with writing tests first, then code that will pass those tests; I present my rubber ducked flow. I call it that, because this is me, trying to explain git, TDD, and whatever else to the community while trying to solve my problem and coming up with the solution doing so.

So let's step through it;

GIT

Git is, in effect, a command-line based way to retain a different version of files. It can be run locally and sent to a remote repository like Github, Gitlab, or Bitbucket. This way, other people can utilise it to work together.

It isn't straightforward when you realise that there are many versions either in an archive or actively being worked. But don't worry about that just yet. Just focus on the small picture. Just know, that a reference to PR or Pull-Request is 'asking permission' to merge to different existences together.

Funny thing, I first used

gitto play KSP with my friends by sharing a repo of the save files and contributing different launch missions and ships. Super nerdy way to bring multiplayer to a game

TDD

'Test Driven Development' operates on the idea of writing tests for what you intend before you create it. Something like working in a traffic-light system you would say

🔴 Write tests of your intention.

🟢 Write code that makes those tests pass.

🟡 Refactor that code for optimisation or performance.

On top of that analogy, there are further four types of testing.

Static - Make sure there aren't any typos or type-errors (in Typescript). A common term for this is linting, like, ESLint etc. Most static tests are baked into, or plugged into amazing text editors or IDE's these days.

Unit - Does the code do what you think it does? Given two numbers, 1 and 1, the function returns 2 without doing anything else. Does it handle errors like passing a string rather than a number? Is the dom node filled out correctly with all a11y requirements for pure accessibility?

console: Give me a number, dummy!

Maybe it's a super functional and will accept an array of numbers too. 🎉

Integration - This is where your code plays nice with other code it's needing or interacts. With given data from an API, does the react/vue/svelt/HTML element do what you expect. As well as making sure the children elements are doing what they're supposed to.

End-to-End - From the developer's end to the user's end, is it all working cohesively? Can the user go through the motions of the site/app/program, and do that job-to-be-done without issue or error?

My Opinionated Workflow

Let me bring you back to my new flow in my projects going forward:

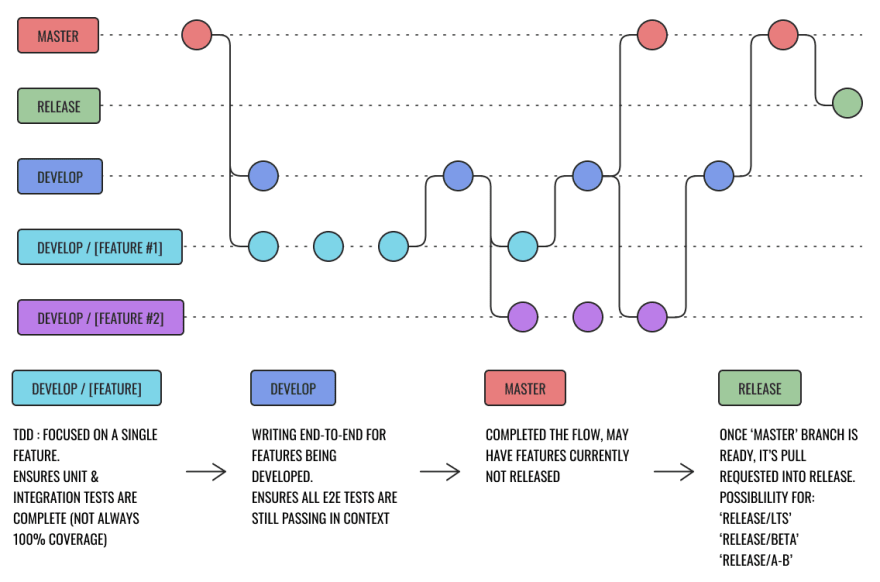

Git repos work like trees, a master trunk branches off different iterations of the same project. So from there, I've branched off release, develop, and develop/*. master only exists because of being automatically created at the beginning. So you see I immediately branch into develop and develop/*.

In the beginning, develop/* is where I'll live, writing unit and integration tests that will fail before nothing else. This branch is where I'll be blueprinting my intentions for the feature—ensuring that I've completed error handling too where necessary.

On this hypothetical chart, develop/[feature #1] (The Cyan coloured, 4th row) has a couple of commits. Here might be where I'm sharing my code with others asking for help (Another great use of shared remote repos!) and once I'm comfortable with my tests, code, and refactor, committing a PR to the develop branch.

Always make a new branch when wanting to make a change to something existing, and always PR to merge it back in

develop is a moment to check End-to-End tests. Maybe it introduced a new bug no present previously. My latest feature might create an a11y issue previously unseen.

Once everything is kosher, I can make another PR to the master branch to keep it as the one branch that is 'pure', where everything is working as intended and for my best knowledge, all tests are passing which means 🤞 - no bugs for the 90+% of users.

This mentality to my commits will also mean that my master branch might have code in it that's subject to change later, or yet utilised. Maybe this feature is purely integrating a service API or an algorithm, but its implementation is in a completely different realm.

In the chart, I also have a develop/[feature #2] branch, but the interesting one you'll see is that once it's gone through the motions, I have another branch. release. I'll keep this purely as an anchor point to where the master branch has everything that's needed to publish to the public. This way, I can keep on working on the next tests, the upcoming features, without worrying.

If I'm working on a project with Continous Deployment like Netlify, if I committed to my master branch, I could potentially send a request to Netlify to rebuild my website and publish these new developments that aren't ready for the public to utilise.

And there we have it; my rubber duck debugged git workflow!

I've started to enjoy these write-ups, I'm aiming for a more opinionated perspective than any tutorial. There are so many tutorials out there already that it wouldn't be beneficial for anyone. Instead, I'm aiming to document those moments of overlooked thought process when arriving at the result. Likewise, let me know your thoughts!

✌️

Top comments (0)