Eventual Consistency in Kubernetes and the Real World™

It was once acceptable — and even expected — for web services to go down for maintenance or when under heavy load. You could run a simple LAMP stack on a single physical machine and call it a day. Today, however, services are measured in the number of nines of availability they provide. A single server no longer cuts it.

One way to achieve higher availability is by running countless copies, or replicas, of our services across geographies. Now, though, we've got ourselves a distributed system to wrangle! This is cool, it can add a shiny new buzzword to your resume, but it also brings along its own challenges.

You've now got to...

- Keep n servers up to date with the latest operating system patches

- Ensure that they are all running the correct version of your service

- Prevent configuration drift across them all

- Orchestrate rollouts of new code and configuration

- Handle network partitions between servers

- Etc. ...

Platforms such as Kubernetes and Cloud Foundry can solve many of these problems. There are a few they can't avoid, however.

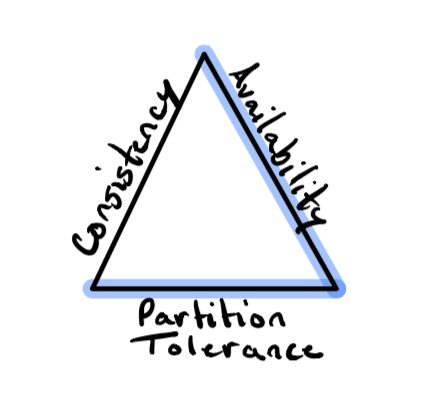

CAP Theorem and Kubernetes

The CAP Theorem posits that a stateful distributed system can guarantee at most two of the following properties:

- Consistency - every read request is guaranteed to either receive the most current data or fail

- Availability - ability to continue serving requests without the guarantee that the response contains the most current data

- Partition Tolerance - resiliency in the event of dropped or degraded network communication between nodes

There is no right answer when it comes to selecting which two CAP properties your distributed system will guarantee. It's all about tradeoffs. If you're designing a distributed database to store financial transactions for a bank, you'll want to favor Consistency over Availability in the event of a network partition. The cost of returning incorrect financial information is simply too high.

However, if you're designing a distributed system to manage a highly available web service deployment, you'll surely want to choose Availability over Consistency. If some portion of your services is running out of date code or configuration, so be it. At least they're still serving customer requests instead of errors!

Since Kubernetes is optimized for running resilient, highly available workloads, it chooses Availability. State updates are propagated over time in what is known as eventual consistency. Eventual consistency means that if no new updates are made to a system, then eventually, the system will converge. This means that eventually, all nodes will reflect the most current update and be Consistent. There are no guarantees around how long this "eventually" will take. In the event of a crashed process, it could be less than a second. If a network cable is unwittingly unplugged, it could take days. All that is "guaranteed" is that an eventually consistent system will try to make the desired state of the system into its actual state.

What is Desired and Actual State?

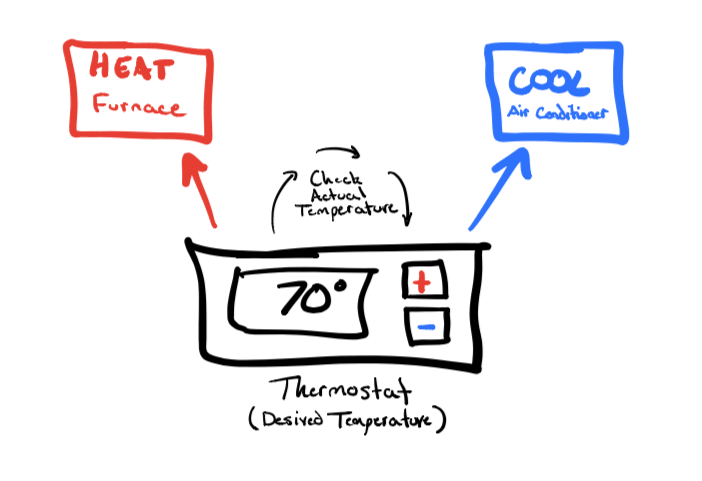

To make this all a bit more concrete, let's consider a real-world distributed system that we're all aware of: a household HVAC system.

When you set the temperature on the thermostat to 70 degrees, what you're really doing is requesting that the temperature be 70 degrees. Setting the temperature on the thermostat does nothing on its own. However, the thermostat will work together with the furnace and air conditioner to make this request a reality. In other words, the HVAC system will work to make this desired state (thermostat) into the actual state of your home.

If the actual temperature is 65 degrees, the thermostat will turn on the furnace and periodically check to see if the room has reached the desired temperature. Likewise, if the actual temperature is 75 degrees, it will turn on the air conditioner. The thermostat will do this monitoring in perpetuity in what is known as a control loop.

Now let's consider a "network partition" scenario. The temperature in the room is 75 degrees, and someone has unplugged the air conditioner to save energy. In this case, convergence to 70 degrees could potentially take a very long time. Eventually, though, someone will plug the air conditioner back in (or it will get cold enough outside), and the room will reach its desired temperature. That's eventual consistency for you!

So, to summarize:

- Desired State is the state that you want the system to be in

- Actual State is the state that the system is actually in

A Note on Perceived State

You may have seen references to something called "Perceived State." I like to think of this as merely being a qualifier on the concept of "Actual State." Philosophically it's referring to our inability to distinguish what we can perceive through our senses from "true" reality. Think Plato's Allegory of the Cave.

Practically, in distributed systems "Perceived State" refers to the imprecision of our measurements and lag time between when the system was measured and when we observe the results. In the HVAC example, you can think of the current temperature reported by the thermostat as being the Perceived State and know that the Actual State may have changed slightly since the temperature was last probed.

Desired State in Kubernetes

All Kubernetes objects have spec and status subobjects. You can think of spec as being the specification of the object. This is the section where you declare the Desired State of the resource, and Kubernetes will try its hardest to make it so. The status section, on the other hand, is not meant to be touched. This is where Kubernetes provides visibility into the Actual State of the resource. If you wish to learn more, I recommend reading the following architecture docs about Kubernetes API conventions.

Desired State Example

Now let's dive a bit deeper with some concrete examples of eventual consistency in Kubernetes. I'll be using a small test cluster running on Digital Ocean that has two worker nodes. Each node is running other workloads (such as Contour for ingress), but we should have enough headroom to run three 256M Pods on each. This is a managed cluster, so Digital Ocean is taking care of the master nodes for us.

Think back to our web service scenario where we mentioned that we wanted to be able to do the following:

Have multiple replicas of our application for high availability

Keep code and configuration in sync across these replicas

Be resilient in the event of application and infrastructure failures

Kubernetes makes this task simple with its Deployment resource. Deployments allow us to provide a template for the workloads we want to run as well as the number of replicas and the strategy for rolling out updates.

# example-deployment.yaml

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: example-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: httpbin

replicas: 5

strategy:

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: 25%

maxUnavailable: 25%

type: RollingUpdate

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: httpbin

spec:

containers:

- name: httpbin

image: kennethreitz/httpbin:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 80

env:

- name: VERSION

value: "1.0.0"

resources:

requests:

memory: "256M"

In the Deployment above, we declare that we want to five two replicas of our web service (httpbin) and that each needs 256M of memory to run. We also specify that we want it to perform rolling updates with at most one-quarter of the Pods being updated at a given time. Let's apply it:

$ kubectl apply -f example-deployment.yaml

Wait a few seconds and then view the deployments and pods that are running:

$ kubectl get deployments

NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE

example-deployment 5/5 5 3 12s

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

example-deployment-58958c58d9-229qp 1/1 Running 0 25s

example-deployment-58958c58d9-cwbzp 1/1 Running 0 25s

example-deployment-58958c58d9-hgf52 1/1 Running 0 25s

example-deployment-58958c58d9-mr5kp 1/1 Running 0 25s

example-deployment-58958c58d9-nkwbn 1/1 Running 0 25s

Our cluster is now running five replicas of our web service across its two worker nodes.

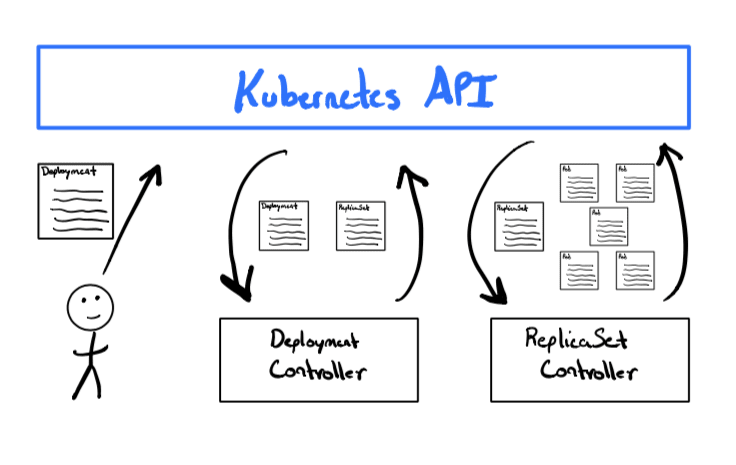

So what just happened here? Think back to our thermostat example. The thermostat took the occupant's desired temperature as input and then acted on the actual temperature by either turning up the furnace or air conditioner. Kubernetes does something similar by continuously watching the state of API resources using components known as controllers.

On Kubernetes we created a Deployment that defined how we want our applications to run on the cluster. The built-in Deployment controller observed this and then created a ReplicaSet to represent our group of Pod replicas. The ReplicaSet controller saw this happened and spun up five Pods based on the template we specified in our Deployment. If all of that sounded like a bunch of Kubernonsense, perhaps the diagram below will help you visualize it.

Now let's take a closer look at our Deployment:

$ kubectl get deployment example-deployment -o yaml

The first thing you'll notice is that there's a whole lot more YAML than what we initially declared. Not only has the spec section been filled in with some additional defaults, but we now have a status section revealing the Actual State of our Deployment.

status:

availableReplicas: 5

conditions:

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:47Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:47Z"

message: Deployment has minimum availability.

reason: MinimumReplicasAvailable

status: "True"

type: Available

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:23Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:48Z"

message: ReplicaSet "example-deployment-58958c58d9" has successfully progressed.

reason: NewReplicaSetAvailable

status: "True"

type: Progressing

observedGeneration: 1

readyReplicas: 5

replicas: 5

updatedReplicas: 5

Here we see that of the five replicas we requested, we have five that are ready (running).

Losing a Pod

Let's delete a pod to simulate one of our applications crashing:

$ kubectl delete pod example-deployment-58958c58d9-nkwbn --wait=false

Now quickly look at the Deployment again:

$ kubectl get deployment example-deployment -o yaml

status:

availableReplicas: 4

conditions:

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:47Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:47Z"

message: Deployment has minimum availability.

reason: MinimumReplicasAvailable

status: "True"

type: Available

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:23Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:48Z"

message: ReplicaSet "example-deployment-58958c58d9" has successfully progressed.

reason: NewReplicaSetAvailable

status: "True"

type: Progressing

observedGeneration: 1

readyReplicas: 4

replicas: 5

unavailableReplicas: 1

updatedReplicas: 5

The status has been updated to reflect that only four of the five pods are running. The ReplicaSet controller will quickly remedy this by creating a new Pod, so you have to act quickly to see the Deployment in this state. Also, it's important to note that the Deployment's spec did not change at all since our Desired State remains the same.

Losing a Node

Now let's consider the case of a network partition. Imagine that someone tripped over an ethernet cable and left an entire server rack unreachable. We can simulate this by deleting a node from our cluster.

Let's look at what happened to our deployment and pods:

$ kubectl get deployments

NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE

example-deployment 3/5 5 3 3h27m

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

example-deployment-58958c58d9-4f2nq 0/1 Pending 0 9m25s

example-deployment-58958c58d9-cwbzp 1/1 Running 0 3h27m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-hgf52 1/1 Running 0 3h27m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-mr5kp 1/1 Running 0 3h27m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-xm7dr 0/1 Pending 0 9m25s

Since we lost a node, we've lost some available capacity. Even though we desired five pods, we can only have enough headroom to run three of them. The Actual State of our Deployment is now:

status:

availableReplicas: 3

conditions:

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:23Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T19:20:48Z"

message: ReplicaSet "example-deployment-58958c58d9" has successfully progressed.

reason: NewReplicaSetAvailable

status: "True"

type: Progressing

- lastTransitionTime: "2020-02-02T22:38:47Z"

lastUpdateTime: "2020-02-02T22:38:47Z"

message: Deployment does not have minimum availability.

reason: MinimumReplicasUnavailable

status: "False"

type: Available

observedGeneration: 1

readyReplicas: 3

replicas: 5

unavailableReplicas: 2

updatedReplicas: 5

Going back to our thermostat example, you can think of this situation as analogous to the air conditioner being unplugged and unresponsive. However, if we add the node back to the worker pool, the control loops will eventually reconcile this.

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

example-deployment-58958c58d9-4f2nq 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 30m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-cwbzp 1/1 Running 0 3h48m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-hgf52 1/1 Running 0 3h48m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-mr5kp 1/1 Running 0 3h48m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-xm7dr 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 30m

That's eventual consistency in action!

Deploying New Code and Configuration

So far, we've looked at a couple failure scenarios that caused the actual number of running pods to be lower than what we desired. Let's now consider a rollout of updated configuration to our Deployment.

Let's add an additional environment variable creatively named NEW_ENVIRONMENT_VARIABLE:

$ kubectl edit deployment example-deployment

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

...

name: example-deployment

...

spec:

...

replicas: 5

...

template:

metadata:

...

spec:

containers:

- env:

- name: VERSION

value: 1.0.0

- name: NEW_ENVIRONMENT_VARIABLE

value: hello there!

image: kennethreitz/httpbin:latest

...

status:

...

This will cause the Deployment to gradually rollout a new set of Pods that meet this new Desired State. It does this by scaling down the existing ReplicaSet and creating a new one that matches the updated Pod template.

You can view this by observing the ReplicaSets and Pods that are running on the cluster:

$ kubectl get replicasets

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE

example-deployment-58958c58d9 0 0 0 3h52m

example-deployment-9787854b4 5 5 5 39s

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

example-deployment-58958c58d9-4f2nq 1/1 Running 0 33m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-cwbzp 1/1 Running 0 3h51m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-hgf52 1/1 Running 0 3h51m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-mr5kp 1/1 Running 0 3h51m

example-deployment-58958c58d9-xm7dr 0/1 Terminating 0 33m

example-deployment-9787854b4-5jm9c 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 3s

example-deployment-9787854b4-wvtb4 0/1 Pending 0 3s

example-deployment-9787854b4-zgvd5 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 3s

During this period, users of the application may temporarily be directed to older Pods, but eventually, all of the original Pods will be replaced. Unfortunately, there's no direct analog thermostat example here. It does, however, tie in nicely with our earlier discussion of the CAP theorem. This showcases how the platform chooses Availability over Consistency.

If the platform waited for the original Pods to be entirely deleted before starting the new ones, clients would surely receive errors. Instead, the Deployment optimizes for no downtime, but with the potential for inconsistent responses. Eventually, though, the platform converges, and we end up with only the five new Pods.

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

example-deployment-9787854b4-5jm9c 1/1 Running 0 9m6s

example-deployment-9787854b4-hkcr9 1/1 Running 0 9m

example-deployment-9787854b4-wvtb4 1/1 Running 0 9m6s

example-deployment-9787854b4-zcnsl 1/1 Running 0 9m1s

example-deployment-9787854b4-zgvd5 1/1 Running 0 9m6s

Summary

We've now explored a few real-world examples of convergence and eventual consistency. Hopefully, they helped clarify what people mean when they refer to Desired and Actual state in Kubernetes. However, if you only take away one thing from this post, just remember the following:

Desired State is what you asked for, but may not reflect reality

Actual State is the state the system is currently in (to the best of our knowledge)

Desired State and Actual State may not always align, but Kubernetes will try its hardest!

Have a happy Palindrome Day (2020-02-02)!* 🤓

* Note: this post on desired vs actual state was originally posted on my blog on 2020-02-02. Unfortunately it must have been 2020-02-03 in UTC by the time I cross-posted to DEV. 😞

Top comments (0)