The strategy design pattern is one of the most widely used patterns in the software development world. In this article, we’re going to learn about the strategy design pattern, when to use it, when not, how we can leverage the pattern to make our design flexible? And we are going to see an example of how to implement it with and without lambdas.

2. Strategy Design Pattern

2.1 Definition

To save you the time spent on searching Wikipedia here is the definition:

The strategy pattern (also known as the policy pattern) is a behavioral software design pattern that enables selecting an algorithm at runtime. Instead of implementing a single algorithm directly, code receives run-time instructions as to which in a family of algorithms to use. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

The idea of the strategy pattern is to define a family of algorithms, encapsulate what varies into separate classes and make their objects interchangeable in the context. Varies here means: may change over time due to the evolving requirements.

2.2 UML Diagram

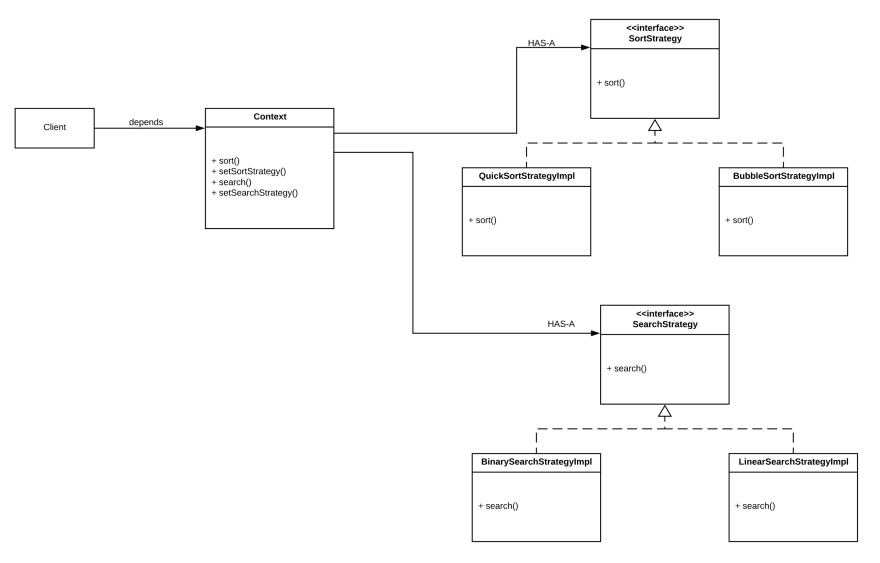

The Context class does not implement any strategy (algorithm). Instead, it maintains a reference to the Strategy interface. The Context class doesn’t care about the implementation of those algorithms. All it knows is that it can perform those algorithms!

StrategyImpl1 and StrategyImpl2 implement the Strategy interface, meaning, implement and encapsulate an algorithm.

2.3 When to use/avoid strategy pattern

Use the strategy pattern when you want to:

Use different algorithms within an object and be able to switch from one algorithm to another at runtime.

Hide irrelevant implementation details of your algorithms from the client. The implementation gets injected to the client at runtime by using a dependency injection mechanism.

Replace massive conditionals with a one-line method call. Note that delegation plays an important role here since that one-line method will call the appropriate implementation at runtime based on the reference type (Dynamic dispatch!).

Substitute inheritance with composition

Avoid using the strategy pattern when your algorithms rarely change, there’s no need to overengineer the program with new classes and interfaces that come along with the pattern

2.4 Classic Strategy in Action

In this example, I’ll show you how to implement the classical strategy pattern in Java. This example simulates a dummy program that sorts and searches a list by using various algorithms (or strategies). To start here is the class diagram of our little demo:

Note that the Client class depends on the Context and also on some of the strategy implementations (I didn’t draw we since we don’t want to have spaghetti here). This is the implementation (dummy) for our demo:

import java.util.List;

interface SortStrategy {

void sort(List<String> list);

}

class QuickSortStrategyImpl implements SortStrategy {

@Override

public void sort(List<String> list) {

System.out.println("List sorted using Quick sort implementation");

}

}

class BubbleSortStrategyImpl implements SortStrategy {

@Override

public void sort(List<String> list) {

System.out.println("List sorted using Bubble sort implementation");

}

}

interface SearchStrategy {

String search(String s);

}

class BinarySearchStrategyImpl implements SearchStrategy {

@Override

public String search(String s) {

System.out.println("list is binary searched");

return null;

}

}

class LinearSearchStrategyImpl implements SearchStrategy {

@Override

public String search(String s) {

System.out.println("list is linearly searched");

return null;

}

}

class Context {

private SortStrategy sortStrategy;

private SearchStrategy searchStrategy;

public Context(SortStrategy sortStrategy, SearchStrategy searchStrategy) {

this.sortStrategy = sortStrategy;

this.searchStrategy = searchStrategy;

}

public void setSortStrategy(SortStrategy sortStrategy) {

this.sortStrategy = sortStrategy;

}

public void setSearchStrategy(SearchStrategy searchStrategy) {

this.searchStrategy = searchStrategy;

}

public void sort(List<String> list) {

sortStrategy.sort(list);

}

public String search(String s) {

// perform search

return searchStrategy.search(s);

}

}

class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> list = List.of("b", "a", "c");

Context context = new Context(new BubbleSortStrategyImpl(), new BinarySearchStrategyImpl());

context.sort(list);

String searchedElement1 = context.search("b");

System.out.println("---------------");

context.setSortStrategy(new QuickSortStrategyImpl());

context.setSearchStrategy(new LinearSearchStrategyImpl());

context.sort(list);

String searchedElement2 = context.search("a");

}

}

Output:

List sorted using Bubble sort implementation

list is binary searched

---------------

List sorted using Quick sort implementation

list is linearly searched

The class Context depends only on the interfaces that declare the strategies, SortStrategy and SearchStrategy. It doesn’t care about the implementation of those interfaces. BubbleSortStrategyImpl and BinarySearchStrategyImpl are classes that implement those interfaces, respectively. As we said previously, they implement and encapsulate the strategy (algorithm).

For example, in line 75 those implementations get injected into the Context class by the client. So when we call the context.sort(list) and context.search(“b”) at runtime, the context will know which implementation to execute (polymorphism).

Notice the class Context exposes setters that let clients replace the strategy implementation associated with the context at runtime (Remember: Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it).

Let’s say we have another requirement to add another sorting or searching strategy implementation, we can add it by implementing the appropriate strategy interface without changing any existing code. You can see that the Strategy design pattern promotes the Open/Closed Principle.

3. Lambda Expression And The Strategy Pattern

3.1 Overview

Lambda expressions have changed the world in Java, and we can effectively use lambda expressions to avoid writing a lot of ceremonial code.

As far as the Strategy design pattern is concerned we don’t have to create a hierarchy of classes. Instead, we can directly pass the strategy implementation of the interface as a lambda expression to the context.

3.2 Strategy simplified

The above code is verbose and has a lot of ceremony for a simple algorithm. We can leverage lambda expression to reduce code verbosity. Using lambda we can implement different versions of an algorithm inside a set of function objects without bloating your code with extra classes.

In this demo, we’ll refactor the code to use lambda expressions to avoid creating custom interfaces and classes. This is the refactored implementation (dummy) code:

class Context {

private Consumer<List<String>> sortStrategy;

private Function<List<String>, String> searchStrategy;

void sort(List<String> list) {

sortStrategy.accept(list);

}

public Context(Consumer<List<String>> sortStrategy, Function<List<String>, String> searchStrategy) {

this.sortStrategy = sortStrategy;

this.searchStrategy = searchStrategy;

}

public void setSortStrategy(Consumer<List<String>> sortStrategy) {

this.sortStrategy = sortStrategy;

}

public void setSearchStrategy(Function<List<String>, String> searchStrategy) {

this.searchStrategy = searchStrategy;

}

public String search(List<String> list) {

return searchStrategy.apply(list);

}

}

class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> list = List.of("b", "a", "c");

Consumer<List<String>> bubbleSort = l -> System.out.println("List sorted using Bubble sort implementation");

Function<List<String>, String> binarySearch = list1 -> {

System.out.println("list is binary searched");

return null;

};

Context context = new Context(bubbleSort, binarySearch);

context.sort(list);

String searchedElement = context.search(list);

System.out.println("-------------");

Consumer<List<String>> quickSort = list1 -> System.out.println("List sorted using Quick sort implementation");

Function<List<String>, String> linearSearch = l -> {

System.out.println("list is linearly searched");

return null;

};

context.setSortStrategy(quickSort);

context.setSearchStrategy(linearSearch);

context.sort(list);

context.search(list);

}

}

Notice I didn’t create any interface because I’m using functional interfaces from java.util.function package.

The output is the same as before. But the important thing to note is I’m not creating classes and interfaces to implement the strategy. All I’m using is composing the Context class with the Consumer and Function interfaces and I’ve created setters so I can change the strategy behavior at runtime.

And, on the client-side, I’m passing the implementations (function object) to the Context class.

4. Conclusion

In this article, we saw the definition of the strategy design pattern, how to use it to make the design flexible. And we learned the classical implementation of the strategy pattern, also its implementation using Java 8 features. In the next article, there will be more Core Java. Stay tuned!

Let us know what you think in the comments below and don’t forget to share!

Top comments (0)