Cover Photo Credit: @gritzko in Chronofold

Any system that has to maintain some kind of state eventually runs into the problem of data consistency. You might have multiple users trying to edit the same document, from a variety of devices, all of which have varying amounts of latency and connection issues. Data consistency is hard. Resiliency means being able to handle these kind of concurrency and availability issues. Approaches to this usually take the form of ACID guarantees, BASE (basically available, eventually consistent) and in the case of CRDT strong eventual consistency. Let's take the example of a realtime collaborative editor.

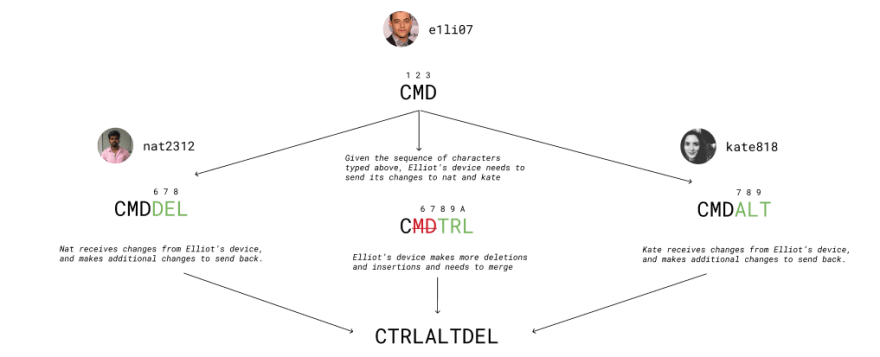

In the above photo, there are 3 different sites where changes are sent and received. Elliot denotes Site 1, Kate is Site 2 and Nat is Site 3. Within Elliot's local document, he types some characters. This change is propagated to Kate and Nat. After which they individually make local changes to their document. Before the changes from Kate and Nat are propagated back, Elliot makes additional changes. The resulting state is the merging of all the changes that have been made.

This is where the result converges deterministically to the same result in every site (despite that there is latency, operations can come out of order, and there is no central server that dictates the source of truth). This is the basis of what Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types can provide.

Strong Eventual Consistency

A few definitions:

-

Site

A network is comprised of sites which include "devices", "peers" operating in parallel, each one producing operations and exchange information with other sites

-

Operations

Events or actions that mutate data

-

Causal Relation

An operation is caused by another operation when it directly modifies or otherwise involves the results of that operation. The ordering by causal relationship determines a linear timeline of operations across the network.

-

Concurrent

If two operations don't have a causal relationship-if they were created simultaneously on different sites without knowledge of each other-they are said to be concurrent

-

Commutativity

A property of the entire system where changing the order of operations does not change the result. This is a fundamental requirement because due to network latency and other issues (offline/connectivity) an editor may not receive the operations or send them until later. We need to be able to guarantee that we get the same result when this happens. Ex:

(3+4 = 4+3). -

Strong Eventual Consistency

Eventually consistent services are often classified as providing (Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual Consistency) in contrast to ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) or rather stating that updates will be observed eventually. Strong eventual consistency has a safety guarantee that any two nodes that have received the same set of updates will deterministically be in the same state. Monotonic systems here also will never rollback.

-

Total Order

State and sequence of operations is guaranteed to be identical on all sites

-

Partial Order

State and sequence of operations is partially guaranteed to be identical on all sites due to logical timestamping or timestamping except in the case of concurrency and the dependency of in what order operations arrive

-

Associative

Rearranging parens in an expression does not change the result / order in which operations are performed does not matter as long as the sequence of the operands is not changed.

-

Idempotent

Operations can be applied multiple times without changing the result beyond the initial application.

-

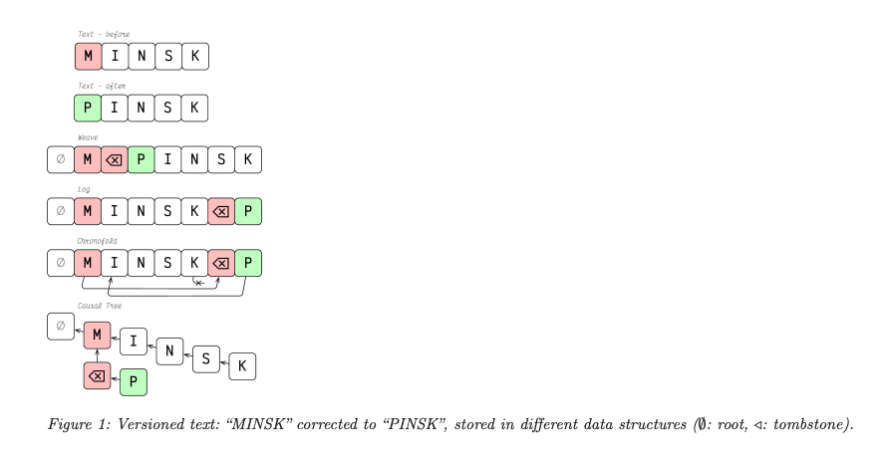

Tombstones

A placeholder value that denotes a delete operation for a corresponding piece of data. Typically tombstones are something that come up when using CRDT with realtime editors. Trade-offs are made around absolute mathematically convergence and limiting offline modes to garbage collect old tombstones that have limited concurrency issues in order to reduce document space complexity.

How do we get events to be in the right order?

Getting events/actions/operations to be in the right order means we need some kind of scheme for timing. We have several ways to do this:

Server Timestamp

We can use the server's timestamp in a typical architecture to serve as the authoritative clock but this isn't available in distributed systems. Furthermore, if we tried to use the different timestamps that are on each of the different nodes we also run into the problem of clock drift.

Clock drifting occurs where a clock does not run at exactly the same rate as a reference clock. It gradually drifts apart or desynchronizes from the other clock. If you've ever had an issue with a remote linux server being drastically off on its timestamps, you need to use ntpdate and ntp to measure this clock drift and synchronization to a reference server.

Logical Timestamps

Time, Clocks, and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System

Leslie Lamport, widely considered to lay the foundation for his work in the theory of distributed systems, published a marvel of work in 1978 on time.

The concept of one event happening before another in a distributed system is examined, and is shown to define a partial ordering of the events. A distributed algorithm is given for synchronizing a system of logical clocks which can be used to totally order the events.

This paper describes what is known as happened before as a way of describing a partial ordering of the events in the system. In that, an event a happens before an event b if a happened at an earlier time than b. Following the fact that real clocks can't be reliable or necessarily used, then happened before has to be defined without using physical clocks.

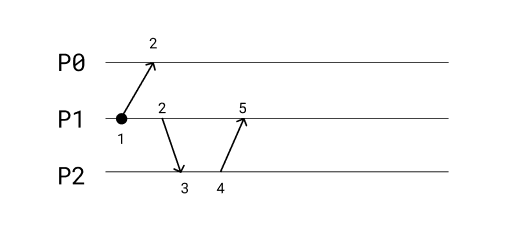

In the above example, we have 3 processes. P0, P1, P2. We know that we have no global clock in this scenario. Instead all we have are messages that being passed around. A logical clock will increment a local timestamp based on whether it is sending or receiving using the following rules:

- Sending: timestamp + 1

- Receiving: Max(local timestamp, sender timestamp) + 1

All processes start at 0 as the root timestamp. In this example, P1 will increment to 1 when it sends to P0. P0 receives this message and its local timestamp is still 0. Since it receives a message it takes the max of these values Max(0, 1) + 1 which would be 2.

P1 sends another message to P2 and does so by incrementing its now local timestamp again from 1 to 2. P2 receives this message and must take the Max(0, 2) + 1 which is 3. P2 sends a message to P1 and must increment its local timestamp from 3 to 4. P1 receives this message and takes the Max(2, 4) + 1 which is 5. Doing this kind of ordering helps us get closer to total ordering.

Event Logs

In enterprise circles, this is typically called event sourcing, where every operation is stored as data and playback is used when you need to construct the model.

The fundamental idea of Event Sourcing is that of ensuring every change to the state of an application is captured in an event object, and that these event objects are themselves stored in the sequence they were applied for the same lifetime as the application state itself.

Given that we have a complete timeline of all the operations that ever occurred in the state, we can replay/query/rebuild all or part of the compute history. To give a log total ordering we need to sort operations by time and then by unique origin.

Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types

Given that the focus of our problem is how to prevent inconsistencies between different sites, we need an approach that makes it mathematically always possible to merge and resolve concurrent updates without conflicts. CRDTs provide us with strong eventual consistency and there are two approaches:

State-based CRDTs (CvRDTs)

State based CRDTs send their full local state to other sites. Merging is done by a function which must be commutative, associative, and it must be idempotent. An update also must monotonically increase the internal state, which is to say that the state always grows, even with deletions.

A good example of CvRDTs is in gossip protocols where the state of a replica is propagated and merged with other replicas when topologies change and help reduce network use when these states change.

Operation-based CRDTs (CmRDTs)

Operation based CRDTs, as the name implies, only require sites to exchange the operations themselves. Operations are commutative, but they are not necessarily idempotent. This means that infrastructure must take into account that all operations on a site are delivered without duplication, but can be in any order. Because a deletion is just a placeholder (called a tombstone), an operation can always commute. This means something like the example in the figure where Site 1 deletes MD still translates fine to changes made on other sites since the characters are never really gone.

Unique Identifiers

In almost every implementation of CRDT with respect to text, every character in the document has a unique identifier. Conflicts due to merging are all resolved by this unique identifier plus a logical timestamp per character (usually a Lamport Timestamp).

Questions on implementations and use cases

Having read through much of the literature, it's clear that there are a series of questions that need to be asked in order to properly define what kind of implementation should be selected. These questions might include:

- How do you represent the data in the form of CRDTs

- What does space and time complexity look like for insert, delete, update operations to those structures

- How is state represented, how are operations (in the sense of events/actions as noted above) represented and stored

- What guarantee tradeoffs are made based on the implementation chosen?

- Do operations like deletions leave behind placeholders for deletions or avoid tombstones in favor of reduced space complexity while trading off for less guarantees around convergence due to interleaving concurrent edits.

- What about garbage collection for old versions and edits where tombstones are no longer referenced? In the case of garbage collection, you might decide that after 1 week you might safely say that those edits will not run into concurrency problems due to additional edit/merges. (Some editors resolve this problem entirely by not allowing offline editing)

But the most important question you should be asking:

What are actual real-word performance and usability characteristics based on the intended usage of the application?

Figma

Consider how Figma makes these tradeoffs by combining multiple CRDT-inspired techniques (associativity, commutativity, idempotent) with a last-write-wins (LWW) approach and a central server to coordinate some aspects of conflicts and updates.

Other things like tree re-ordering in the document, undo/redo behaviors, are resolved with domain specific desired implementations. Additionally, Figma side-steps the entire realtime text interleaving/merging issue due to the fact that the text content of a text element is just another property on an object. As such, changes in this system still follow the LWW model they have gone with.

Additionally, they go over the Fractional Indexing approach that looks very much like the approach seen in Logoot/LSEQ.

Given that you have no record of tombstones (like in the case of Logoot/LSEQ) then you run into the problem of interleaving edits on merge. However, Figma can make this trade-off due to the fact that it is a design tool not necessarily centered around realtime text editing.

Known CRDT Types

At the end of the day, what we are ultimately working with is a set of shared data structures. We need a way to represent our model of interaction / application through the structures that help provide us with the mathematical guarantees and trade-offs all mentioned above. Some of the known types include:

-

G-Set: Grow-Only Set

A set which only allows adds. An element, once added, cannot be removed. Merger of two sets is a union. Operations or complete state merges can utilize this.

-

2P-Set (Two-Phase Set)

Two G-Sets are combined to create a 2P-Set. With the addition of a remove set (tombstone set), elements can be added and removed. Once removed, an element cannot be re-added; that is, once an element e is in the tombstone set, lookups will not return true for that element. 2P-Set uses remove wins so remove takes precedence over add.

-

LWW-Element-Set (Last Write Wins Element Set)

Similar to 2P-Set in that it has an add set and remove set, with a timestamp for each element. Elements added are inserted to add set withwh a timestamp, and removes are added to the remove set with a timestamp.

An element is a member if it is in the add set AND (not in the remove set or in the remove set but with an earlier timestamp than the one in the add set).

Merging is a union of the add sets and union of remove sets. When timestamps are equal, bias can be towards either add or remove.

Advantage over 2P-Set is that elements can be reinserted after removal.

Note on LWW Sets + Garbage Collection

There is a trick that Roshi (a distributed LWW-Set cluster built on top of Redis) that you can add which is garbage collecting on inserts. The trick is to garbage collect whatever item is in the existing add set or remove set depending on the incoming timestamp.

When inserting an element E to the logical set S, check if E is already in the add set A or the remove set R. If so, check the existing timestamp. If the existing timestamp is lower than the incoming timestamp, the write succeeds: remove the existing (element, timestamp) tuple from whichever set it was found in, and add the incoming (element, timestamp) tuple to the add set A. If the existing timestamp is higher than the incoming timestamp, the write is a no-op.

- OR-Set (Observed-Remove Set) > Similar to LWW-Element-Set except uses tags instead of timestamps. For each element in the set, a list of add-tags and a list of remove-tags are maintained. Insertions are done by generating a unique tag and added to the add-tag list for the element. Elements are removed by having all the tags in the element's add-tag list added to the element's remove tag set (tombstone list). > Merging is done by the union of the add-tag list for each element, and the union of remove-tag lists for each element. > An element is a member if the element's add tag list - remove tag list is nonempty.

Sequence CRDTs

Ordered sequence, list, or even trees are considered part of the family of sequence CRDT implementations. There are a number of algorithms here that are typically used in collaborative editors as an alternative to Operational Transforms. Among the papers include:

-

Seminal work for CRDT beginnings in 2006 assigning every character a unique identifier. WOOT also represents text as a directed acyclic graph of characters - referencing left and right neighbors at insertion. Order of identifiers resolves between concurrent insertions to the same location. Deletions are marked as tombstones. Overhead in metadata made this implementation impractical however. Worth reading about though!

-

Logoot/LSEQ does not store tombstone deletions and instead takes an approach with fractional / unbounded divisible indexing. This, as discussed earlier, can cause issues with interleaving edits so it becomes impractical to guarantee proper sane convergence with concurrent operations.

-

Widely considered to be one of the fastest CRDT implementations. Utilizes a timestamped insertion tree and references hash table lookups for character lookups. Causal trees are a similar approach (named CT but in RGA it's called a timestamped insertion tree). In any case, CT/RGA algorithms have been proven to use the same algorithm

-

Similar non-academic implementation with optimizations and tweaks - based on Logoot/LSEQ.

-

Takes a unique approach by defining rules and behaviors to ensure conflicts are resolved by following the operational constraints laid out in the paper. This includes defining an abstraction of what a type and its operations should look like while building on a simple linked list data structure.

Paper outlines definitions, assumptions, and describing convergence in addition to extensible data types with later examples in visual graphs.

When implemented as in YJS, it outperforms RGA and looks to be the fastest and lower space complexity in a number of benchmarks -

Chronofold is a replicated data structure for versioned text. It is designed for use in collaborative editors and revision control systems. Past models of this kind either retrofitted local linear orders to a distributed system (the OT approach) or employed distributed data models locally (the CRDT approach). That caused either extreme fragility in a distributed setting or egregious overheads in local use. Overall, that local/distributed impedance mismatch is cognitively taxing and causes lots of complexity. We solve that by using subjective linear orders locally at each replica, while inter-replica communication uses a distributed model. A separate translation layer insulates local data structures from the distributed environment. We modify the Lamport timestamping scheme to make that translation as trivial as possible. We believe our approach has applications beyond the domain of collaborative editing.

Conclusion

There is a lot of literature out there. Having spent the time to look through these solutions the best one I've come across so far is YJS. I interacted for a bit with the author over twitter and the author has a series of benchmarks designed around actual real-world editing/conflicts and other specific scenarios that are ideal for comparing implementations.

Even still, these solutions are not a catch all and they all have pitfalls and bottlenecks/edge cases that haven't been fully sorted out. Splicing for instance remains a problem in CRDT and there doesn't seem to be a decent solution for it just yet.

In any case, I learned quite a bit and hopefully you did/will to!

Cheers! 🍻

For additional resources on CRDTs:

- Data Laced with History

- Understanding Lamport Timestamps

- YJS: P2P Shared Data Types

- Introduction to Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types

If you liked this article and are so inclined, give me a like and a follow. Also check out my twitter for similar and other updates!

Thanks again!

Top comments (0)