Running a graphical application via a Docker container sounds awesome. Take the relatively larger complexity of a graphical app, encapsulate all of the brittle graphical compilation requirements, and serve a consistent experience regardless of your users' actual hardware. The epitome of the greatness that is containerized applications.

However, I have not seen great recommendations online on how to do this. I have seen many examples of GUI Docker images requiring --privileged or other capabilities to be passed to the container, have seen weird graphical hacks such as running a VNC or SSH server inside the container and exposing the application through that, or running the application inside the container as root. We can do better!

I will show you how to configure your graphical Docker image securely using my PgModeler image as an example: https://github.com/artis3n/pgmodeler-container. Understanding how to secure a Docker container requires understanding the underlying Linux behaviors taking place so we will discuss them in-depth. However, the result is a handful of extra lines to your Dockerfile and two volumes passed during docker run.

If you are just here for the Docker command, here it is:

XAUTHORITY=$(xauth info | grep "Authority file" | awk '{ print $3 }')

docker run --rm --cap-drop=all \

-e DISPLAY \

-v /tmp/.X11-unix:/tmp/.X11-unix:ro \

-v $XAUTHORITY:/home/modeler/.Xauthority:ro \

-v /persistent/local/directory/for/project:/app/savedwork \

ghcr.io/artis3n/pgmodeler:latest

The rest of the article will explain everything happening in this simple, secure command.

PgModeler is a tool to visually develop and maintain PostgreSQL schemas. It is a QT-based application with relatively involved compilation instructions if you are building from source. PgModeler has a GPL-3.0 license and allows you to compile it from source for free; pre-compiled binaries are available for a modest fee. I have not contributed to the PgModeler project, but I did create this Docker container to easily use it.

My goals for this container are:

- Non-privileged user

- PGModeler will run as the

modeleruser, which does not have sudo privileges inside the container.

- PGModeler will run as the

- No host capabilities granted

- We must grant access to our host's X server to draw an application on the screen. For this bullet, I am looking at the Linux kernel capabilities and enforcing that none are used.

- Simple to use

- It should take 1-2 minutes (including

docker pulltime) for an end-user to get started with this container. No complicated file modifications or terminal configuration.

- It should take 1-2 minutes (including

Why care about a non-privileged user inside a container?

There is an argument to make that using a non-root user inside a Docker container is not required. Docker documents the limited functionality of the root user (by which I mean uid=0) inside a container.

“root” within a container has much less privileges than the real “root”...

This doesn’t affect regular web apps, but reduces the vectors of attack by malicious users considerably.

By default Docker drops all capabilities except those needed, an allowlist instead of a denylist approach.

The argument in favor of just using root inside the container - which is the default - is that user uid=0 is already pretty limited inside the container. Only by misconfiguring the kernel capabilities granted to the container can you cause a security issue when running as root inside the container.

I disagree with the idea that project maintainers do not need to concern themselves with the possibility of end-user misconfiguration, especially with a technically complex topic like containerization. To be clear, I hear this argument from people discussing Docker, not from Docker's official documentation or representatives. However, I do not find the argument "it is only a problem if you misconfigure it, now here are a bunch of choices make sure you don't pick the wrong ones" persuasive. Similar to technical experts' complaints against JWTs and PGP - if the standard allows for common implementation errors, the fault lies with the standard, not with the individual implementations. Additionally, running as uid=0 inside a container still leaves you vulnerable to kernel CVEs or other novel container escapes. This is not necessarily something you need to concern yourself with on a personal project, but it is quite important in enterprise production and should be treated as a best practice for personal containers as well.

If you are running as uid=0 inside the container and grant some level of access to the host, you are uid=0 to the host as well. What this means depends on the exact configuration. You may misconfigure a Docker component - unless your code never produces bugs, in which case I want to give you a Captcha check. The misconfiguration may be as tame as passing in a volume that you didn't intend to passing a kernel capability or, please say it isn't so, passing the Docker socket from the host into the container. These may allow a process to break out of the Docker container.

But even if you don't misconfigure a container, running as uid=0 inside the container may still leave you vulnerable. One of the most famous recent Docker exploits is CVE-2019-5736, a container escape leveraging runc. The exploit is well explained by Palo Alto Network's Unit 42 here. RunC is a container runtime originally developed as part of Docker and later extracted out as a separate open-source tool and library.

High level” container runtimes like Docker will normally implement functionalities such as image creation and management and will use runC to handle tasks related to running containers – creating a container, attaching a process to an existing container (docker exec) and so on.

An attacker with root access in the container can then use /proc/[runc-pid]/exe as a reference to the runC binary on the host and overwrite it.

Root access in the container is required to perform this attack as the runC binary is owned by root.

The next time runC is executed, the attacker will achieve code execution on the host.

Since runC is normally run as root (e.g. by the Docker daemon), the attacker will gain root access on the host.

So, without doing anything wrong, if your container's user ran as uid=0, you would be vulnerable and a process could break out of the container. If you were a non-root user, the CVE could not have been exploited. For a development or personal project, these things are perhaps not something you need to care about. You are generally running your own code inside your container on a personal host. However, I think it is important to understand the reasoning here. Especially for production or externally-accessible resources, your containerized code should be running as a non-root process. I recommend always doing it because it isn't much additional effort. It does require you to understand what you want your container to be doing because you must explicitly grant your non-root user read/write access to the appropriate files in the container. I consider that a side benefit of this process - a better understanding of your code.

Configuring a non-privileged user

The requirements to set up a non-privileged user are highly dependent on what you need the user to do inside your container. In my case, I need my modeler user to be able to run PgModeler. The PgModeler source code will be copied to /pgmodeler and I will compile it to /app. Thus, modeler just needs to own the /app directory to run PgModeler. In fact I leverage a multi-stage build to reduce the image bloat and only copy in the /app directory after compiling it in the intermediate layer.

The USER Dockerfile command will set the username (or UID / GID) for any subsequent RUN, CMD, or ENTRYPOINT instructions. So my steps are:

- As root, copy the PgModeler source code onto the container

- Create the

modeleruser - Compile PgModeler and ensure

modelerhas permissions on the/appdirectory - Assume

modeleruser withUSERbefore theENTRYPOINT

I copy over the source code from two submodules in my repo:

COPY ./pgmodeler /pgmodeler

COPY ./plugins /pgmodeler/plugins

I compile the application in one RUN command.

WORKDIR /pgmodeler

RUN mkdir /app \

&& mkdir /app/savedwork \

&& "$QMAKE_PATH" -version \

&& pkg-config libpq --cflags --libs \

&& "$QMAKE_PATH" -r CONFIG+=release \

PREFIX="$INSTALLATION_ROOT" \

BINDIR="$INSTALLATION_ROOT" \

PRIVATEBINDIR="$INSTALLATION_ROOT" \

PRIVATELIBDIR="$INSTALLATION_ROOT/lib" \

pgmodeler.pro \

&& make \

&& make install

Now in the next stage of the build, I copy the /app directory and create a non-root modeler user. I grant that user permissions on the /app directory.

COPY --from=compiler /app /app

RUN groupadd -g 1000 modeler \

&& useradd -m -u 1000 -g modeler modeler \

&& chown -R modeler:modeler /app

Finally, I set my image to assume the modeler user for the ENTRYPOINT.

USER modeler

WORKDIR /app

ENV QT_X11_NO_MITSHM=1

ENV QT_GRAPHICSSYSTEM=native

ENTRYPOINT ["/app/pgmodeler"]

Let's talk about the 1000:1000 UID:GID.

I want the non-privileged user to be able to write files to a mounted volume at /app/savedwork inside the container. This will allow for project file persistence between invocations of the container, allowing us to save work to a directory on the host file system. To do this, the container user must have the same UID and GID as the host user who owns the directory on the host. What do I mean? Let's look at the Documents folder on my host file system.

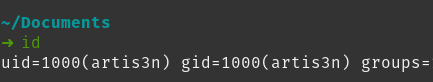

My host's username and group is artis3n and I can see with the id command that my user ID (UID) and group ID (GID) are both 1000.

These days on Linux systems, new users are created starting at id 1000. This default is defined in /etc/login.defs.

This means it is extremely likely that every end-user of my container will have 1000:1000 UID:GID. This matters because when mounting a volume to a Docker container, Docker passes the host file system permissions onto the mounted volume path. So if we mounted ~/Documents on the host to /app/savedwork inside the container, the savedwork directory will have permissions 0755 1000:1000. Only the owner, user ID 1000, will have write permissions to the directory. Group and world will only get read and execute.

We could modify the permissions on our host file system to grant world-writable permissions to the directory (0757 or 0777), but that is strongly not recommended. Instead, by ensuring our internal container user's UID matches our host's UID, we can assume the existing 1000:1000 ownership of the directory and write files to the volume transparently.

My base FROM image is ubuntu:20.04, so I can check and see that the same 1000 default is set as well. We can also see that if I run useradd and create a user, that user is given 1000:1000 UID:GID.

However, I don't want to rely on that default. I want to be explicit in my container and avoid implicit failures. It is a simple process to explicitly declare what UID and GID you want when creating a new user and group. This is where the -g and -u flags come into play in the groupadd and useradd commands, respectively.

RUN groupadd -g 1000 modeler \

&& useradd -m -l -u 1000 -g modeler modeler

We can see with -g and -u that we explicitly assign the GID and UID for our new user. This ensures that we will always have 1000:1000, matching our user on the real host.

What if our host user isn't running the default UID:GID?

What if our host user isn't 1000:1000? Given that we explicitly give modeler UID and GID of 1000, we will need to keep the container UID as 1000 for modeler to run /app/pgmodeler. An alternative is to rebuild the container with group/world-writable permissions inside the container to the necessary files for pgmodeler to run. This is a legitimate path forward and preferred to changing directory or file permissions on the host, but I have not elected to do that in my container at this time. For your container, you may want to consider that.

Regardless, we can pass in different UID and GID assignments to the Docker user when starting a container. For example, if our host user is UID/GID 1001, we can tell Docker to start the container and add the container user to the 1001 group.

This will allow us to write files to the persistence volume while allowing modeler to still run pgmodeler. Note that entering the container throws an error because group 1001 doesn't exist inside the container, but we can see with id that our modeler user's groups have changed. If group 1001 on the host owns the directory volume mounted to /app/savedwork and has write permissions, the container will still run and we will be able to save files to our mounted volume.

If I need to change the user's UID, I can do so with -u.

I can change both the UID and GID (in UID:GID format) or just the UID. This overwrites the UID or GID for the user in the container as opposed to appending a new group with --group-add.

This is it! I have a non-root user running pgmodeler inside the container and can modify the user inside the container to match requirements on the host to write files for project persistence.

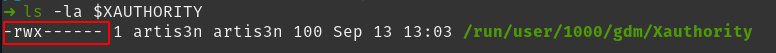

Note on Xauthority and UID

When discussing how to modify the container user with -u UID:GID in the docker run command, the most important consideration for my project is the owner of the Xauthority file. We haven't reached this section of the article yet, but this is a file granting a user permission to access the host's X server. We pass this file into the container so the container user must be able to read this file. However, this file is commonly only readable by the host owner.

If an end-user tries to use my container and isn't UID 1000 on their host, they will fail to access their host X server and pgmodeler will fail to start (because my container will try to read the file as UID 1000). If a user modifies their UID with -u when starting the container, pgmodeler will fail to start because UID 1000 owns all the necessary files inside the container.

The solution is to rebuild the container with world-writable file permissions on the necessary files inside the container for pgmodeler to run. I have opted not to make those changes at this time until I get a GitHub issue from an end-user hitting this problem. I don't need to over-engineer the container if the issue does not present itself! However, for your graphical containers, this is an important point to keep in mind.

An alternative but less-recommended solution would be to enable any localhost connection access to your X server with xhost +local:. This is not recommended and we will shortly explore why that is, but it would allow a user in the container without the host's UID access to the host's X server.

Passing the host display to the container

X server enters the chat.

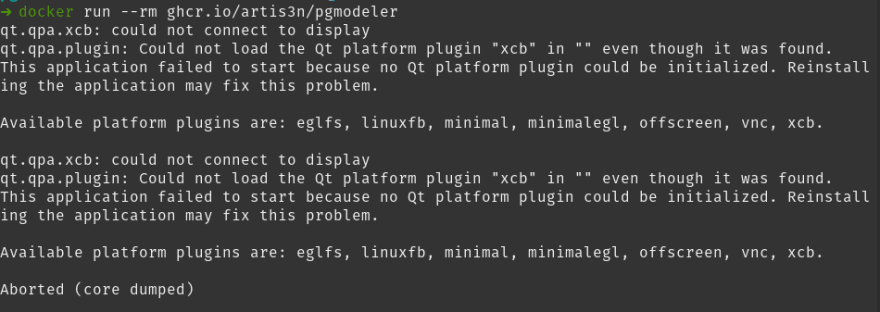

We have compiled the graphical application in the image and created the non-root user. We are ready to run the container. It needs access to draw an application on our host's display. Simply running the container results in a could not connect to display error.

How do we grant access to the display? This is done by granting the container access to the host's X server.

An X server is a program in the X Window System that runs on local machines (i.e., the computers used directly by users)

and handles all access to the graphics cards, display screens and input devices (typically a keyboard and mouse) on those computers.

Passing access to your display into the Docker container requires mounting either 1 or 2 volumes in read-only format. -v is a standard way of doing this, although --mount is now the Docker-recommended approach for passing in a volume. You include either flag during a docker run invocation. The syntax for -v is very particular and is one of the reasons why Docker recommends the more verbose (albeit initially confusing) --mount syntax. I still find -v simpler, perhaps because I am already familiar with the syntax. -v is constructed of 3 parts separated by colons (:).

-v /path/on/host/:/path/on/container:optionalOptions

For example, we use -v /tmp/.X11-unix:/tmp/.X11-unix:ro to pass the X server socket into the Docker container. /tmp/.X11-unix is the Unix domain socket path for the X server socket on Linux and OSX systems. The GUI app needs access to this socket to draw the app on the screen.

However, passing this volume to the container is still not sufficient. We again get a could not connect to display error and a core dump.

This is because of X server's access control. This access control is governed by two methods: xhost and xauth.

xhost sets global policy rules for the X server. For example, we can run xhost +local: to allow any localhost connection access to our host's X server. This is not recommended. However, this would work in getting our container running. We can see that passing in our $DISPLAY with -e DISPLAY and allowing local connections with xhost enables the application to run.

xhost allows us to add or delete hostnames or usernames to the allowlist of things allowed to make connections to the X server. The smallest access we can grant is localhost access from the host user (in my case, artis3n). However, this grants access to any process running locally. There is no way to restrict access with xhost to just the single process (the pgmodeler Docker container).

This is where xauth comes in. xauth grants what we'll charitably call authentication for the X server. xauth enables a so-called "magic cookie" that you can share between hosts and processes. When the container wants access to the display, it presents this magic cookie to the X server and is granted access. This allows us to grant access to just our Docker container. Any other process running locally is still restricted from accessing the X server.

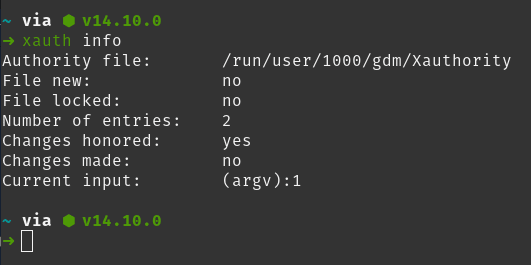

xauth is running by default on any system with an X server. To grant our container access to the magic cookie, we need to find where our system has written the file and then pass in that file to the Unix default location: $HOME/.Xauthority. In our case, that would be /home/modeler/.Xauthority.

We can discover the location of our .Xauthority file with the command xauth info.

We can use the following command to extract the absolute path of our .Xauthority file on any system.

XAUTHORITY=$(xauth info | grep "Authority file" | awk '{ print $3 }')

Now we pass in that volume to the container (read-only, :ro) and see that the container can display the GUI without needing to disable xhost controls.

A note about X11 risks

In the above examples, the container will have full access to the host's X server, either by disabling restrictions with xhost or by granting access through the xauth cookie. What is the risk? Well, for one, the X server must have access to draw on our screen because it creates the graphical application. This means that a malicious application running in the container (having been granted X server access) can take a screenshot of our screen whenever it wants.

But, wait, that's not all! The X server also has access to the clipboard and input devices such as the keyboard and mouse because it needs to know how to translate movement, typing, and copy+paste actions from the host to the GUI app. So, if I run a third-party product inside my container (such as PgModeler), passing in the X11 socket can give that code the ability to log my keystrokes, manipulate my mouse movements, and read data copied into my clipboard. This article presents some proof-of-concept exploits hijacking an X11 socket for nefarious ends inside a Docker image. In particular, the "enable caps lock every 20 minutes" example would drive me crazy.

X11 wasn't designed for security, so there is no way to restrict these capabilities if you grant something access to your X server. The best we can do is limit the number of things that can access the X server. This means leaving xhost alone and passing the xauth cookie to a container whose code you trust. Don't pass the X server socket into a random 3rd party container you have not audited!

To cap-drop or not to cap-drop

The final modification I will make to my docker run command is to drop all Linux kernel capabilities. As documented in Docker's security section, Docker grants a container a restricted set of kernel capabilities.

These defaults are typically fine to leave as-is. In a security-sensitive production container, however, it is worth dropping all kernel capabilities and seeing if the container still works without issue. And if the container does break, incrementally adding single capabilities until the necessary one has been identified.

For my PgModeler container use case, I can leave the default capabilities alone. However, my container also runs PgModeler fine after removing all kernel capabilities. So, let's do that! --cap-add is used to add individual kernel capabilities to the Docker container. --cap-drop is used to drop individual capabilities. To drop all of them, we can use --cap-drop=all.

Wrap-up

The final Docker command to run the image becomes:

XAUTHORITY=$(xauth info | grep "Authority file" | awk '{ print $3 }')

docker run --rm --cap-drop=all \

-e DISPLAY \

-v /tmp/.X11-unix:/tmp/.X11-unix:ro \

-v $XAUTHORITY:/home/modeler/.Xauthority:ro \

-v /persistent/local/directory/for/project:/app/savedwork \

ghcr.io/artis3n/pgmodeler:latest

Hopefully, you now understand every option being set here. The final volume mapping to /app/savedwork in the container is used for project persistence. We can save files in PgModeler to the /app/savedwork directory and they will be written to the host file system at whatever path the end-user chooses to mount.

If you are hesitant to allow X server access to a container, an interesting project to explore is x11docker. The gist of that project is to run a second X server with its own authentication cookies. Docker containers get access to the new X server and are segregated from display :0 on the host. This would prevent them from accessing your main display, although I am not sure how it affects the keyboard, mouse, and clipboard. Head over to that project and ask!

You can view all the code for my PgModeler container at the repository: https://github.com/artis3n/pgmodeler-container.

If you need a Postgres schema visualization tool, try PgModeler through my container, either from the GitHub Container Registry or from Docker Hub!

docker pull ghcr.io/artis3n/pgmodeler:latest

docker pull artis3n/pgmodeler:latest

Top comments (0)