A look into reducing bug leakages in microservices shared across multiple development teams

I work in a software organization where change is frequent, to say the least. As a developer and part of a larger team building an e-commerce platform, we’ve more or less adapted to frequent changes in project management, development methodologies, testing ideologies and of course now (given the current global pandemic), remote collaboration. This behaviour-driven test strategy was developed within our team as a way to reduce bug leakages in mission-critical systems as our organization grew to include off-shore development teams (with product owners representing different customer interests)—and in order to ensure that the quality of the systems would not be affected by evolving engineering philosophies over the years.

Background

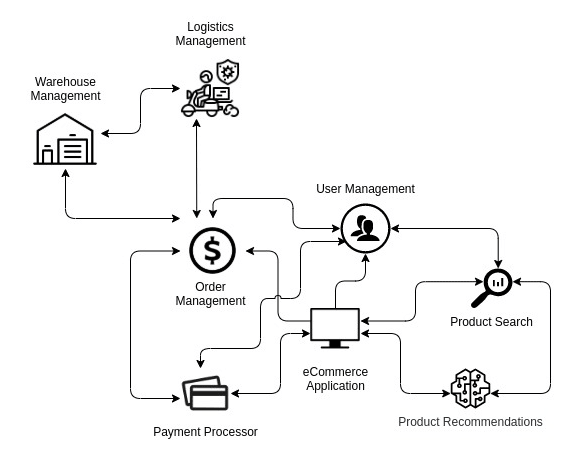

When working with an enterprise application powered by microservices you can end up with a lot of sub-systems designed to handle different parts of a user's experience.

In an e-commerce setting these microservices might be scoped to manage users, orders, payment processing, product recommendations, product search, etc. leading to a lot of moving parts under the hood. Depending on the design of the system, each microservice might consume a bunch of others based on a predefined flow to complete a user action.

An example would be a user wanting to know the delivery ETA of an order while in the order details page. In order to generate an ETA for the delivery (as per the diagram above), the delivery microservice would need to fetch the order stored with the order management service, cross-check its location with the warehouse and logistics services, fetch driver information and estimate a delivery time depending on a GPS marker. That’s four different sub-systems working in unison to populate a label on the user’s screen with the delivery information of an order.

The Problem

As and when your product grows, so will the requirements of your target users and in extension the demands of your product owner. This is when our software organization started to expand and grow, breaking off into smaller specialized business units (or verticals) focused on developing a part of a users experience like tracking the delivery of an order rather than taking tickets from a common project backlog in a round-robin manner.

When you have teams working on different aspects of a customer’s experience you tend to get new features that require changes across many sub-systems — and having many developers building multiple features across the entire stack at the same time is a really big risk if you don’t have a proper test suite.

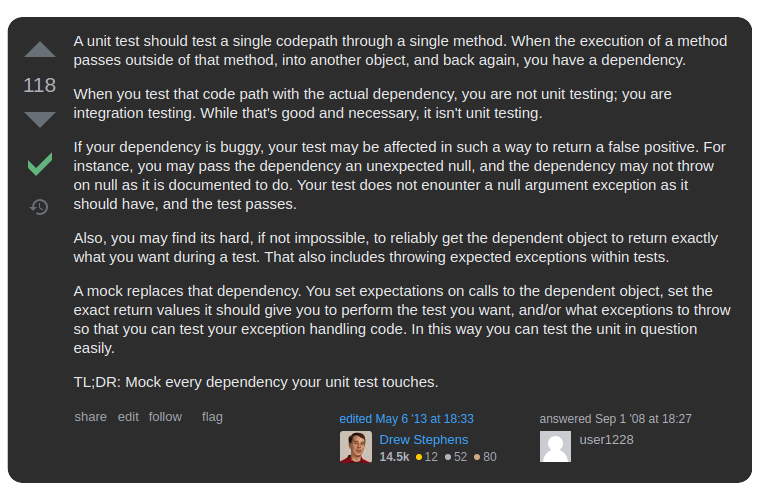

In a unit test suite, the problem with mocking every dependency is that if you change a method’s functionality, and other methods in its call hierarchy have already mocked it, you won’t know if any functionality different to your own has been broken. This becomes a significant problem for developers (both new and old alike) since it’s difficult to comprehend the entire affected scope of a changeset.

You might end up breaking an already working flow belonging to a team that handles order placement when implementing a feature related to order tracking in the order management service.

But isn’t that why we have Integration Tests?

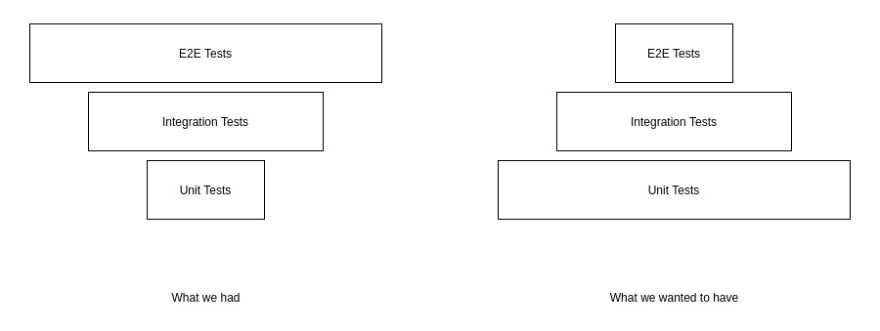

True. But once you’ve included tests for every edge-case, bug, and race-condition in addition to the existing cases in your integration test suite your test pyramid is going to look a lot like the one we had.

Although we had more than 80% coverage in all our unit test suites the reason it looks more like an ice-cream cone than a pyramid was because we added on so many integration and E2E test cases that towards the end some integration suites would take over 60 minutes to complete — that’s 1 hour wasted by a developer waiting to know if their code change broke another feature in the service — and with the suite running on a CI server it’s still going to be difficult to understand the entire scope of the broken tests and narrow down the impacted area to debug the faulty logic.

The Solution

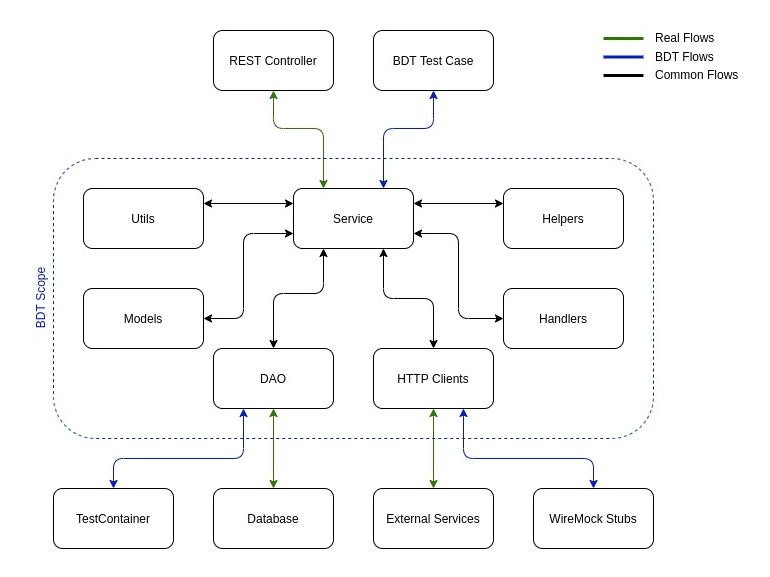

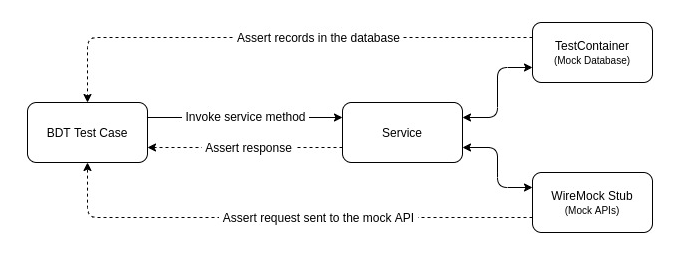

We came up with an integration test suite that could be used to test entire API flows within a microservice while co-existing with unit tests, which would be executed automatically along with the unit test suite. A test would be executed from the service method that the REST controller uses while mocking only the external database and API calls.

As shown above, we only mock anything outside the control of the service i.e. the database (using TestContainers) and external API calls (using WireMock). Unlike normal integration tests, this allows us to assert not only the response object sent from the service but also the state of the database as well as the API requests that were sent to the stubs. We can also configure the database and stubs to return different results to the service in order to recreate successful, buggy, and edgy flows in order to assert the correct behaviour during those scenarios.

Since this strategy allows you to control and assert all the entry and exit points of your service, you have the ability to write test cases to verify the exact behaviour of the relevant API endpoint.

Naming Conventions

This is where BDT gets its name. Remember that you are testing a complete flow in the viewpoint of a downstream service. A test case for the previous example which returns the delivery ETA of an order (GET /order/:orderId/location) where you also need to simulate the failure of an upstream service would look like the one shown below.

Here the name of the test case should represent the expectation of the service that would be consuming that method via an API invocation as per the contract. We also try to make sure that the name clearly identifies the test scope so that a developer would be able to look at a test case and immediately know what is expected.

The Results

Since these new tests execute along with the existing unit tests, and since the database and external APIs are mocked, we’ve seen around 1500 test cases completing within a couple of minutes — that’s around 95% faster than what our previous integration test suite running on a CI server would have taken while more or less covering the same test cases.

While we didn’t completely flip around our test ice-cream cone, we were able to grow our unit test layer to include many test cases that would otherwise have required real database and third-party service calls, leaving our integration and E2E test suites to cover only the most vital flows (the happy and bad paths).

Now if a developer working from anywhere in the world was building a feature or fixing a bug and inadvertently broke any established API behaviours, they would see the exact impact of the change in their local environment itself and fix it without waiting for a quality gate failure or a bug reported in a cloud environment — which significantly reduces the number of bug leakages as well as the time to completely release a ticket.

Disclaimer: The testing strategy described here is not meant to be a replacement for unit tests.

Top comments (0)