The other day I was sick and bored. With nothing better to do, I spent a day building ArpChat, a slightly-cursed chat app entirely running on ARP.

Several people have asked me how ArpChat works behind the scenes, so I thought I would write a quick post. While building it wasn't particularly novel for me, you might learn something new if you're new to networking!

A quick note: when I say "IP" throughout this article, I'm referring to IPv4. Near the end, I'll go over IPv6 and its position in the networking stack.

Quick Primer: The OSI Model & Why We Need ARP

Computer-to-computer communication is tremendously complicated; you can get a degree in this stuff! HTTP, the protocol you're using to access this website, runs on another protocol called TCP. TCP, in turn, builds upon IP, the general standard for sending data over the internet. IP itself is many layers of abstraction above the 1s and 0s transmitted over a physical medium.

Historically, computer scientists have organized all these "layers" of communication using a system known as the OSI model:

- At the lowest level is the physical layer; computers need to transmit binary data in the real world somehow! Typically, a chip in your computer will send electricity over an ethernet cable or transmit radio waves through the air.

- Above this is the data link layer, which makes sure that the signals that network cards send to each other will reach the right physical destination.

- On wired connections, ethernet switches work on the data link layer to retransmit incoming signals on the right output cable. If you have a home router, it probably has a built-in switch.

- Wireless access points serve to allow devices to connect to a wired network through radio waves.

- One abstraction up from the data link layer is the network layer. This creates a conceptual "network" of nodes (devices) by providing a convenient way to route messages. IP, the internet protocol, is by far the most common standard for the network layer.

The main identifier for nodes on the network layer is an IP address. IP addresses can change, and aren't assigned to any specific piece of hardware— if you switch the network your computer is on, your IP address will probably change as well. Meanwhile, MAC addresses are the main identifier on the data link layer. They're assigned to a specific network chip in a computer and don't change.

When sending a message on the network layer, your computer needs to drop down to the data link layer to make sure packets reach the right device. That means there must be a way to find a MAC address for a given IP address— we call this protocol ARP, an initialism for address resolution protocol.

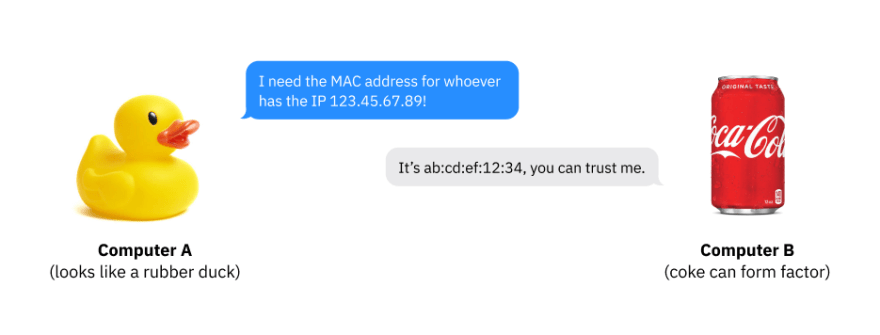

With ARP, Computer A can send a request to every computer in the area with an IP address. If another computer recognizes the IP as its own, it can respond with the corresponding MAC address. When Computer A receives the response, it knows how to send its original message along the data link layer.

Now, what if we sent nonsense instead? Well, the packet will still go through but every computer on the network will ignore it. Imagine the things one could do...

How Does ArpChat Abuse ARP?

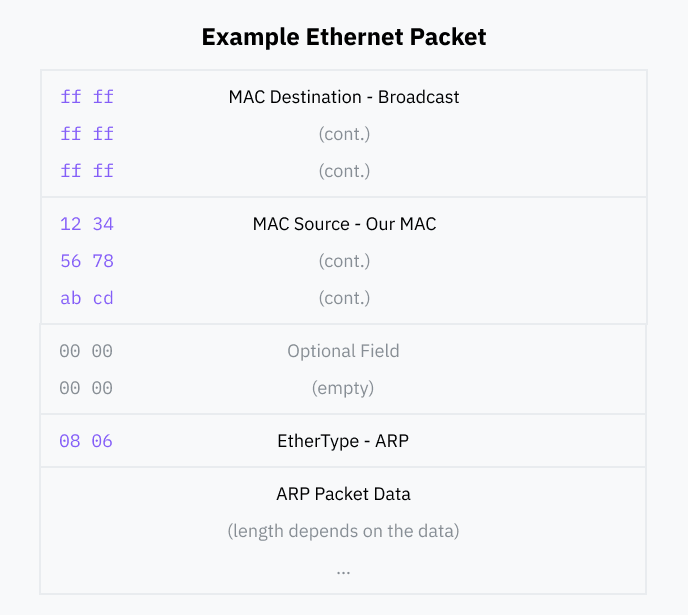

ARP is a "layer 3" protocol. This means a layer 2 (physical layer) packet has to wrap every ARP packet; we'll include our data in an "ethernet" packet format designed for both Wi-Fi and wired ethernet.

Our ethernet packet will be super simple. First, we include the destination MAC address— since we want to send our packet to everyone, this will be a special value called the broadcast address, ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff. Switches should forward broadcast packets to every device they know about.

For the remaining fields, we include our source MAC address and specify that the packet contained is of the ARP EtherType. At the end, we append our ARP data. We can leave the remaining optional fields empty.

ARP Packet

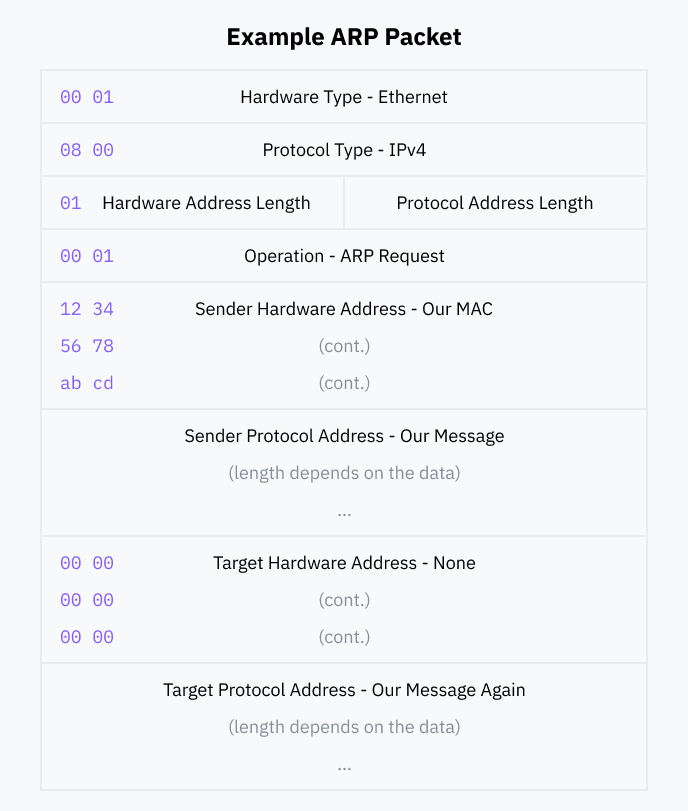

We'll be sending what's known as a gratuitous ARP packet. When changing IPs or joining a new network, devices will often announce their presence to other devices on the network; due to their nature as good-faith announcements, gratuitous ARP packets tend to have high deliverability.

The standard requires that ARP packets have the following fields:

- Hardware and Protocol Type: the kind of data link and network layer our ARP message relates to. In our case, these are ethernet and IPv4 respectively.

- Hardware Address Length: we're complying with this aspect of ARP so we'll specify the length of a MAC address, 6 bytes.

- Protocol Address Length: this would normally be 4 bytes, the length of an IP address. Instead, we're going to deviate from "proper" ARP— since we want to send more information than just an IP address, we'll specify the length of our data instead.

- Operation: this designates the packet as either request or a reply. According to one convention, gratuitous ARP packets are requests.

- We'll fill the Sender Hardware Address with our MAC address, and the Sender Protocol Address with our data.

- For the Target Hardware Address we'll specify an all-zero MAC address,

00:00:00:00:00:00, and we'll include a duplicate of our data in the last field, Target Protocol Address. These are both conventions of gratuitous ARP messages.

Now we can pull out the good ol' Rust compiler and write a bit of networking code to send arbitrary data over ARP!

Building a Layer on Top of ARP

Now that we can send stuff to other devices on the network, how do we make something useful? The first limitation is that the Protocol Address Length has to fit in one byte. Since the largest number that can fit in a byte is 255, this restricts the length of our messages.

Any grade-schooler would know that creating a rudimentary transport protocol on top of ARP is the necessary next step, so that's exactly what I did!

"Protocol" & Chunking

Every packet we send over ARP first consists of a prefix— in ArpChat, this is uwu. This is convenient for ArpChat receivers, as they can cheaply discard ARP data that doesn't start with this prefix.

Next, we'll include three bytes: a tag, a sequence number, and a total count. The tag identifies the kind of data; in a chat app, this could be a text message or a status update.

To enable sending messages longer than 255 bytes, we can split them up into smaller chunks. The count field specifies the total number of chunks, and the sequence contains the position of one chunk within the total number of chunks. Receivers can use these two fields to reconstruct a full message from its separately transmitted parts.

Right before passing the chunk data, we include a unique identifier that varies between each message. The first of two purposes is for deduplication: we ignore a packet if it's received twice by maintaining a ringbuffer of recently received identifiers. The second purpose is to provide a simple key for identifying message chunks as part of a group.

Internet Fame™

With a bit more Rust code, I created a nice abstraction over this system that automatically chunks messages and deduplicates and gathers them on the receiving side.

Using Cursive, I built a terminal user interface and implemented a small chat app over ARP. On the second day that I was sick, I did some polishing and implemented a presence system for requesting who's online and gratuitously broadcasting when you connect or disconnect. This is, in an ironic fashion, close to ARP itself— one could run ARP on top of ARP for some true ARPception!

The internet somehow found ArpChat's GitHub repository and it gained some popularity, reaching the top 6 on GitHub Trending with 300 stars in one day! I never expected that a tiny project I made while I was sick would garner so much attention, but here we are. With the exposure that comes from 1.1k new GitHub stars, I even ended up making a couple of new friends.

I'm basically done with this project, but you may try out the latest release if you feel so inclined.

Security with ARP, IPv6, and NDP

As you might've noticed, ARP feels a bit flimsy. Any device can claim association with a certain IP address and everyone else on the network will believe them. When done maliciously, this is well-known in the security world as an ARP spoofing attack. The potential for danger is partially shown by how trivial running ArpChat is!

Meanwhile, the number of devices on the public internet continues to increase as we grow closer and closer to reaching the limit of used IP addresses— there are only so many possible combinations.

The answer to these and other problems is IPv6, a new version of IP with longer addresses, more sophisticated routing, and more modern protocols than IPv4. IPv6 also replaces ARP with a new protocol. NDP, which stands for neighbor discovery protocol, features security-conscious features such as cryptographic message verification, rendering it much better than ARP.

While the world gradually migrates to IPv6 and NDP, ARP is here to stay for years to come. ArpChat and ARP spoofing attacks are staying as well. Maybe an unseen benefit of IPv4 is that you can text your friends or coworkers on even a heavily restricted network! I await the day Verizon rolls out IPv6 to my home.

Technicalities

I simplified a couple of things for the sake of practicality. I believe in accuracy as well, so I'd like to provide some small clarifications. You can also click on linked words throughout the article for in-depth information on the technology I've brought up.

Saying that MAC addresses don't change was a bit of a white lie. Your computer can simulate ("spoof") a different address, and modern operating systems such as macOS are introducing features to randomize your MAC address every time you connect to a new network. These features can help prevent fingerprinting but don't practically change how ARP and the rest of the networking stack works.

I mentioned specifying IPv4 as the Protocol Type for our ARP packets. It turns out that IANA designates two alternate types for "experimental" use, which ArpChat now defaults to for the sake of being nicer to other networking equipment. IPv4 is still a configurable option.

I also described ARP as a layer 3 protocol. There's some contention on this— while I think this is the most accurate and easiest explanation, networking is more nuanced than the OSI model might convey. Some would describe ARP as a level 2 or even level 2.5 protocol. For our purposes, I believe calling it level 3 makes the most sense.

Two minor self-nitpicks: I claimed you're using HTTP on top of TCP to access this website. If your browser (and my server) supports HTTP/3, you might be using QUIC over UDP instead! I also left out a field of the ethernet packet containing a checksum. The networking library I used autogenerates this, and I don't think it's important in an explanation of ARP.

Feel free to email hi@kognise.dev with any questions or corrections, and you're welcome to check out ArpChat's Rust networking code!

Top comments (0)