Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Lambda Execution Model

- Cold and Hot Starts

- Running Locally and Testing

- No Always-On Server to Manage and Pay for

- Implicit High Availability and Transparent Scaling

- Closing Remarks

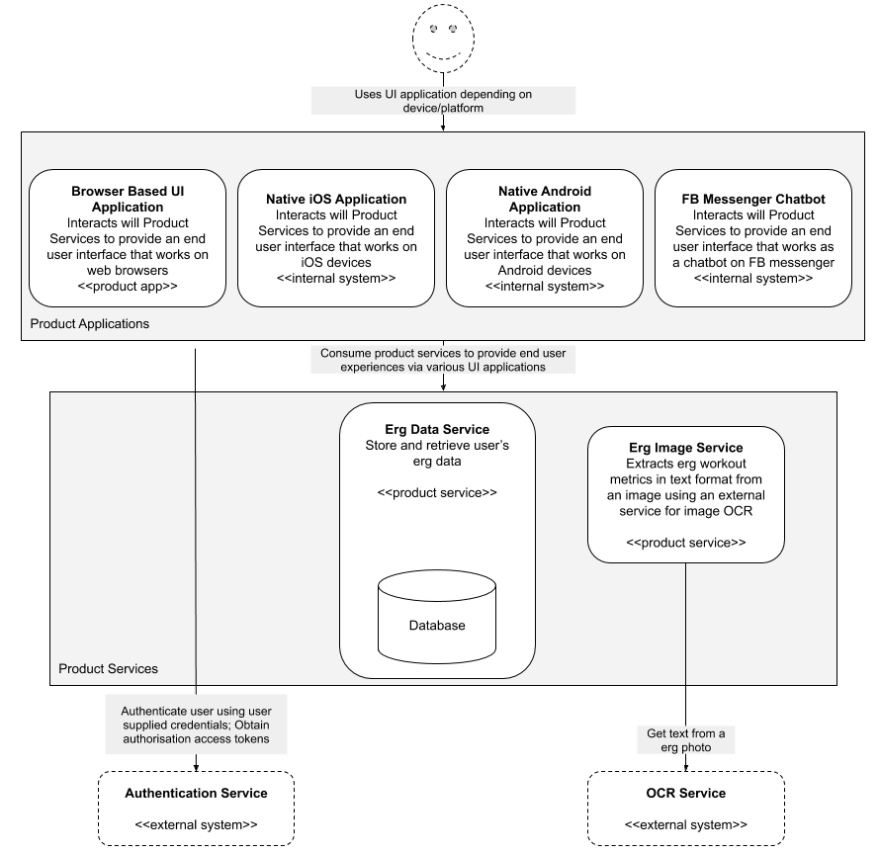

Recently undertook an exercise to build a product comprising of a browser based UI application and a set of backend web services. Below are my scribbles from the exercise focused on comparing PaaS (primarily Heroku) with Serverless cloud services, in context of the applications being built. Before jumping into the thinking behind the choices, a quick look at the high level architecture of the product.

Introduction

PaaS and Serverless are layers of abstraction over traditional Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) capabilities. Compared to PaaS, Serverless is an even higher level of abstraction and allows the service user to delegate even more to the service provider. The higher level of abstraction, while making the service user’s life easier comes with certain constraints that are important for the service user to be aware of.

Serverless compute services are typically referred to as Functions as a Service (FaaS). Using FaaS, we were able to run custom application code for the Erg-Image-Service, without provisioning any servers or container units like Dynos in case of Heroku.

Limits on the amount of time a Serverless function can run before it timesout and the environment terminates may make FaaS unsuitable for certain special usecases (an example I have dealt with in a different product - running a compute intensive genetic optimisation algorithm on a large data set). Until early October 2018, the maximum execution duration per request for AWS Lambda was 5 minutes, but is now 15 minutes. No such limits apply when using PaaS.

Lambda Execution Model

When building and running applications to run on a PaaS, we had to think of ways of making effective use of the compute resources available to our application web server as a whole. For instance, we chose the Reactive Web Spring library and ran the ErgDataService inside a Netty web server so that we could handle as many concurrent requests as possible with a limited number of Dynos in order to keep our Dyno usage and thus the Heroku bill down. Our key reasoning behind the use of a reactive programming library was to get the most of a single Netty server running on a single Dyno. More info on why reactive programming is beneficial, can be found here. Once we had extracted most out of a single Dyno, horizontal scaling technique to provision new Dynos running our application were employed.

In contrast to PaaS, where we were responsible for writing code or utilising java libraries to handle multiple concurrent requests within a single Dyno as efficiently as possible, when using FaaS, our focus on efficiency was at a single request or single function invocation level. How our service scaled to handle multiple concurrent requests via multiple function invocations was handled transparently by the serverless platform. We didn’t have to think about reactive programming and Netty for request concurrency at the Erg-Image-Service level. We didn’t have to write any REST controllers to receive and process incoming requests as the Serverless framework handled the HTTP Request/Response handling for us. The higher level abstraction in the form of a per request execution model provided by AWS Lambda platform allowed us to delegate even more to the service provider and simplified the amount of code we had to write and maintain.

Cold and Hot Starts

In the AWS Lambda execution model, a single function is executed within its own execution environment/context in response to an event such as a request from the API gateway. In the context of our service, the Erg-Image-Service, each time a new request came in from the API gateway the service provider either reused an existing execution environment that was lying around idle or provisioned a new one. But at all times an execution environment was only ever processing a single request.

After an execution environment is provisioned and used to process an event/HTTP request, it lies around for a while (typically around 20 minutes) before being terminated. If a new event is fired before the execution environment is terminated, it reuses it and this is referred to as a “hot-start” of the Lambda execution. If there are no idle execution environments to process an event, the service providers provisions a new one and this is referred to as a “cold-start” of the Lambda execution. Cold-start involves the service provider setting up the execution environment on a container from scratch, deploying our Lambda code to it and starting the Java process etc. This results in cold-starts typically adding a few seconds of latency to the event processing and can be an issue for applications that have a real end-user of the application waiting for the processing to complete. Additionally, if to process an event the function code has to setup database connections to store/retrieve data, the connections have to be setup from scratch in-case of a cold start and patterns such as DB connection pooling don’t help.

A key factor that impacts the cold-start latency is the Lambda function package size. If the application binary deployed to Lambda is heavy, pulls in several dependencies, relies on an embedded server such as Jetty or Netty to be initialised, it all adds up to the cold start time. The official recommendation from AWS for Java based Lambda says that one should prefer simpler frameworks that load quickly and avoid complex dependency injection frameworks such as Spring (AWS Lambda best practices). Even when using a framework such as Spring Boot, it is recommended that unnecessary dependencies such as an embedded server are excluded from the code package gets deployed to Lambda. We thus kept third party library dependencies in the Erg-Image-Service in check and didn’t use Spring framework at all.

Cold starts are not a problem exclusive to Lambdas and affect PaaS too. When a PaaS scales-up the number of containers or VMs to handle the incoming load, the setup time for provisioning a container is as high as it is with FaaS. However, a key difference is that the number of container or execution environment setup events in FaaS can be significantly higher compared to PaaS. A PaaS reuses the same container to handle multiple requests and needs a new one when the existing cluster of containers don’t have enough compute power to handle the extra load. While, a FaaS sets-up may need to setup a new container for each request. The ratio of hot to cold starts in a FaaS environment depends on the traffic pattern. If the traffic patterns are fairly even, say a few requests every minute, it is likely that most Lambda executions would be off a hot-start. However, if there are several spikes in traffic or if the traffic is fairly sporadic, say 1 every ~40 mins (i.e. by the time a new request comes in the previously used container is terminated), we are likely to see several cold-starts.

When using PaaS, there is typically a minimal number of containers ready to server requests in anticipation of traffic even when there is little to no load on the application. With FaaS, if there is a period of inactivity, all containers would be terminated and new ones would be provisioned from scratch when new requests come in.

In summary, while cold-starts exist in the PaaS environment too, they tend to be more noticeable in a FaaS environment. We utilised the WarmUP plugin for the Serverless Framework to keep our lambdas warm.

Running Locally and Testing

Running applications locally while developing as well as in a CI environment was straightforward to do when developing for deployment to a PaaS. We simply ran the Netty server with our application code running in it, anywhere we wanted and we had a server capable of handling HTTP requests to endpoints exposed by our service. While developing the Erg-Image-Service to leverage FaaS, we were able to test the core service logic locally, but didn’t have any easy way to run an end-to-end service that could respond to HTTP requests. This is not to say it wasn’t possible, but would have required additional work via third party libraries such as localstack. This isn’t necessarily a drawback when using serverless platform, but emphasises a different way of thinking and approach when using serverless instead of PaaS. We remained focused on testing code we wrote and didn’t worry too much about HTTP request/response handling which was a capability provided by the platform.

Update: Hadn't come across Serverless Offline when I originally undertook this exercise. Now that I do, I use it for testing and running my AWS Lambda functions locally.

No Always-On Server to Manage and Pay for

In contrast to PaaS, when using a Serverless service, there isn't a concept of an "always-on" server that the service user provisions and pays for. When a user leverages PaaS to provision, say, a database using AWS Relational Database Service (RDS), there is a defined database server with a predefined CPU and storage space made available to the user. Irrespective of the actual usage and load on the database, there is a server process running, ready to serve the service user’s needs. On the other hand, when using a Serverless database, such as AWS DynamoDB, a service user is operating at yet another higher layer of abstraction. The user doesn't provision a database server, instead they provision database tables with a schema to suit their needs. Once defined, they can start using the table in the Serverless database and only pay for the service based on actual usage instead of paying for the number of hours/days the database server ran, irrespective of usage.

Using FaaS, a user can run custom application code for, say, a RESTFul webservice, without provisioning any servers or container units like Dynos in case of Heroku. Like in the case of a serverless database service, the user pays for actual usage, measured in terms of number of executions and time per execution of the custom code/function deployed as a FaaS. Thus, using AWS Lambda for the Erg-Image-Service meant our AWS bill was zero to start with. When the usage grows, it is still likely to be very inexpensive given first 1 million request in a month are free per AWS account.

Implicit High Availability and Transparent Scaling

The higher level of abstraction provided by Serverless services means the service user doesn’t have to think about scaling and availability in the same was as they would when using a PaaS. When using a PaaS database, while a lot of heavy lifting around scaling and availability of the database is managed by the service provider, the user still has to think about and define scaling and availability characteristics. For example, when using AWS RDS, the user is aware of and defines availability characteristics in terms of how many Availability Zones (AZ) the RDS server should be provisioned across. Once defined, the PaaS manages the actual execution and operations to meet the defined availability needs.

On the other hand, when using a Serverless database, the service user specifies their needs in terms of the type of data they would store, number of read/write transactions they intend to run and the cloud service provider manages availability and scaling under the hood.

Likewise, FaaS services have high availability out-of-the-box and scale transparently to meet the service user’s need, without the user even having to think about these concepts. When using PaaS such as Heroku, a user is responsible for selecting a minimum number and size of Dyno to use and define how the service provider should scale the number of Dynos up or down in response to incoming traffic/load. Again, while the heavy lifting is done by the PaaS, the user still has to think about these infrastructure characteristics and define them appropriately to ensure their service scales as expected. When using FaaS on the other hand, scaling and availability is handled by the service provider and the service user doesn’t even have to define the scaling or availability characteristic.

Closing Remarks

While we have highlighted some constraints when using Serverless over PaaS, the benefits in terms of cost, transparent scaling and high availability makes Serverless an attractive choice over PaaS whenever the use-case allows.

In our context, while we used Serverless only for Erg-Image-Service, it would be beneficial to also use it for Erg-Data-Service instead of deploying it to Heroku. Beyond Java based web services, it would also be beneficial to use Serverless platform for the UI application and host the UI application on AWS S3. Both Paas and Serverless cloud services played an instrumental role in us being able to achieve our non functional requirements of scalability and high availability without having to worry about infrastructure management and operations. All this, whilst keeping infrastructure costs down, especially with the “pay for what you use” model with Serverless services.

Top comments (0)