Written by Ovie Okeh✏️

If you’re a React developer, by now you’ve most likely heard of Concurrent Mode. If you’re still wondering what that is, you’re in the right place.

The React docs do a really good job of explaining it, but I’ll summarize it here. It is simply a set of features that help React apps to stay responsive regardless of a user’s device capabilities or network speed.

Among these features is Suspense for data fetching. Suspense is a component that lets your components wait for something to load before rendering, and it does this in a simple and predictable manner. This includes images, scripts, or any asynchronous operation like network requests.

In this article, we’ll look at how Suspense for data fetching works by creating a simple app that fetches data from an API and renders it to the DOM.

Note: At the time this article was written, Suspense for data fetching was still experimental, and by the time it becomes stable, the API might have changed significantly.

What is Suspense?

Suspense is a component that wraps your own custom components. It lets your components communicate to React that they’re waiting for some data to load before the component is rendered.

It is important to note that Suspense is not a data fetching library like react-async, nor is it a way to manage state like Redux. It simply prevents your components from rendering to the DOM until some asynchronous operation (i.e., a network request) is completed. This will make more sense as we deconstruct the following code.

<Suspense fallback={<p>loading...</p>}>

<Todos />

</Suspense>

The Todos component is wrapped with a Suspense component that has a fallback prop.

What this means is that if Todos is waiting for some asynchronous operation, such as getting the lists of todos from an API, React will render <p>loading…</p> to the DOM instead. When the operation ends, the Todos component is then rendered.

But can’t we achieve the same thing with the following code?

...

if (loading) {

return <p>loading...</p>

}

return <Todos />

...

Well, kind of — but not really. In the latter snippet, we’re assuming that the async operation was triggered by a parent component and that <Todos /> is being rendered by this parent component after the operation is done.

But what if Todos was the one who triggered the operation? We would have to move that loading check from the parent component to the Todos component. What if there are more components apart from Todos, each triggering their own async requests?

This would mean that each child component would have to manage their own loading states independently, and that would make it tricky to orchestrate your data loading operations in a nice way that doesn’t lead to a janky UX.

Take a look at the example below:

<Suspense fallback={<p>loading...</p>}>

<Todos />

<Tasks />

</Suspense

Now we’ve added another Tasks component to the mix, and let’s assume that, just like the Todos component, it is also triggering its own async operation. By wrapping both components with Suspense, you’re effectively telling React not to render either one until both operations are resolved.

Doing the same thing without Suspense would most likely require you to move the async calls to the parent component and add an if check for the loading flag before rendering the components.

You could argue that that is a minor functionality, but that’s not all Suspense does. It also allows you to implement a “Render-as-You-Fetch” functionality. Let’s break this down.

Data fetching approaches

If a React component needs some piece of data from an API, you usually have to make a network request somewhere to retrieve this data. This is where the data fetching approaches come in play.

Fetch-on-render

Using this approach, you make the request in the component itself after mounting. A good example would be placing the request in the componentDidMount method or, if you’re using Hooks, the useEffect Hook.

...

useEffect(() => {

fetchTodos() // only gets called after the component mounts

}, [])

...

The reason it’s called fetch-on-render is because the network request isn’t triggered until the component renders, and this can lead to a problem known as a “waterfall.” Consider the following example:

const App = () => {

const [todos, setTodos] = useState(null)

useEffect(() => {

fetchTodos().then(todos => setTodos(todos)

}, [])

if (!todos) return <p>loading todos...</p>

return (

<div>

<Todos data={todos} />

<Tasks /> // this makes its own request too

</div>

)

}

This looks awfully similar to what I would usually do when I have a component that needs data from an API, but there’s a problem with it. If <Tasks /> also needs to fetch its own data from an API, it would have to wait until fetchTodos() resolves.

If this takes 3s, then <Tasks /> would have to wait 3s before it starts fetching its own data instead of having both requests happen in parallel.

This is known as the “waterfall” approach, and in a component with a fair number of other components that each make their own async calls, this could lead to a slow and janky user experience.

Fetch-then-render

Using this approach, you make the async request before the component is rendered. Let’s go back to the previous example and see how we would fix it.

const promise = fetchData() // we start fetching here

const App = () => {

const [todos, setTodos] = useState(null)

const [tasks, setTasks] = useState(null)

useEffect(() => {

promise().then(data => {

setTodos(data.todos)

setTasks(data.tasks)

}

}, [])

if (!todos) return <p>loading todos...</p>

return (

<div>

<Todos data={todos} />

<Tasks data={tasks} />

</div>

)

}

In this case, we’ve moved the fetching logic outside of the App component so that the network request begins before the component is even mounted.

Another change we made is that <Task /> no longer triggers its own async requests and is instead getting the data it needs from the parent App component.

There’s a subtle issue here too that may not be so obvious. Let’s assume that fetchData() looks like this:

function fetchData() {

return Promise.all([fetchTodos(), fetchTasks()])

.then(([todos, tasks]) => ({todos, tasks}))

}

While both fetchTodos() and fetchTasks() are started in parallel, we would still need to wait for the slower request between the two to complete before we render any useful data.

If fetchTodos() takes 200ms to resolve and fetchTasks() takes 900ms to resolve, <Todos /> would still need to wait for an extra 700ms before it gets rendered even though its data is ready to go.

This is because Promise.all waits until all the promises are resolved before resolving. Of course we could fix this by removing Promise.all and waiting for both requests separately but this quickly becomes cumbersome as an application grows.

Render-as-you-fetch

This is arguably the most important benefit Suspense brings to React. This allows you to solve the problems we encountered with the other approaches in a trivial manner.

It lets us begin rendering our component immediately after triggering the network request. This means that, just like fetch-then-render, we kick off fetching before rendering, but we don’t have to wait for a response before we start rendering. Let’s look at some code.

const data = fetchData() // this is not a promise (we'll implement something similar)

const App = () => (

<>

<Suspense fallback={<p>loading todos...</p>}>

<Todos />

</Suspense>

<Suspense fallback={<p>loading tasks...</p>}>

<Tasks />

</Suspense>

</>

)

const Todos = () => {

const todos = data.todos.read()

// code to map and render todos

}

const Tasks = () => {

const tasks = data.tasks.read()

// code to map and render tasks

}

This code may look a bit foreign, but it’s not that complicated. Most of the work actually happens in the fetchData() function and we’ll see how to implement something similar further down. For now, though, let’s look at the rest of the code.

We trigger the network request before rendering any components on line 1. In the main App component, we wrap both Todos and Tasks components in separate Suspense components with their own fallbacks.

When App mounts for the first time, it tries to render Todos first, and this triggers the data.todos.read() line. If the data isn’t ready yet (i.e., the request hasn’t resolved), it is communicated back to the Suspense component, and that then renders <p>loading todos…</p> to the DOM. The same thing happens for Tasks.

This process keeps getting retried for both components until the data is ready, and then they get rendered to the DOM.

The nice thing about this approach is that no component has to wait for the other. As soon as any component receives its complete data, it gets rendered regardless of whether the other component’s request is resolved.

Another benefit is that our logic now looks more succinct without any if checks to see whether the required data is present.

Now let’s build a simple app to drive these concepts home and see how we can implement the fetchData() function above.

Building the app

We’ll be building a simple app that fetches some data from an API and renders it to the DOM but we’ll be making use of Suspense and the render-as-you-fetch approach. I’m assuming you are already familiar with React Hooks; otherwise, you can get a quick intro here.

All the code for this article can be found here.

Let’s get started.

Setup

Lets create all the files and folders and install the required packages. We’ll fill in the content as we go. Run the following commands to set up the project structure:

mkdir suspense-data-fetching && cd suspense-data-fetching

mkdir lib lib/api lib/components public

cd lib/ && touch index.jsx

touch api/endpoints.js api/wrapPromise.js

cd components/

touch App.jsx CompletedTodos.jsx PendingTodos.jsx

cd ../.. && touch index.html index.css

Let’s install the required dependencies:

npm install --save react@experimental react-dom@experimental react-top-loading-bar

npm install --save-dev parcel parcel-bundler

Notice that we’re installing the experimental versions of both react and react-dom. This is because Suspense for data fetching is not stable yet, so you need to manually opt in.

We’re installing parcel and parcel-bundler to help us transpile our code into something that the browser can understand. The reason I opted for Parcel instead of something like webpack is because it requires zero config and works really well.

Add the following command in your package.json scripts section:

"dev": "parcel public/index.html -p 4000"

Now that we have our project structure ready and the required dependencies installed, let’s start writing some code. To keep the tutorial succinct, I will leave out the code for the following files, which you can get from the repo:

API

Let’s start with the files in the api folder.

wrapPromise.js

This is probably the most important part of this whole tutorial because it is what communicates with Suspense, and it is what any library author writing abstractions for the Suspense API would spend most of their time on.

It is a wrapper that wraps over a Promise and provides a method that allows you to determine whether the data being returned from the Promise is ready to be read. If the Promise resolves, it returns the resolved data; if it rejects, it throws the error; and if it is still pending, it throws back the Promise.

This Promise argument is usually going to be a network request to retrieve some data from an API, but it could technically be any Promise object.

The actual implementation is left for whoever is implementing it to figure out, so you could probably find other ways to do it. I’ll be sticking with something basic that meets the following requirements:

- It takes in a Promise as an argument

- When the Promise is resolved, it returns the resolved value

- When the Promise is rejected, it throws the rejected value

- When the Promise is still pending, it throws back the Promise

- It exposes a method to read the status of the Promise

With the requirements defined, it’s time to write some code. Open the api/wrapPromise.js file and we can get started.

function wrapPromise(promise) {

let status = 'pending'

let response

const suspender = promise.then(

(res) => {

status = 'success'

response = res

},

(err) => {

status = 'error'

response = err

},

)

...to be continued...

What’s happening here?

Inside the wrapPromise function, we’re defining two variables:

-

status: Used to track the status of the promise argument -

response: Will hold the result of the Promise (whether resolved or rejected)

status is initialized to “pending” by default because that’s the default state of any new Promise.

We then initialize a new variable, suspender, and set its value to the Promise and attach a then method to it. Inside this then method, we have two callback functions: the first to handle the resolved value, and the second to handle the rejected value.

If the Promise resolves successfully, we update the status variable to be “success” and set the response variable to the resolved value.

If the Promise rejects, we update the status variable to be “error” and set the response variable to the rejected value.

...continued from above...

const read = () => {

switch (status) {

case 'pending':

throw suspender

case 'error':

throw response

default:

return response

}

}

return { read }

}

export default wrapPromise

Next, we create a new function called read, and inside this function, we have a switch statement that checks the value of the status variable.

If the status of the promise is “pending,” we throw the suspender variable we just defined. If it is “error,” we throw the response variable. And, finally, if it is anything other than the two (i.e., “success”), we return the response variable.

The reason we throw either the suspender variable or the error response variable is because we want to communicate back to Suspense that the Promise is not yet resolved. We’re doing that by simulating an error in the component (using throw), which will get intercepted by the Suspense component.

The Suspense component then looks at the thrown value to determine if it’s an actual error or if it’s a Promise.

If it is a Promise, the Suspense component will recognize that the component is still waiting for some data, and it will render the fallback. If it’s an error, it bubbles the error back up to the nearest Error Boundary until it is either caught or it crashes the application.

At the end of the wrapPromise function, we return an object containing the read function as a method, and this is what our React components will interact with to retrieve the value of the

Promise.

Lastly, we have a default export so that we can use the wrapPromise function in other files. Now let’s move on to the endpoints.js file.

endpoints.js

Inside this file, we’ll create two asynchronous functions to fetch the data that our components require. They will return a Promise wrapped with the wrapPromise function we just went through. Let’s see what I mean.

import wrapPromise from './wrapPromise'

const pendingUrl = 'http://www.mocky.io/v2/5dd7ff583100007400055ced'

const completedUrl = 'http://www.mocky.io/v2/5dd7ffde310000b67b055cef'

function fetchPendingTodos() {

const promise = fetch(pendingUrl)

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((res) => res.data)

return wrapPromise(promise)

}

function fetchCompletedTodos() {

const promise = fetch(completedUrl)

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((res) => res.data)

return wrapPromise(promise)

}

export { fetchPendingTodos, fetchCompletedTodos }

The first thing we do here is import the wrapPromise function we just created and define two variables to hold the endpoints we’ll be making our requests to.

Then we define a function, fetchPendingTodos(). Inside this function, we initialize a new variable, promise, and set its value to a Fetch request. When this request is completed, we get the data from the Response object using res.json() and then return res.data, which contains the data that we need.

Finally, we pass this promise to the wrapPromise function and return it. We do the same thing in fetchCompletedTodos(), with the only difference being the URL we’re making our request to.

At the end of this file, we export an object containing both functions to be used by our components.

API recap

Let’s go through all we have done so far.

We defined a function, wrapPromise, that takes in a Promise and, based on the status of that Promise, either throws the rejected value of the Promise, the Promise itself, or returns the resolved value of the Promise.

wrapPromise then returns an object containing a read method that allows us to query the value (or, if not resolved, the Promise itself) of the Promise.

endpoints.js, on the other hand, contains two asynchronous functions that fetch data from a server using the Fetch API, and they both return promises wrapped with the wrapPromise function.

Now on to the components!

Components

We now have the “backend” for our app ready, so it’s time to build out the components.

index.jsx

This is the entry point of our application ,and we’ll be creating it first. This is where we’ll mount our React app to the DOM.

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

import App from './components/App'

const mountNode = document.querySelector('#root')

ReactDOM.createRoot(mountNode).render(<App />)

This should look familiar if you’ve ever worked on a React app, but there are some subtle differences with the way you would usually attach your app.

We import React, ReactDOM, and our root component as usual. Then we target the element with an ID of “root” in the DOM and store it as our mountNode. This is where React will be attached.

The last part is what contains unfamiliar code. There’s a new additional step before we attach the app using ReactDOM. Usually, you’d write something like this:

ReactDOM.render(<App />, mountNode)

But in this case, we’re using ReactDOM.createRoot because we’re manually opting in to Concurrent Mode. This will allow us to use the new Concurrent Mode features in our application.

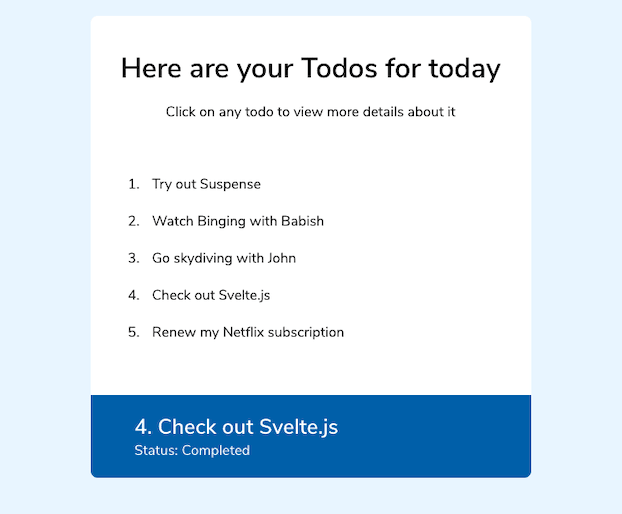

App.jsx

This is where most of the magic happens, so we’ll go through it step by step.

import React, { Suspense } from 'react'

import { PendingTodos, CompletedTodos } from '.'

const App = () => {

return (

<div className="app">

<h1>Here are your Todos for today</h1>

<p>Click on any todo to view more details about it</p>

<h3>Pending Todos</h3>

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Pending Todos...</h1>}>

<PendingTodos />

</Suspense>

<h3>Completed Todos</h3>

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Completed Todos...</h1>}>

<CompletedTodos />

</Suspense>

</div>

)

}

export default App

Right at the beginning, we have our React import, but notice that we also bring in Suspense, which, if you remember, lets our components wait for something before rendering. We also import two custom components, which will render our todo items.

After the imports, we create a new component called App, which will act as the parent for the other components.

Next, we have the return statement to render our JSX, and this is where we make use of the Suspense component.

The first Suspense component has a fallback of <h1>Loading Pending Todos…</h1> and is used to wrap the <PendingTodos /> component. This will cause React to render <h1>Loading Pending Todos…</h1> while the pending todos data is not ready.

The same things applies to the <CompletedTodos /> component, with the only difference being the fallback message.

Notice that the two Suspense components are side by side. This simply means that both requests to fetch the pending and completed todos will be kicked off in parallel and neither will have to wait for the other.

Imagine if CompletedTodos gets its data first, and you begin to go through the list only for PendingTodos to resolve a little while later. The new content being rendered will push the existing completed todos down in a janky way, and this could disorient your users.

If, however, you want the CompletedTodos component to render only when the PendingTodos component has finished rendering, then you could nest the Suspense component wrapping CompletedTodos like so:

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Pending Todos...</h1>}>

<PendingTodos />

<h3>Completed Todos</h3>

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Completed Todos...</h1>}>

<CompletedTodos />

</Suspense>

</Suspense>

Another approach is to wrap both Suspense components in a SuspenseList and specify a “reveal order,” like so:

<SuspenseList revealOrder="forwards">

<h3>Pending Todos</h3>

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Pending Todos...</h1>}>

<PendingTodos />

</Suspense>

<h3>Completed Todos</h3>

<Suspense fallback={<h1>Loading Completed Todos...</h1>}>

<CompletedTodos />

</Suspense>

</SuspenseList>

This would cause React to render the components in the order they appear in your code, regardless of which one gets its data first. You can begin to see how ridiculously easy it becomes to organize your application’s loading states as opposed to having to manage isLoading variables yourself.

Let’s move on to the other components.

CompletedTodos.jsx

import React from 'react'

import { fetchCompletedTodos } from '../api/endpoints'

const resource = fetchCompletedTodos()

const CompletedTodos = () => {

const todos = resource.read()

return (

<ul className="todos completed">

{todos.map((todo) => (

<li key={todo.id}>{todo.title}</li>

))}

</ul>

)

}

export default CompletedTodos

This is the component that renders the list of completed todo items, and we start off by importing React and the fetchCompletedTodos function at the top of the file.

We then kick off our network request to fetch the list of completed todos by calling fetchCompletedTodos() and storing the result in a variable called resource. This resource variable is an object with a reference to the request Promise, which we can query by calling a .read() method.

If the request isn’t resolved yet, calling resource.read() will throw an exception back to the Suspense component. If it is, however, it will return the resolved data from the Promise, which, in this case, would be an array of todo items.

We then go ahead to map over this array and render each todo item to the DOM. At the end of the file, we have a default export so that we can import this component in other files.

PendingTodos.jsx

import React from 'react'

import { fetchPendingTodos } from '../api/endpoints'

const resource = fetchPendingTodos()

const PendingTodos = () => {

const todos = resource.read()

return (

<ol className="todos pending">

{todos.map((todo) => (

<li key={todo.id}>{todo.title}</li>

))}

</ol>

)

}

export default PendingTodos

The code for the PendingTodos component is identical to the CompletedTodos component, so there’s no need to go through it.

Components recap

We’re done with coding our components, and it’s time to review what we’ve done so far.

- We opted in to Concurrent Mode in our

index.jsxfile - We created an

Appcomponent that had two children components, each wrapped in aSuspensecomponent - In each of the children components, we kicked off our network request before they mounted

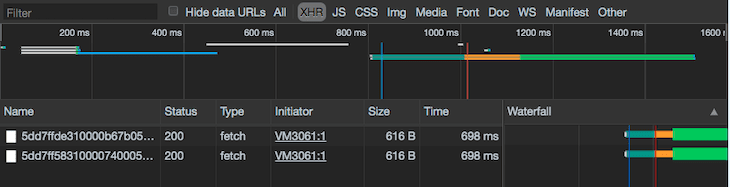

Let’s run our app and see if it works. In your terminal, run npm run dev and navigate to http://localhost:4000 in your browser. Open the Networks tab in your Chrome developer tools and refresh the page.

You should see that the requests for both the completed and pending todo items are both happening in parallel like so.

We have successfully implemented a naive version of Suspense for data fetching, and you can see how it helps you orchestrate your app’s data fetching operations in a simple and predictable manner.

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve taken a look at what Suspense is, the various data fetching approaches, and we’ve gone ahead and built a simple app that makes use of Suspense for data fetching.

While Concurrent Mode is still experimental, I hope this article has been able to highlight some of the nice benefits it will bring by the time it becomes stable. If you’re interested in learning more about it, I’d recommend you read the docs and try to build a more complex app using it.

Again, you can find all the code written in this tutorial here. Goodbye and happy coding. ❤

Editor's note: Seeing something wrong with this post? You can find the correct version here.

Plug: LogRocket, a DVR for web apps

LogRocket is a frontend logging tool that lets you replay problems as if they happened in your own browser. Instead of guessing why errors happen, or asking users for screenshots and log dumps, LogRocket lets you replay the session to quickly understand what went wrong. It works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

In addition to logging Redux actions and state, LogRocket records console logs, JavaScript errors, stacktraces, network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. It also instruments the DOM to record the HTML and CSS on the page, recreating pixel-perfect videos of even the most complex single-page apps.

Try it for free.

The post Experimental React: Using Suspense for data fetching appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

Top comments (0)