For the longest time after React was released I had difficulty really understanding how it was supposed to be used. Coming from years of MVC/MVVM experience in Java, C#/WPF, and Angular, React seemed strange. The basic tutorials and examples showed 'how' you do something, but never why, and there was pretty much no separation between view and controller logic.

Eventually I sat down and wrote something using React and Redux, following the 'best practices', so I could understand the decisions that went into the frameworks and how they could be used.

Components

So what did I learn?

First, React is a different way of thinking of applications, but also, it's almost entirely concerned with view and view state. MVC generally separates the view state from the view and keeps it in the controller along with other application state information and in MVVM, the entire purpose of the 'VM' ViewModel is to keep track of view state. But in React, these two are combined into one abstraction called a "Component".

Components are relatively simple. They contain the logic for rendering your view to the page given a view state, and optional methods for changing that state.

A simple 'stateless' component is just the render logic. These can be represented by just a function that take a "props" object.

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

Note: I'm using JSX in these examples. It's a layer on top of your javascript that lets you write HTML-like code elements that are compiled into regular javascript. I recommend reading the JSX intro for more information. (It also wreaks havoc on my current code highlighter.)

Components can contain other components, creating a component 'tree'. In this way, it's just like HTML, where an HTML element can contain other elements.

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

function TimeDisplay(props) {

return <h2>It is {props.time}.</h2>;

}

function Greeter() {

return (

<div>

<Welcome name="World">

<TimeDisplay time={new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}/>

</div>

);

}

Stateful components that have states that can change are generally more complicated and derived from a 'Component' base class. State updates are triggered by external events (usually UI) by using the setState() function.

This example will update on every interval "tick" creating a clock.

Note: This example is pulled almost entirely from the React documentation on State and Lifecycle.

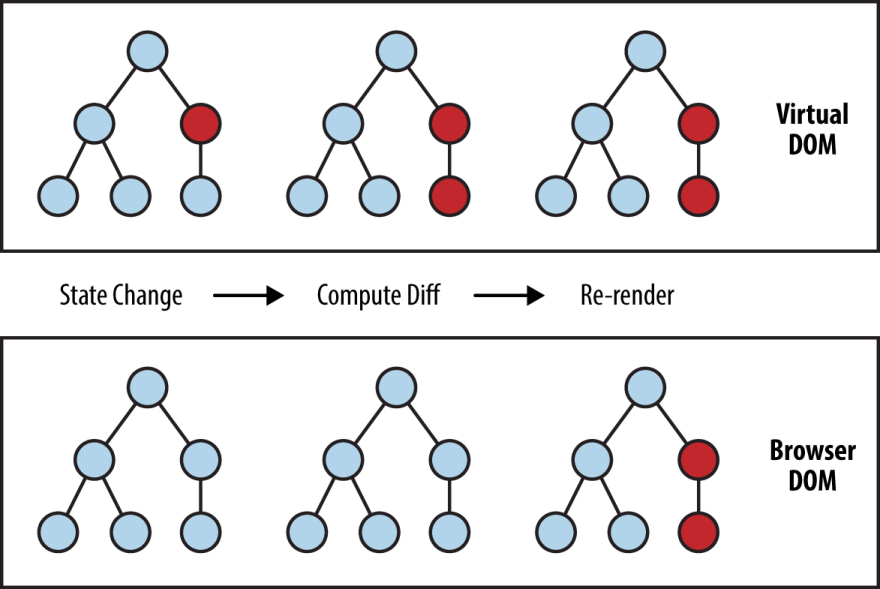

Updates, rendering, and the Virtual Dom

When a component updates its state, it causes a re-render. The current component and its children will update.

Instead of directly updating the DOM, components update the "Virtual DOM", which is a DOM tree in memory. It's not rendered directly to the browser. This virtual DOM is then compared against the 'real' DOM and the real DOM is updated with just the changes between the two.

Combined with the 'reactive' component updates (the component only updates in reaction to setState()), this makes React quite good at only updating what's necessary and minimizing the visible page updates (generally the most computationally expensive part of a change.)

The trade-off for this performance is higher memory use: The application's component tree is in memory twice. Because this is all abstracted away from the application developer, though, it allows the framework to optimize performance and is generally not something you need to think about.

What about the rest of the app?

React's simple pattern is quite flexible, allowing for state, view, and events, but it's also quite limiting. The component tree pattern requires your dependencies to be passed through the entire tree to get to child components.

This can get especially awkward if you introduce a new UI component that needs to reference a piece of application state logic that's not used in that area of the UI. You have to either add it to the all the parent components or alternatively use some kind of js 'global'. Neither is a good solution. Your application state rarely mirrors the UI.

Redux for application state

The solution to this problem is to move the application state into a separate store. The most popular is Redux, though there are plenty of other options.

Redux provides three main things:

- An application level state store.

- A way of updating that store from anywhere in the UI.

- A way of updating the view state of components when the store is updated.

Redux is unidirectional, meaning events always go through it in one way.

React component (events) => Dispatch (actions) => Store update (reducer) => Component update (connect)

Let's go through this flow in order.

An event can be generated from anywhere, but is generally a UI event like a mouse click.

Note: Handling events in React has a bunch of caveats. As always, checkout the docs for more information.

class SpaceShip extends React.Component {

moreSpeedClick = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

console.log('zoom');

};

lessSpeedClick = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

console.log('mooz');

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<div>{this.props.currentSpeed}</div>

<button onClick={this.moreSpeedClick}>More Speed</button>

<button onClick={this.lessSpeedClick}>Less Speed</button>

</div>

);

}

}

This event creates a Redux Action. Actions are simple objects that describe what update needs to happen in the store.

// make it go faster by an increment of 1

{ type: "faster", increment: 1}

Redux recommends creating "Action Creators", which are just functions that create these objects. Right now our actions are very simple, but in a larger app they might have lots of properties or even logic, so a function helps keep things clean.

function faster(increment) {

return { type: 'faster', increment: increment };

}

function slower(decrement) {

return { type: 'slower', decrement: decrement };

}

These actions are 'dispatched' through the dispatcher. The dispatcher is passed to the component in its properties and passes action objects to redux.

class SpaceShip extends React.Component {

moreSpeedClick = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

this.props.dispatch(faster(1));

};

lessSpeedClick = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

this.props.dispatch(slower(1));

};

render() {

return (

<div>

<div>{this.props.currentSpeed}</div>

<button onClick={this.moreSpeedClick}>More Speed</button>

<button onClick={this.lessSpeedClick}>Less Speed</button>

</div>

);

}

}

The 'store' itself is a plain javascript object. Unlike Angular, the store object isn't directly manipulated or observed by Redux and can be arranged in anyway that makes sense to the application.

When an action is dispatched to the store, they're passed through functions called 'reducers' which take the previous state and an action, and then returns an updated state object. The common pattern is to use a switch statement on the 'type' of the action objects. Because this is just a function and plain javascript objects, however, you can do whatever you want.

function spaceshipReducer(state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'FASTER':

return { speed: state.speed + action.increment };

case 'SLOWER':

return { speed: state.speed - action.decrement };

default:

return state;

}

}

const initState = { speed: 0 };

const store = createStore(spaceshipReducer, initState);

One of the requirements of Redux applications is that your store be "immutable". This means that instead of updating existing objects, you entirely replace them. This allows you to do simple reference comparisons that can greatly impact the performance of larger applications. The downside is it can make your reducers considerably more difficult to read.

// this does the same thing as the 'faster' case above

// You would use this pattern for more complex state trees

return Object.assign({}, state, {

speed: state.speed + action.increment,

});

Note: Read more in about immutable changes in the redux basics tutorials. If using newer javascript features, there are a few other options as well.

After any action is received by the store, it fires an update event. React components are wrapped in a container component that triggers updates when the store updates. A component is wrapped using the redux 'connect' function that maps the application store to the component properties. If you use best practices (immutable), this map is bright enough to tell when that section of the state is different or not. Other than that, the wrapper component doesn't do much magic. It simply subscribes to the store 'update' event and uses setState() when something changes to trigger the normal react update.

It's also common to map the dispatch actions to properties rather than passing the entire dispatch function in.

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

function mapStateToProps(state) {

return {

currentSpeed: state.speed,

};

}

function mapDispatchToProps(dispatch) {

return {

faster: (increment) => dispatch(faster(increment)),

slower: (decrement) => dispatch(slower(decrement)),

};

}

const SpaceShipContainer = connect(

mapStateToProps,

mapDispatchToProps

)(SpaceShip);

And here's all of it together.

Note: You'll see a "Provider" component in the full example. The Provider simply makes the redux store available to any connected "container" component without the developer having to do anything. It does this by utilizing some low-level React features that you generally don't need to worry about.

Redux Middleware and async actions

This covers the basic cases of reacting to UI events, but doesn't help with working with web services and AJAX callbacks. In the Angular world, these functions are usually placed into services that are injected into your controllers. In general, Redux doesn't provide a solution for this, but what it does provide is a centralized way of passing messages around.

With Redux, the only things that are injected to a component is the state and dispatcher. The state is just a plain object, but the Redux provides a way of extending the capabilities of the dispatcher through the use of "Middleware".

Middleware is a function that is called before the action is passed on to the reducer. One of the simplest and most commonly used middlewares is redux-thunk, which allows you to dispatch async actions. Instead of passing an action object, you pass in a function to the dispatcher. Redux-thunk sees the function and calls it, passing in the dispatcher and state.

When I say simple, I mean it. Here's the important part of redux-thunk:

if (typeof action === 'function') {

return action(dispatch, getState, extraArgument);

}

return next(action);

If the action is a function, it calls it, passing in the dispatcher, getState accessor, and an optional argument. If the action is not a function, it's just passed on to the default behavior.

Note: getState() returns the current state at the time of calling. This has two purposes: You can get the state before and after 'dispatch' has been called (letting you perform complex logic in your action creators), and you can get the state after an async action completes (important since the state could have changed since the action began.)

Here's an example of what a 'thunk' looks like. Compare this action creator to the 'faster' and 'slower' examples above.

function warpSpeed(warp) {

return function(dispatch) {

// we're using setTimeout for our async action

// but this could be an http call, or whatever

setTimeout(() => {

// dispatch the state update action

// this could also be another thunk!

dispatch(faster(warp));

}, 1000);

};

}

// warpSpeed returns a function that is called by the middleware,

// but the function signature is the same as before.

dispatch(warpSpeed(10));

This simple pattern acts a lot like dependency injection at the function level, or a command/mediator pattern. If you need additional 'services' or configuration you can inject them through the "extra Parameter" option.

function warpSpeed(warp) {

return function(dispatch, getState, extraArgument) {

setTimeout(() => {

dispatch(faster(warp));

}, extraArgument.warmupTime);

};

}

I have somewhat mixed feelings on this pattern since it's mixing your store updates and mediated command messages, but passing everything through the dispatcher does keep things simple, so I don't consider it a big deal.

Other thoughts

Redux is worthy of an entire article. It’s both opinionated, but flexible. I recommend reading through their entire documentation to really get a handle on how it can be used. Also, by learning Redux you'll have a lot of the basic React concepts reinforced.

There are also plenty of alternatives. Checkout MobX for something more similar to Angular (more magic), or even roll your own (no magic)!

Since I wrote this article, I created my own alternative to redux called Honk. It was created for simple projects with typescript in mind. Check it out!

It should also be mentioned that Angular and Vue are both component heavy now, having taken a lot of cues from React. Learning one will likely help you with the others.

Finally, I want to mention that react + redux using best practices is verbose. There's very little 'magic' that hides code from the developer, and combined with redux's "best practices" you end up with lots of extra infrastructure code. The up sides are better understandability - you'll often hear people say react and redux is easier to 'reason' about - and better code separation, especially for larger projects and teams.

Good luck, and happy coding!

Top comments (0)