Introduction

In the beginning of 2021, I dove into the world of software engineering and technology in general. I learned amazing tools and languages like Linux and its distributions; the Visual Studio Code; the triad of web development with HTML, CSS and JavaScript; React for creating user interfaces and much more. However, the one thing that caught my attention the most was Git. Not only for its prevalence in the market, but for its elegance and efficiency. In this article I intend to present the basics of how Git works, as well as show why it is so powerful. I do not intend to make a tutorial, but rather a theoretical explanation of the main concepts. The example images in this article are in portuguese, the original language this text was written in.

Git came to solve the file version control problem. You can relate to this problem if you ever had a folder on your computer with file names like work.pdf, work1.pdf, work2.pdf, work-final.pdf, work-really-final.pdf? When we are working individually with a single document this may seem harmless, but in a project with dozens of files and many people working simultaneously, it can become a nightmare.

Before explaining how Git and GitHub work, and why they make life so much easier, it’s important to check some definitions. Git is the version control software used in most development projects today. It keeps track of all changes made to a file since its creation, allowing the user to “go back in time” to each of those changes if they want to. Git is a free, open-source program, initially developed by Linus Torvalds, who also started the development of the Linux kernel. It is mostly used as a CLI(Command Line Interface) program, or as a desktop application with a GUI(Graphic User Interface).

GitHub is a website that runs Git under the hood, and offers a user-friendly interface for versioning our files. GitHub allows your projects to be public, so anyone on the internet can view it, suggest changes, and make comments. Later in this article, I’ll explain how the interaction between Git, used on a local machine, and GitHub on the web happens.

How Git Works (in a nutshell)

The moment we create a git repository, we have a folder in our computer that will keep track of everything that happens there, both adding and removing content. Inside the repository a hidden .git folder is created, which is where the internal working mechanics takes place. For those interested, the official Git documentation is quite complete and has an entire book explaining in detail how it works.

Git usage can be represented by four main concepts (or commands): commit, branch, pull request and merge. And three others related to the interaction between Git and GitHub: clone, pull and push.

Commit is the packaging of a change to the file. Each change made and confirmed generates a commit, which is a snapshot of the difference between the file’s previous state and its current state.

In this case, we have a test.txt file, which initially had 3 lines. A new commit has been made and 2 new lines were included. This image was taken from GitHub, where I created a repository that contains only the test.txtfile.

Git keeps track of all commits, in a chronologically ordered sequence. It is possible to check all the commits of a file since its creation, and if necessary restore the file to its state in a given point in the past. Each node in the image below represents a commit in the file's history. In this case, 3 were performed in total.

You might be wondering about the meaning of the word main in the image, and that brings us to Git's second fundamental concept: branches. Each sequence of commits is present in a branch, and by default the repository starts with a primary branch called main. It allows us to create new branches for the change history of a file, in case it is necessary to make edits without impacting the main branch. This is very useful when testing something new that we don't know if it will stick around.

An interesting fact is that not long ago the main branch was called master. Git changed the name because the word master has ties to slavery times, when people called slave owners their masters. Way to go, Git and Github!

In this example, a new branch called new-branch was created and 3 new commits were made to it. Commits made in main remain there, untouched, while commits from the new one are included in the new one. In it we have all the commits made in main plus those made exclusively in new-branch.

Commits in main and new-branch. Note that the first 3 commits from the new branch are the same as those from the main. The 6-digit identifier on the right is called a hash. Which is a unique identifier for each commit.

The concept of branching can be a little hard to grasp at first. I recommend that you look up for a tutorial or read the official documentation, if it’s not clear.

Branching opens many doors. We can test whatever we want without harming our work on the main branch. However, the point of having branches is to eventually merge them. How do we do it when one of these branches turns out great, and we want it to become our main work?

The pull request is a request from the new branch for the main one to pull its work. In other words, the main branch can incorporate the work done in the newer one. In this case, we'll open a pull request to ask main to merge the work done in new-branch.

Pull Request: at the top we can read that my user wants to merge into main 3 of the additional commits coming from the new-branch.

There is a discussion among users that the pull request name is not the most intuitive. After all, we are asking for a merge to be performed, correct? Some say that the most intuitive name would be merge request. And other platforms similar to GitHub actually use this name.

Finally, we accept the pull request and merge the new branch with the main one. Our main now incorporates all the content we created in new-branch, in addition to the content it already had.

Now, new-branch can be deleted, as its content is already embedded in the main branch.

How Git and GitHub work together

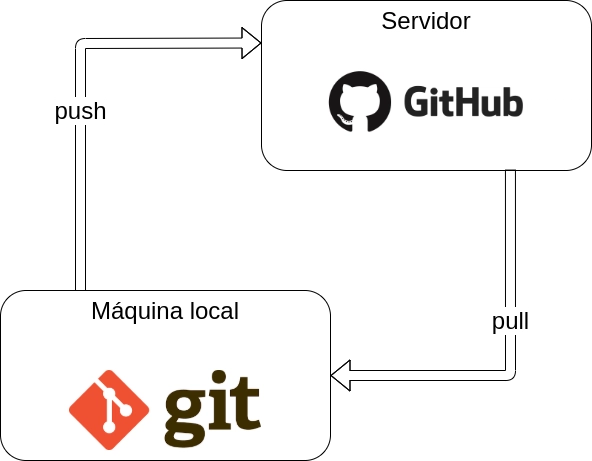

This entire process of creating files, branches and merges can be done either on your local machine, using the Git software, or directly on the GitHub website. But the great power of these tools lies in their use together. The same git repository can have a local copy, on your computer, and a remote copy, which is stored on a GitHub server in the cloud, associated with your user account on the website.

When you clone a remote GitHub repository on your local machine, you have a copy of these files, and on it you can do whatever you want: commits, new branches and merges. After working locally, it is common to upload this work to GitHub so that it is available on the internet. That's where the push comes in.

In the diagram, you can also see the pull, which is exactly the reverse path: bringing changes from the remote repository to your local machine. This operation is very useful when there are teams with many people working on the same project, each on their own machine, but using the same shared remote repository. In this scenario, which is the standard in teams using GitHub, each person can make a new branch, copy it to their local machine, do the necessary work, push it to the server, and then open a pull request to have their work merged.

Collaboration and organization

Version control functionality is interesting and becomes an extremely powerful tool when used on a large scale. Most of today's most important open-source projects, such as the Linux kernel, Visual Studio Code, React and many others, are made in this distributed model, where developers from anywhere in the world have access to the source code, they can work locally on the project, propose changes and improvements, and all without compromising the integrity of the original project or the work of others.

The open-source world is fascinating and deserves an entire article just about it. The Ingenuity robot, which recently took flight in the atmosphere of Mars, internally runs software that relies on open-source libraries. Those have contributions from approximately 12,000 developers on GitHub worldwide.

An important point to make is that Git and GitHub are not just tools for programmers, they can be used with any kind of file. Certainly, the prevalence in the technology market is much greater, since it's not intuitive for non-programmers and has a considerable learning curve. But they are definitely worth it to keep the work structure more organized, collaborative and dynamic.

To clarify this last point, I recommend watching the YouTube channel The Coding Train, by Professor Daniel Shiffman from New York University, called Git and GitHub for Poets. In the videos, Professor Shiffman, who has an incredibly engaging way of explaining things, shows how to use Git and GitHub to work on a text file of a poem, without writing a single line of code. I strongly recommend checking it out.

Top comments (1)

Add the "todayilearnt" tag!