The C# nullability features introduced in C#8 help you minimize the likelihood of encountering that dreaded System.NullReferenceException. Nullability syntax and annotations give hints on whether a type can be nullable or not. Better static analysis is available to catch unhandled nulls while developing your code. What’s not to like?

Introducing explicit nullability into an existing code bases is quite an effort. There’s much more to it than just sprinkling some ? and ! throughout your code. It’s not a silver bullet either: you’ll still need to check non-nullable variables for null.

Throughout a series of blog posts, we’ll learn more about C# nullability, and cover some techniques and approaches that worked for me when migrating an existing codebase to using nullable reference types.

Let’s start at the beginning.

Reference types, value types, and null

You may have heard of null being the “billion-dollar mistake”. In 2009, Tony Hoare, the creator of the ALGOL W programming language, apologized for his billion-dollar mistake: null references. His original goal was to ensure that using any reference would be absolutely safe, validated with compiler checks. But supporting a null reference was easy to do, so he did - leading to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes in many systems out there. Other languages copied this idea, resulting in null references probably causing a billion dollars of pain and damage ever since.

Nullable reference types have always been part of C#: a reference type can be either a reference, or null. Consider the following example:

string s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine($"Length of '{s}': {s.Length}");

When s is not null, a message will be written to the console. But what happens when s is null? Exactly: a NullReferenceException is thrown when accessing the Length property of… null.

We can add a check for null before accessing this property:

string s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine(s != null

? $"Length of '{s}': {s.Length}"

: "String is null.");

How do you know whether you need that check? If GetValue() never returns null, how would you know if you need to check s when accessing its properties?

For value types, such as int, bool, decimal, structs like DateTime or custom implementations, etc., you can make use of Nullable<T> to make those value types “nullable”, and have a safe way of accessing them.

Note: value types can’t really be null - they are values, not references. With

Nullable<T>, you’re wrapping the value to be able to keep track of this additionalnullstate.

There is some compiler magic that converts int? into Nullable<int>. When accessing a nullable value type, you know it will either be null or contain a value, and that a check has to be made. With a nullable DateTime, we could write the above example as follows:

DateTime? s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine(s.HasValue

? $"The date is: {s.Value:O}"

: "No date was given.");

The key difference here is intent. With our string before, you have no idea if null is to be expected. It can never happen, it may happen - you only know by looking into the GetValue() function (or take the safe approach and always add null checks). With value types, the intent is more clear. A DateTime can never be null, whereas a Nullable<DateTime> tells you that a check for null (or .HasValue) is required.

What are nullable reference types?

With C#8, nullable reference types (NRT) were introduced and help convey the intent that a reference can be null or will never be null.

Let’s start by pointing out that reference types have always been nullable, as we saw in the introduction. They have been since the first version of C# - string s = null is perfectly fine, and every reference type really always has been a nullable reference type.

Why am I pointing this out? Reference types have been nullable forever, and now we’re flipping that idea by thinking of them as non-nullable by default, and adding syntax to annotate them as being nullable. The annotations help while writing and compiling your code, but don’t provide a runtime safety net. Let’s have a look at what that means.

With nullable reference types enabled, the earlier example tells the compiler that we expect s to not be null (otherwise we’d declare string? s), and we can safely remove the null check…

string s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine($"Length of '{s}': {s.Length}");

string? GetValue() => null;

…or can we? Surprisingly, you can compile and run the above code, even with GetValue() returning a string that is null. You’ll just see a NullReferenceException is thrown when accessing the Length property of… null.

So what are C#8 nullable reference types? I like to call them nullable annotations - NRT’s annotate your code with what their nullability can be.

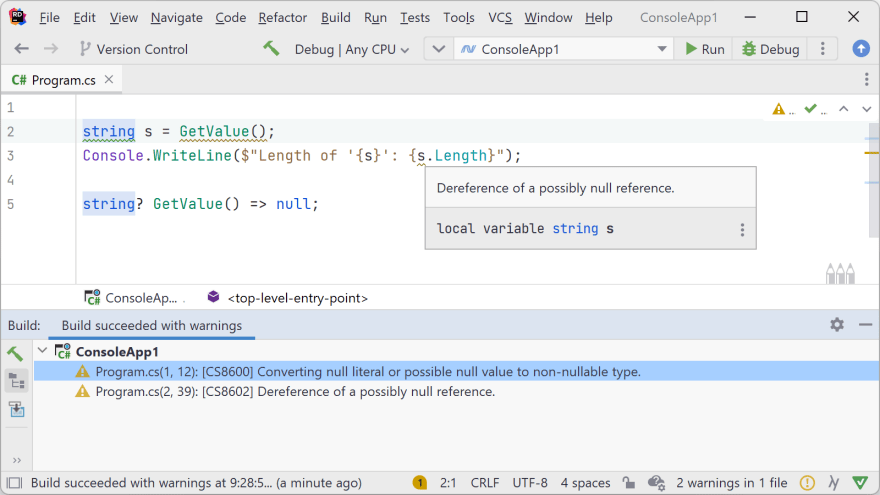

When you compile the above code, or look at it in an IDE, you’ll see several warnings that mention you are doing something that may haunt you when you run the application:

- CS8600 - Converting null literal or possible null value to non-nullable type.

- CS8602 - Dereference of a possibly null reference.

Thanks, IDE! Thanks, C# compiler! While this may all blow up at runtime, at least I get enough warnings to go fix this code. And that fixing can be done almost automatically, with a quick-fix.

After applying these fixes, we’re essentially back at our initial example, but this time annotated with what we expect. Again, the IDE and compiler will help us out, and if we change that GetValue() function to return a non-nullable string, the tooling will tell us we’re doing redundant null checks, and offer to remove them.

string? s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine($"Length of '{s}': {s.Length}");

string GetValue() => "";

Flow analysis

There are some interesting things when it comes to nullability and flow analysis.

For example, var is always considered nullable. The C# language team decided to always treat var as nullable, and to rely on flow analysis to determine when the IDE or compiler should warn.

In our example, the nullability of s is determined by the annotations of the GetValue() function.

var s = GetValue();

Console.WriteLine($"Length of '{s}': {s.Length}");

string GetValue() => "";

Many IDEs will render inlay type hints to help you determine what a var could be, based on flow analysis. Here’s a quick example. Note the inlay hint on var s change when nullability of the GetValue() function changes. Also note the squiggly at s.Length, where flow analysis determines whether dereferencing Length is potentially going to get you into trouble.

Cool, eh? Things become even cooler when you do null checks. Here are two methods:

void MethodA(string? value) {

Console.WriteLine(value.Length); // CS8602 - Dereference of a possibly null reference.

}

void MethodB(string? value) {

if (value == null) return;

Console.WriteLine(value.Length); // No warning, null check happened before

}

In MethodA(), we’re not doing a null check for the value parameter, and flow analysis will warn about dereferencing a possibly null reference. In MethodB(), flow analysis determined we are doing a null check, and is fine with accessing .Length since there’s no chance of this line of code being hit with a null reference.

The null-forgiving operator

Before wrapping up, there’s one more topic I want to get into. The null-forgiving operator (also known as the null-suppression operator, or the dammit-operator), !.

When using nullable reference types, an expression can be postfixed with ! to tell the IDE and compiler’s static flow analysis to “ignore” the null state of the expression.

Here are two examples, where ! is telling the flow analysis that a nullable state can be ignored:

string? a = null;

Console.WriteLine(a!.Length);

string? b = null!;

Console.WriteLine(b.Length);

Of course, this is not ideal - both of the above examples will throw NullReferenceException when running the app.

There are valid use cases, though. Flow analysis may not able to detect that a nullable value is actually non-nullable. You can suppress those cases, if you know a reference is not going to be null. In the following example, IsValidUser() checks for null, so we can suppress the null warning we’d get otherwise in the Console.WriteLine call:

var user = _userManager.GetUserById(id);

if (IsValidUser(user)) {

Console.WriteLine($"Username: {user!.Username}");

}

public static bool IsValidUser(User? user)

=> !string.IsNullOrEmpty(user?.Username);

Note: there are better ways to solve some of these suppressions, using special attributes. I’ll cover these in the next post.

Another case is when migrating a code base that does not yet use nullable reference types. You may want to (temporarily) suppress warnings on a certain code path, and not yet care about nullability while you are working on another part of the code base.

Yet another case could be with unit tests. Maybe you do want to check what happens if someone passes null into a function that expects a non-null reference. In those situations, you could pass null! and see what happens.

Do keep in mind the null-forgiving operator effectively disables flow analysis, and could easily hide nullability bugs in your code base. Use it with care, and consider the use of the null-suppressing operator a code smell.

Conclusion

With nullable reference types enabled, you get improved static flow analysis on your code that helps determine if a variable may be null before dereferencing it. Variable annotations can be used to explicitly declare the intended null-state for that variable - adding ? to convey a null reference is possible.

Nullable reference types don’t give you runtime safety when it comes to nullability, but design-time and compile-time help is great to have!

In the next post, we’ll look at some internals and the nullable annotation context.

Top comments (0)