Spaghetti code, architecture that isn't well-thought-out, growth and supportability challenges - being a software engineer, you get plenty of opportunities to experience these and similar effects throughout your career. As much as we love to criticize others for choices they made (and that we have to live with), let's be serious for a moment: Very few engineers are actually making a conscious choice to write a bad code.

"I have an idea! Lets write a fundamentally bad code and make the life of everyone who ends up using it and maintaining it really miserable!"

This is not how it works. Behind every "bad" software module that someone has to maintain or use, there is always someone who either really didn't know any better or thought that implementing it the way they chose seemed to be a good idea at the time.

As the field of software engineering evolves and becomes more modern, knowledge gaps reduce, and, while not everyone has to be the mean lean coding machine, there is a lot of available knowledge and support that would explain proper ways to implement certain software solutions. Even if you are inexperienced in what you're doing - "not knowing any better" becomes harder and harder in our always connected, Google this/Google that world.

So, in a nutshell, it all boils down to choosing the right strategy of managing investments (and, therefore, progress) in the proper infrastructure / architecture vs implementing new product functionality. Choosing the right strategy is akin to implementing a design pattern. Upon reaching this conclusion, one can start considering various strategies based on the needs and the constraints of the business requirements. Below we are listing a number of prominent strategies, talking about the pros and the cons of each.

1⃣ Build Product, Deal with Infrastructure / Architecture Later

This approach is rumored to have originated in the start-up world. Some people will blame The Lean Startup principles for promoting the idea (not necessarily accurate), while others will cite the general challenge younger generations have with Delayed Gratification. In real life, one can find many cases of this approach taking place in established enterprises, that are interested in innovating, while being reluctant to make significant investments prior to seeing any "justification" for a future ROI.

In many cases, the first product that is being developed is sometimes nothing more than a trial balloon, designed to prove or to disprove a certain thesis. The underlying logic is: why do we need to invest in the proper architecture / infrastructure if we don't know whether this product has any future at all?

While the logic of the above assumption is correct, and, one doesn't really progress with validating her/his product-market-fit assumptions by investing in the infrastructure for the product - the problems arise when the code actually sticks around.

After all, unless explicitly designated, code that someone developed rarely gets thrown away completely. The solution may undergo a pivot, the company may change positioning or messaging for the product, but the technological investments may actually remain. Not to mention the case where the original thesis, or a certain part of it, gets actually proven and the company continues developing the idea.

What happens then? Your team (hopefully, a collection of capable individuals) has been running amok developing the product functionality, they have actually created something that looks and acts like the real deal, but its foundation is flaky.

It is very difficult to pause and make a re-factoring effort at the time when your product is starting to gain traction. After all - everyone expects the opposite to happen - you should floor the pedal in developing the features and conquer the world.

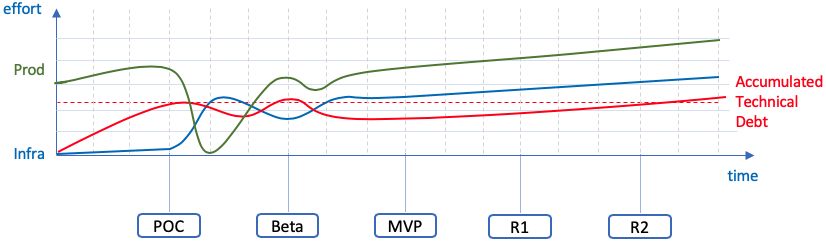

Below diagram explains (schematically) what can happen in this case:

The X Axis represents the timeline (with major project/product milestones, such as POC, Beta, MVP, First Full Release and Second Full Release) whereas the Y Axis represents the effort (and, implicitly, the progress) on either the product debt or the technical debt (Infrastructure / Architecture) fronts.

As described above, we start by investing most of our efforts and resources (that keep growing as our organization grows) on the product front, while convincing ourselves that we will gradually increase the infra investment as the product matures. By the time the product reaches its second significant release, we are expecting to be able to make a significant leap in proper technological foundation.

Sounds nice in theory, right? Let's layer the accumulating technical debt and the acceptable technical debt/quality on this graph to see:

We can clearly see the red line of the Accumulated Technical Debt climbing (why wouldn't it, when there is no sufficient investment) and crossing the dotted red line of the Acceptable Technical Debt (that, surely, doesn't have to be zero) at a certain point.

In this specific graph, this point is between Beta and MVP milestones. It is an example, of course, and, depending on the complexity of your technology and/or the technical acumen of your team, this point can shift to the right. Still, more often than not, this takes place and starts hurting your business at the stage where the business cannot afford this.

Even the optimistic part of this graph, showing that the technical debt starts decreasing after an effort was invested, is very questionable. Who knows if the organization will be able to support the cost of the investment, and who can estimate the impact of providing a product with a technical debt above the acceptable level?

In a nutshell, while all the proponents of this approach will claim that the beast is not as scary as it looks, the author of this article saw (by far) more companies/product teams that either failed, or got crippled by it, than those who actually managed the reap its illusive benefits.

Recommendation: Beware of Greeks bearing gifts. If choosing to go down this route, be very tight with your hand on the pulse of your technical debt.

2⃣ Throwaway POC, then Build the Real Product with Infrastructure

This approach sounds very sensible and easy to implement: all you do is define that your original code is going to have one purpose only - proving that the idea works - and then throw it away and write the real thing.

In theory, the approach works, if you have enough discipline to stick to it. Your investment in the lifelike POC will, hopefully, allow you to prove the product-market-fit, and then, armed with it, you can go and build the real product.

The investment / progress graph of such an approach may look like this:

The investment in the product features during the POC stage, hopefully, gives us the required confidence in the product-market fit. Then, we start developing the real product (this time investing first in the proper infrastructure and architecture, and then piling up the product features). We are further assuming that this work can be split between the Beta and the MVP milestones, delivering a properly-implemented MVP.

Lets layer the Technical Debt accumulation on top of this graph and we will receive the following:

The technical debt reaches unacceptable level quite quickly during the POC, which is fine by us as the POC gets discarded anyway. What happens after that (and the graph shows quite extreme assumptions) is that it is pushed down by the infra/architecture efforts during Beta and MVP stages and stays at the acceptable level all the way until the product evolves far enough from its original purpose - somewhere in the future. Again, depending on the complexity vs flexibility and volatility, the time axis could look quite different.

In theory - this approach makes everyone happy. In practice, in order to succeed, it requires a very adamant engineering team that will really throw away the prototype code and the business team that will understand the delay in Beta/MVP stages because of that. What is the alternative? Getting the same as our #1 approach, but with a higher technical debt (because the initial stages of the POC were developed under the assumption that it'd be thrown away, and here it is - sticking around).

Recommendation: Not all that glitters is gold. If this works, it is a solid strategy, but it is enough that one of the parties involved blinks and it can turn into a disaster.

3⃣ Infrastructure First, then Product, Continuous Refactoring

In recent years, over-simplified interpretation of The Agile Manifesto has motivated people to shun from making large up-front investments in software infrastructure prior to developing a working product. After all, if we should all embrace changing requirements (even late in the development), as well as having our highest priority to satisfy the customer, then investing in health and stability of our own infrastructure isn't necessarily the best thing to do. Delivering more customer-facing features is. Right?

Actually - wrong. Our customers, first and foremost, care about getting a stable, scalable and well-built product, and the fact that we expect requirement changes and will demand (from ourselves) to deliver response to these quickly, mandates that investing in a solid infrastructure and architecture is, actually, on a critical path to the main principles of the manifesto.

While, in theory, this delays the delivery of the first end-to-end POC to the potential customers, with a slightly larger (or more professional team) this could be mitigated. The graph of such an approach may look like the below:

While this graph also hides some assumptions, it shows the biggest desired benefit of the approach: the fact that the technical debt is constantly managed and, hopefully, doesn't cross the line of an acceptable debt in the foreseeable future.

Sure, skeptics can claim that this graphical representation is biased and that the approach hides potential of over-investing in the infrastructure and under-delivering on the product front. This isn't entirely incorrect. This approach is not a silver bullet and requires close management, just like anything else.

One important benefit that it introduces is that the technical debt is being managed (and kept at bay) from the very beginning of the product lifecycle. After all, keeping something at bay continuously vs allowing it to spike and then trying to calm it down is (arguably) going to be more cheap in the long run.

Introducing such an approach as a part of the organizational culture also cultivates pride in one's work and its deliveries. It doesn't exclude the possibility of a pragmatic decision to postpone certain infrastructure investments to future product milestones.

As previously, depending on the complexity of the solution, initial investment in the infrastructure (and the anticipated delay in functional delivery) can be higher or lower.

Recommendation: There's only one chance to start things the right way. Each situation may have its own right or wrong, but combining the desire to build a solid product with strong business connection and guidance, will, probably, provide the best results. There is no shame in admitting that not everything can always be done properly under all possible constraints and in choosing one's battles.

Top comments (0)