I think choosing whether or not you need another web animation library in your life is a little bit like dating. It’s awkward and hyper personal and a bit irrational. And you might be really hesitant to do something new if it feels like you’ve already adapted your whole life to something like Greensock or plain CSS.

As Bryan Braun’s Bouncy Ball project demonstrates, there are at least 20 different ways to animate a two-dimensional blob on the web. And the funny thing to me isn’t how many options the project documents — but pretty much any single one can be used to move a blob in the exact same way.

If the bouncy ball test parameters were different — if there were hundreds of moving blobs, each with its own independent velocity, and some form of randomness that contributed to entirely different motion paths for each individual ball — there might be a more clear winner.

More than likely, the winner would be canvas: because a website can get pretty dang slow when countless nodes that are a part of a DOM tree are moving in a million complex and continually-evolving ways. (And this is especially true for mobile users!)

But web performance aside, it’s not always so easy to delineate what does or doesn’t make sense for a creative project. Your mileage may vary, and you may hate the things that I love.

So this is more or less just an abbreviated history of my personal experience with different approaches to web animation.

GreenSock

You always remember your first love, right? This one was mine. It’s commonly referred to as GSAP, and I discovered it the summer I quit my career in publishing and began dreaming of doing weirder, more creative things.

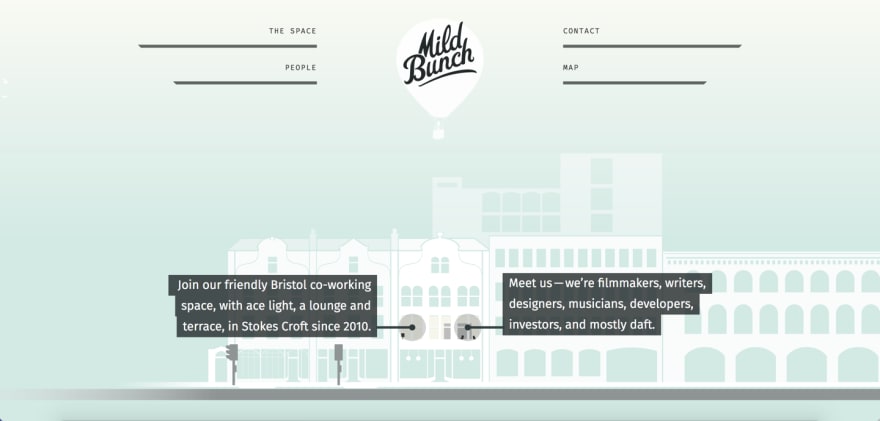

The first weird, creative thing that I discovered built with it was definitely the homepage for Mild Bunch, a coworking space in Bristol, which seamlessly blends gifs into GreenSock-driven animations.

If you’re patient and watch for it, you can catch several different events unfold: including a hot air balloon that drifts away, a flock of birds, a dog walker, a child on a scooter, and a cyclist.

Carefully sequenced, animated timelines like this are often what GreenSock is known and loved for. It can also animate html elements along bezier motion paths; morph between disparate shapes; normalize browser quirks; and a swiss-army-knife oddity of other tasks.

d3

Learning d3 came next for me, and it initially made a lot of sense. It’s an open-source tool and ubiquitous to online data visualization. And after several years in print publishing, using it to pivot my career into more interactive forms of journalism felt like a somewhat happy accident. Like tripping on the sidewalk in a romcom and accidentally discovering your one true love.

Except, d3 probably isn’t it for me. When I tried to learn it, I was still struggling with basic Javascript fundamentals. I couldn’t manage to do much without adding an additional charting library on top of d3. I’m also still not sure I enjoy charts as much as I just inherently feel like I should.

But d3 is a powerful thing that can definitely be used creatively — and an excellent example of that is A Visual Introduction to Machine Learning.

If you’re interested in learning more about the interaction design theory behind it, Tony Chu gave a talk about the project at OpenVis Conf called Animation, Pacing, and Exhibition.

CSS

If I can carry on the whole weird theme of comparing romance to web animation without losing too many readers, how I feel about CSS animation is nothing short of intimate and intense best-friend love. The kind of love embodied by Abbi and Illana on Broad City, or even moreso by Amy and Molly of Booksmart —

Because this is a very nerdy kind of joy. And there’s something wildly pleasing about being able to draw or even hand-write simple svg shapes (or even just divs) and then animate them with css transforms.

Lynn Fisher’s A Single Div project captures much of how silly and wonderful of a style it can feel, with only (as the name implies) a single div and a bit of CSS.

Framer Motion

Sometimes you want to be challenged, and for me recently that’s involved learning Framer Motion. Which isn’t to say it’s difficult to use: the React animation library has a simple, declarative syntax that’s convenient for one-off animations and yet still flexible enough for more complex orchestration.

I’ve been most excited the past few months about how simple it is use asynchronous callbacks from my own custom hooks — written with web platform APIs like Intersection Observer — to affect the state and velocity of a scroll-based animation.

I’m also really excited to experiment with features that include gesture recognition and an accessibility-focused hook called useReducedMotion, and some of the more creative applications of spring and inertia-driven animation.

Which is probably just to say, in the parlance of an old Hollywood talkie, if you’re a creative soul with a penchant for React, I think Framer Motion is nothing short of a fast-talking Bette Davis: a no-nonsense, dependable dame with impeccable wit.

WebGL / Canvas / three.js

I repeatedly ignored these approaches to animation for years before taking a class with Matt Deslaurier last fall on AdvancedWebGL and Shaders at Frontend Masters. Not necessarily because I didn’t think canvas or the 3d applications of Three.js were interesting.

I was mostly just super intimidated.

And I didn’t realize that it was possible to use everything I knew and loved about frontend web development and apply it to in-person, interactive installations — not until meeting Deslaurier and discovering he does just that with projects like N Dimension.

I'm probably going to be in a very shy, staring-at-my-crush-from-behind-a-bush kind of love with this for a little bit, but I've always wanted to experiment with mixing generative design with interaction.

So with any luck, this might just be the accountability I need to pursue it.

Top comments (0)