overview

ES6 provides two new ways of declaring variables: let and const, which mostly replace the ES5 way of declaring variables, var.

let

let works similarly to var, but the variable it declares is block-scoped, it only exists within the current block. var is function-scoped.

In the following code, you can see that the let-declared variable tmp only exists inside the block that starts in line A:

function order(x, y) {

if (x > y) { // (A)

let tmp = x;

x = y;

y = tmp;

}

console.log(tmp===x); // ReferenceError: tmp is not defined

return [x, y];

}

const

const works like let, but the variable you declare must be immediately initialized, with a value that can’t be changed afterwards.

const foo;

// SyntaxError: missing = in const declaration

const bar = 123;

bar = 456;

// TypeError: `bar` is read-only

Since for-ofcreates one binding (storage space for a variable) per loop iteration, it is OK to const-declare the loop variable:

for (const x of ['a', 'b']) {

console.log(x);

}

// Output:

// a

// b

Ways of declaring variables

The following table gives an overview of six ways in which variables can be declared in ES6

Block scoping via let and const

Both letand constcreate variables that are block-scoped – they only exist within the innermost block that surrounds them. The following code demonstrates that the const

- declared variable

tmponly exists inside the block of theifstatement:

function func() {

if (true) {

const tmp = 123;

}

console.log(tmp); // ReferenceError: tmp is not defined

}

In contrast, var-declared variables are function-scoped:

function func() {

if (true) {

var tmp = 123;

}

console.log(tmp); // 123

}

Block scoping means that you can shadow variables within a function:

function func() {

const foo = 5;

if (···) {

const foo = 10; // shadows outer `foo`

console.log(foo); // 10

}

console.log(foo); // 5

}

const creates immutable variables

Variables created by letare mutable:

let foo = 'abc';

foo = 'def';

console.log(foo); // def

Constants, variables created by const, are immutable – you can’t assign different values to them:

const foo = 'abc';

foo = 'def'; // TypeError

Pitfall: constdoes not make the value immutable

const only means that a variable always has the same value,but it does not mean that the value itself is or becomes immutable. Forexample, objis a constant, but the value it points to is mutable – we can add a property to it:

const obj = {};

obj.prop = 123;

console.log(obj.prop); // 123

We cannot, however, assign a different value to obj:

obj = {}; // TypeError

If you want the value of objto be immutable, you have to take care of it, yourself. For example, by freezing it:

const obj = Object.freeze({});

obj.prop = 123; // TypeError

Pitfall: Object.freeze() is shallow

Keep in mind that Object.freeze()is shallow, it only freezes the properties of its argument, not the objects stored in its properties. For example, the object objis frozen:

const obj = Object.freeze({ foo: {} });

obj.bar = 123

TypeError: Can't add property bar, object is not extensible

obj.foo = {}

TypeError: Cannot assign to read only property 'foo' of #<Object>

But the object obj.foois not.

> obj.foo.qux = 'abc';

> obj.foo.qux

'abc'

const in loop bodies

Once a const variable has been created, it can’t be changed. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t re-enter its scope and start fresh, with a new value. For example, via a loop:

function logArgs(...args) {

for (const [index, elem] of args.entries()) { // (A)

const message = index + '. ' + elem; // (B)

console.log(message);

}

}

logArgs('Hello', 'everyone');

// Output:

// 0. Hello

// 1. everyone

There are two constdeclarations in this code, in line A and in line B. And during each loop iteration, their constants have different values.

The temporal dead zone

A variable declared by letor const has a so-called temporal dead zone (TDZ): When entering its scope, it can’t be accessed (got or set) until execution reaches the declaration. Let’s compare the life cycles of var-declared variables (which don’t have TDZs) and let- declared variables (which have TDZs).

The life cycle of var-declared variables

varvariables don’t have temporal dead zones. Their life cycle comprises the following steps:

- When the scope (its surrounding function) of a

varvariable is entered, storage space (a binding) is created for it. The variable is immediately initialized, by setting it toundefined - When the execution within the scope reaches the declaration, the variable is set to the value specified by the initializer (an assignment) – if there is one. If there isn’t, the value of the variable remains

undefined.

The life cycle of let-declared variables

Variables declared via let have temporal dead zones and their life cycle looks like this:

- When the scope (its surrounding block) of a

letvariable is entered, storage space (a binding) is created for it. The variable remains uninitialized. - Getting or setting an uninitialized variable causes a

ReferenceError. - When the execution within the scope reaches the declaration, the variable is set to the value specified by the initializer (an assignment) – if there is one. If there isn’t then the value of the variable is set to

undefined.

const variables work similarly to let variables, but they must have an initializer (i.e., be set to a value immediately) and can’t be changed.

Examples.

Within a TDZ, an exception is thrown if a variable is got or set:

let tmp = true;

if (true) { // enter new scope, TDZ starts

// Uninitialized binding for `tmp` is created

console.log(tmp); // ReferenceError

let tmp; // TDZ ends, `tmp` is initialized with `undefined`

console.log(tmp); // undefined

tmp = 123;

console.log(tmp); // 123

}

console.log(tmp); // true

If there is an initializer then the TDZ ends after the initializer was evaluated and the result was assigned to the variable:

let foo = console.log(foo); // ReferenceError

The following code demonstrates that the dead zone is really temporal (based on time) and not spatial (based on location):

if (true) { // enter new scope, TDZ starts

const func = function () {

console.log(myVar); // OK!

};

// Here we are within the TDZ and

// accessing `myVar` would cause a `ReferenceError`

let myVar = 3; // TDZ ends

func(); // called outside TDZ

}

typeof throws a ReferenceError for a variable in the TDZ

If you access a variable in the temporal dead zone via typeof, you get an exception:

if (true) {

console.log(typeof foo); // ReferenceError (TDZ)

console.log(typeof aVariableThatDoesntExist); // 'undefined'

let foo;

}

Why? The rationale is as follows: foo is not undeclared, it is uninitialized. You should be aware of its existence, but aren’t. Therefore, being warned seems desirable.

Furthermore, this kind of check is only useful for conditionally creating global variables. That is something that you don’t need to do in normal programs.

let and const in loop heads

The following loops allow you to declare variables in their heads:

forfor-in

- for-of

To make a declaration, you can use either var, let or const. Each of them has a different effect, as I’ll explain next.

for loop

var -declaring a variable in the head of a for loop creates a single binding (storage space) for that variable:

const arr = [];

for (var i=0; i < 3; i++) {

arr.push(() => i);

}

arr.map(x => x()); // [3,3,3]

Every iin the bodies of the three arrow functions refers to the same binding, which is why they all return the same value.

If you let-declare a variable, a new binding is created for each loop iteration:

const arr = [];

for (let i=0; i < 3; i++) {

arr.push(() => i);

}

arr.map(x => x()); // [0,1,2]

This time, each i refers to the binding of one specific iteration and preserves the value that was current at that time. Therefore, each arrow function returns a different value.

constworks like var, but you can’t change the initial value of a const-declared variable:

// TypeError: Assignment to constant variable

// (due to i++)

for (const i=0; i<3; i++) {

console.log(i);

}

Getting a fresh binding for each iteration may seem strange at first, but it is very useful whenever you use loops to create functions that refer to loop variables.

for-of loop and for-in loop

In a for-of loop, varcreates a single binding:

const arr = [];

for (var i of [0, 1, 2]) {

arr.push(() => i);

}

arr.map(x => x()); // [2,2,2]

constcreates one immutable binding per iteration:

const arr = [];

for (const i of [0, 1, 2]) {

arr.push(() => i);

}

arr.map(x => x()); // [0,1,2]

let also creates one binding per iteration, but the bindings it creates are mutable.

The for-in loop works similarly to the for-of loop.

Why are per-iteration bindings useful?

The following is an HTML page that displays three links:

- If you click on “yes”, it is translated to “ja”.

- If you click on “no”, it is translated to “nein”.

- If you click on “perhaps”, it is translated to “vielleicht”.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<div id="content"></div>

<script>

const entries = [

['yes', 'ja'],

['no', 'nein'],

['perhaps', 'vielleicht'],

];

const content = document.getElementById('content');

for (const [source, target] of entries) { // (A)

content.insertAdjacentHTML('beforeend',

`<div><a id="${source}" href="">${source}</a></div>`);

document.getElementById(source).addEventListener(

'click', (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

alert(target); // (B)

});

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

What is displayed depends on the variable target (line B). If we had used var instead of const in line A, there would be a single binding for the whole loop and target would have the value 'vielleicht', afterwards. Therefore, no matter what link you click on, you would always get the translation 'vielleicht'.

Thankfully, with const, we get one binding per loop iteration and the translations are displayed correctly.

Parameters as variables

Parameters versus local variables

If you let-declare a variable that has the same name as a parameter, you get a static (load-time) error:

function func(arg) {

let arg; // static error: duplicate declaration of `arg`

}

Doing the same inside a block shadows the parameter:

function func(arg) {

{

let arg; // shadows parameter `arg`

}

}

In contrast, var-declaring a variable that has the same name as a parameter does nothing, just like re-declaring a var variable within the same scope does nothing.

function func(arg) {

var arg; // does nothing

}

function func(arg) {

{

// We are still in same `var` scope as `arg`

var arg; // does nothing

}

}

Parameter default values and the temporal dead zone

If parameters have default values, they are treated like a sequence of letstatements and are subject to temporal dead zones:

// OK: `y` accesses `x` after it has been declared

function foo(x=1, y=x) {

return [x, y];

}

foo(); // [1,1]

// Exception: `x` tries to access `y` within TDZ

function bar(x=y, y=2) {

return [x, y];

}

bar(); // ReferenceError

Parameter default values don’t see the scope of the body

The scope of parameter default values is separate from the scope of the body (the former surrounds the latter). That means that methods or functions defined “inside” parameter default values don’t see the local variables of the body:

const foo = 'outer';

function bar(func = x => foo) {

const foo = 'inner';

console.log(func()); // outer

}

bar();

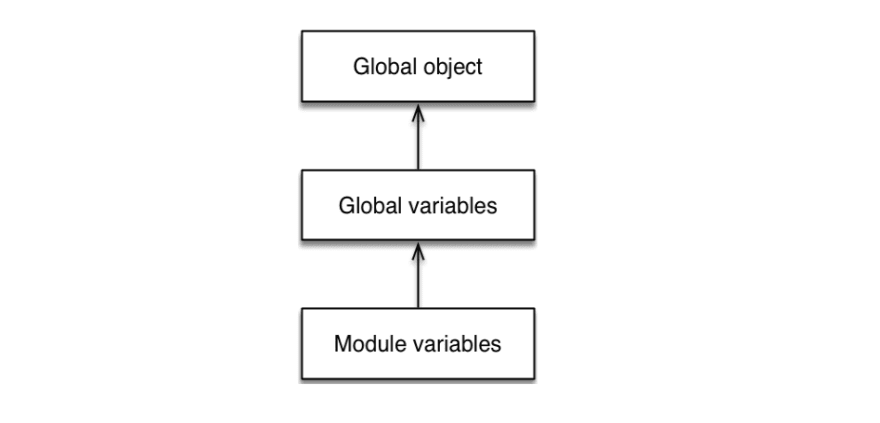

The global object

JavaScript’s global object (window in web browsers, globalin Node.js) is more a bug than a feature, especially with regard to performance. That’s why it makes sense that ES6 introduces a

distinction:

-

All properties of the global object are global variables. In global scope, the following declarations create such properties:

-

vardeclarations - Function declarations

-

-

But there are now also global variables that are not properties of the global object. In global scope, the following declarations create

such variables:-

letdeclarations -

constdeclarations - Class declarations

-

Note that the bodies of modules are not executed in global scope, only scripts are. Therefore, the environments for various variables form the following chain.

Function declarations and class declarations

Function declarations…

- are block-scoped, like

let. - create properties in the global object (while in global scope), like

var. - are hoisted: independently of where a function declaration is mentioned in its scope, it is always created at the beginning of the scope.

The following code demonstrates the hoisting of function declarations:

{ // Enter a new scope

console.log(foo()); // OK, due to hoisting

function foo() {

return 'hello';

}

}

Class declarations…

- are block-scoped.

- don’t create properties on the global object.

- are not hoisted.

Classes not being hoisted may be surprising, because, under the hood, they create functions. The rationale for this behavior is that the values of their extends clauses are defined via expressions and those expressions have to be executed at the appropriate times.

{ // Enter a new scope

const identity = x => x;

// Here we are in the temporal dead zone of `MyClass`

const inst = new MyClass(); // ReferenceError

// Note the expression in the `extends` clause

class MyClass extends identity(Object) {

}

}

Hope this blog helped you learn about variables and scoping a little better.

Top comments (0)