Introduction

One of the most challenging things when working on a project is the management of technical debt.

Technical debt is a term used to describe the accumulation of decisions in the code which aren’t perfect and can make further development harder when not addressed promptly. Obviously, these decisions never happen consciously, but, rather, they surface as a natural consequence of the iterative nature of the development process.

Many developers, managers, teams and companies, wrongly believe that such a thing will never occur if proper methodologies are in place, or, they believe that such thing will certainly only happen on a very large and complex project, orchestrated by a team of many engineers over a long period of time. This vision couldn’t be further away from reality, and, in fact, on a daily basis, companies and businesses fail as they succumb to endless technical debt. Here’s a harsh reality check: the next feature planned will potentially add technical debt. It doesn’t take a large team of people or a very complex project, all it takes is one feature, and another, and another… and, before you know it, the codebase which looks really nice on a “per-feature” overview, becomes more rigid, harder to extend, costly to maintain and new developers will struggle to grasp the flow of the code. Leave this unaddressed over a long period of time, on larger scale projects, and you can imagine how difficult it is.

In fact, I want to advocate, that every line of code potentially written can add overhead to a codebase that can later (or immediately) be singled out and addressed in order to keep your code clean and maintainable.

I have been working in and out on this project alone, as a single developer, for a few months already, it’s a very small effort essentially directed towards learning new frameworks and exercising some API usage and yet, even a super simple project like this already has accumulated a lot of technical debt. Let’s see the hotspots and how we can address them.

Hotspots in our codebase

As a project starts, very little is known about…literally everything. The business requirements are usually vague to non-existent, current decisions are hinging on extremely weak foundations and ideas are scattered all over the place, so, starting development at this stage, is nothing more than an exercise in scaffolding and testing out ideas or even a certain technology stack. Things need to be materialized to be measured and later improved, so, any code written now, will be worse than all the code written later, and yet, as developers, we need to start and iterate.

Writing good, maintainable code is nothing more than iterating badly specified requirements, while applying good design principles.

For instance, the current application is working as a simple recipe aggregator through usage of the Spoonacular API. All the design decisions that will be made from now on, will rely on the fact that this is what the application is currently doing, and they will only be valid under this particular context.

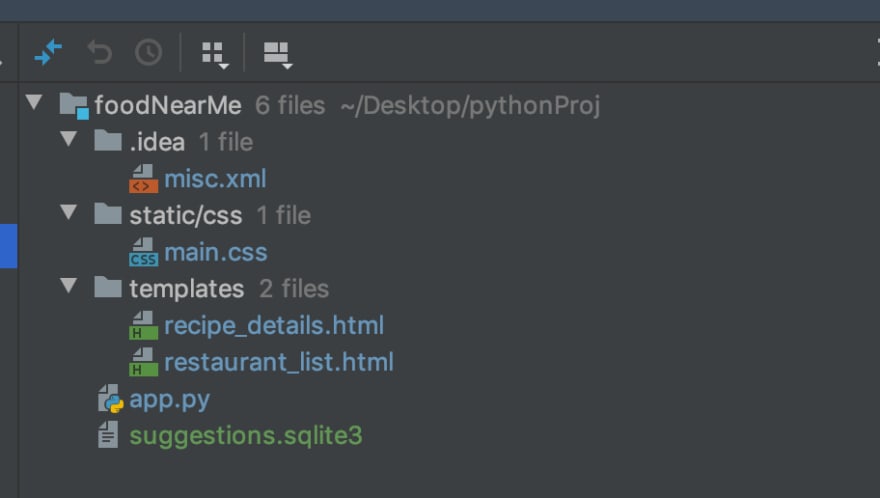

However, it started differently in my head. Initially, I had planned to develop a simple app that leveraged different APIs and used geolocation to provide the user with “live” on-the-spot restaurants around you, as you searched for specific cuisines or ingredients. In fact, let’s look at the current version of the folder structure of the project:

The main template file is still called restaurants_list.html and we have a recipe_details.html. This is completely wrong, since we have nothing to do with restaurants at the moment, it’s all about ingredients and recipes, so, let’s go ahead and do our first refactoring: Rename file.

The rename refactoring

Obviously, if we rename our template file to recipes_list.html the intent of the file will be much more clear for anyone who will open it, since, all we do there is essentially configuring a template to show a list of recipes to the final user.

The usefulness of this refactoring can’t be stressed enough: it’s probably the highest on my list in terms of effectiveness: it can be done very easily on any modern IDE, and the dividends are enormous: domain-context and English words are the best ways to abstract away the complexity of the code and make other developers’ lives easier when working with our code.

The other huge advantage of this refactoring is it’s applicability: you can rename anything that has a named identifier in the code: files, packages, classes, functions, interfaces, variables, even annotations. Maintaining good, concise, descriptive and easy to read names across all these locations is a great way to ensure that your code is more readable and hence more maintainable. Consider the following:

def f(x):

[x for x in bd if x.tr>100.0]

versus:

def employeesWithLargestRevenue(entity_in_db):

[employee for employee in EmployeesTable if employee.totalRevenue > 100.0]

Both snippets are doing exactly the same thing, but, one is so much clearer than the other, and, the only thing we did was change the names of the variables and functions used. It’s very easy to do and very nice with regards to readability.

Inline when you can, extract constants when meaningful

Taking our current codebase as an example, here’s what we have in our restaurant_input_adapter.py file:

def convert_input(ingredients):

ingredients = "".join(ingredients.split())

converted = ",".join(map((lambda s: "+" + s), ingredients.split(",")))[1:]

return converted

This doesn’t look too bad at a first glance, we have some decent function name, the parameter is quite explicit and the actual work of the function itself is also clear from the name, and, from reading what the function is doing. (as a side-note, note that this is as complex as demanded by the API itself which requires a somewhat cumbersome format of its arguments for a specific endpoint – this is not our problem and we can’t avoid it since we need to consume the API, but, when writing code it illustrates that probably the original authors of the API didn’t thought it through completely)

However, we see that we have the variable converted in there, that is simply being returned. It’s unnecessary, and it can be immediately inlined:

def convert_input(ingredients):

ingredients = "".join(ingredients.split())

return ",".join(map((lambda s: "+" + s), ingredients.split(",")))[1:]

We just reduced our line count by 1. It’s not a lot, of course, in fact, it’s arguably “nothing”, but, if you do this frequently across multiple functions, over time, it can easily start to pay off in the long run. Every line you remove is a line that reduces the chances of introducing bugs while increasing reading speed for your peers. Make a habit out of this, and you won’t be able to stop doing it!

Regarding literal constants

Previously, this is what we had:

def employeesWithLargestRevenue(entity_in_db):

[employee for employee in EmployeesTable if employee.totalRevenue > 100.0]

What is that 100.0 doing there? What does it mean? Is it reused across multiple semantically equivalent places? Can we increase clarity somehow?

QUARTERLY_THRESHOLD = 100.0

def employeesWithLargestRevenue(entity_in_db):

[employee for employee in EmployeesTable if employee.totalRevenue > QUARTERLY_THRESHOLD]

Turns out that yes, we can, the 100.0 was not any arbitrary value, in our domain it actually meant the minimum value of revenue needed to reach in a quarter to be qualified as an employee with high revenue. Now the code is much clearer and it has the added bonus that if this constant was being used across the codebase, our chances of forgetting to update it somewhere may requirements change, just became 0. You change the value of the constant, and everything works.

Don’t get tied in your own code: use dependency injection when possible

Here is something that we did well on our first try:

Remember the autocomplete logic we had written? When we call it from our HTML, we pass our array of ingredients like this:

autocomplete(document.getElementById("autocomplete"), ingredients);

This is really nice, because, now, this is simply an in-memory data structure, tomorrow, we can receive it from an external service, load it from a database, import it from a file, etc, and our code won’t be tied to any specific implementation, what we do is we inject it as a parameter to our function and our code immediately becomes more robust and easier to reuse. Seek to use dependency injection where possible.

Follow your IDE

IntelliJ, Eclipse, VS Code, among other IDEs are getting smarter and better with every new release, so, following suggestions coupled with your experience can go a long way. Some examples can include:

Break up long and complex methods in smaller, more cohesive ones;

Use extract interface, method and/or move method, to structure your code in a more sensible way;

Rename ANYTHING in your code to focus on increasing readability;

Code for today and now, improve tomorrow!

If you apply these rules daily as a part of your coding work, the quality will start rising and it will keep steady as you will keep fostering new and better habits thanks to your best practices and will enter on a very good upward spiral. Keep at it and quality will rise.

Conclusion

I hope you liked reading and understood the importance of continuous refactoring and why it is so important to follow these simple rules to increase code quality.

Debt is always assured, and the only way to pay it off is by relentlessly refactor and seek the best possible version of your own code.

Stay tuned for more!

Top comments (0)