library(pokedex)

library(tidyverse)

library(knitr)

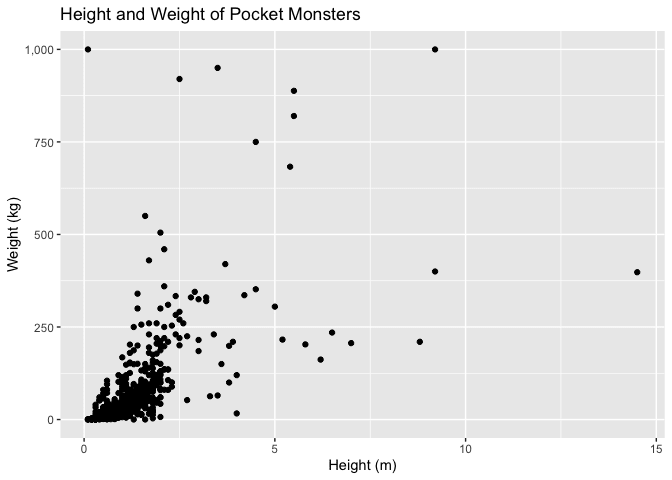

How big is a Pocket Monster?

Pokemon is a combination of ‘Pocket’ and ‘Monster’. So they’re all

pretty small right? Not quite.

scale_format <- scales::number_format(accuracy = 1, big.mark = ",")

pokemon %>%

ggplot(aes(x = height, y = weight)) +

geom_point() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scale_format) +

labs(title = "Height and Weight of Pocket Monsters",

x = "Height (m)",

y = "Weight (kg)")

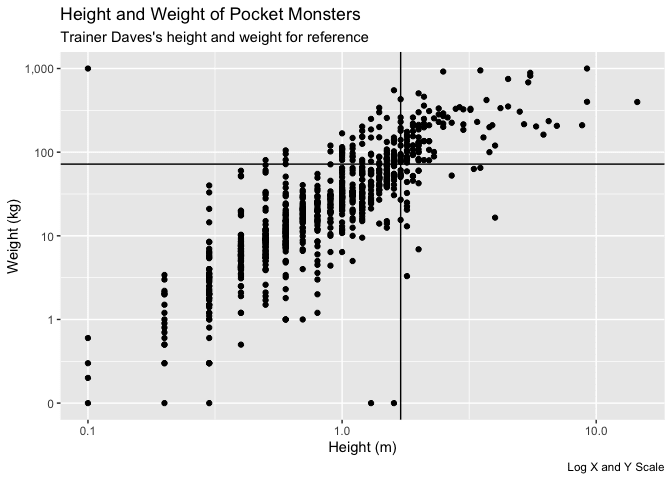

Maybe we need to work on this graph a little. Let's make it log scaled on

both axis. I’ll put myself in for reference too.

pokemon %>%

ggplot(aes(x = height, y = weight)) +

geom_point() +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1.7) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 72) +

labs(title = "Height and Weight of Pocket Monsters",

subtitle = "Trainer Daves's height and weight for reference",

x = "Height (m)",

y = "Weight (kg)",

caption = "Log X and Y Scale") +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10(labels = scale_format)

So after a log transform of the scales we have a (roughly) linear

relationship. This is what we would expect in real world data. Nothing

with a physical existence can have a 0 or negative measure for these

features. Therefore, thinking of this in terms of average can be

misleading. It will always be ‘long tailed’. It might be a stretch to

refer to them all as Pocket Monsters though.

There’s also clearly a relationship between both height and weight.

Let’s try and capture this in a single feature.

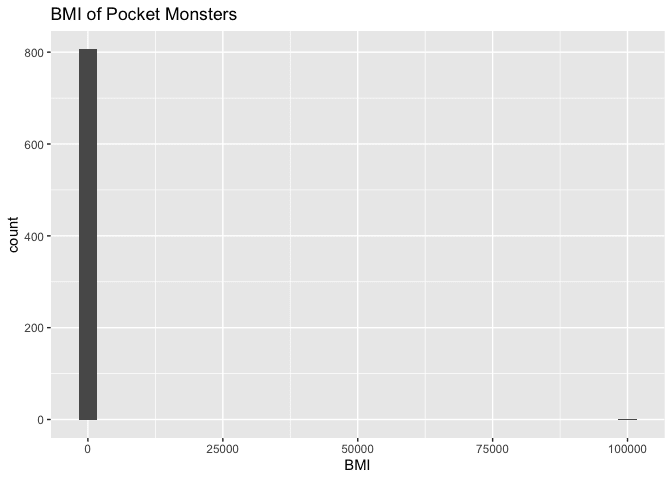

BMI

The body mass index is a simple metric to link height and weight. Let’s

create it for our Pokemon.

BMI <- function(weight, height) {

weight/(height^2)

}

pokemon %>%

mutate(BMI = BMI(weight = weight, height = height)) -> pokemon

pokemon %>%

ggplot(aes(x = BMI)) +

geom_histogram() +

labs(title = "BMI of Pocket Monsters")

Well, that’s something of a surprise. Looking at the scatter plots from

earlier, there is something in the data set that is very small, but also

extremely heavy. Let’s try and work out what that is.

pokemon %>%

arrange(desc(BMI)) %>%

select(name, height, weight, BMI, genus) %>%

top_n(10, BMI) %>%

kable()

| name | height | weight | BMI | genus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmoem | 0.1 | 999.9 | 99990.0000 | Protostar Pokémon |

| Minior | 0.3 | 40.0 | 444.4444 | Meteor Pokémon |

| Aron | 0.4 | 60.0 | 375.0000 | Iron Armor Pokémon |

| Durant | 0.3 | 33.0 | 366.6667 | Iron Ant Pokémon |

| Clamperl | 0.4 | 52.5 | 328.1250 | Bivalve Pokémon |

| Torkoal | 0.5 | 80.4 | 321.6000 | Coal Pokémon |

| Cacnea | 0.4 | 51.3 | 320.6250 | Cactus Pokémon |

| Munchlax | 0.6 | 105.0 | 291.6667 | Big Eater Pokémon |

| Sandygast | 0.5 | 70.0 | 280.0000 | Sand Heap Pokémon |

| Beldum | 0.6 | 95.2 | 264.4444 | Iron Ball Pokémon |

There’s no accounting for cosmological battle entities. I’m going to

claim that the Protostar Pokemon is a little out of scope for this and

filter it out. Let’s have a look at what we’re left with.

Dave_BMI <- BMI(weight = 72, height = 1.70)

pokemon %>%

filter(name != "Cosmoem")%>%

ggplot(aes(x = BMI)) +

geom_histogram() +

geom_vline(xintercept = Dave_BMI) +

labs(title = "BMI of Pocket Monsters",

subtitle = "Trainer Dave's BMI for reference",

caption = "Cosmoem removed")

So most Pokemon are actually a little bigger than me, and a few of them

are a lot bigger!

We’ve also realised that some of them might just be very different to

me, like stars, made entirely of metal or rock, or maybe even giant

dragons? Just like in the earlier article, I’m going to pivot the data

so we get a comparison for dual type Pokemon on both their types.

pokemon %>%

filter(name != "Cosmoem") %>%

select(name, type_1, type_2, BMI, height, weight) %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = starts_with("type"),

names_to = "slot",

values_to = "type",

values_drop_na = TRUE

) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = BMI)) +

geom_density() +

geom_vline(xintercept = Dave_BMI) +

facet_wrap(. ~ type, scales = "free") +

labs(title = "Pocket Monster BMI by type",

subtitle = "Trainer Dave's BMI for reference",

caption = "Cosmoem removed")

So it looks like I’m not quite as hefty as Pokemon that are rock, steel,

ice, ground, fighting, dark or dragon. That makes sense. I’m also a bit

more corporeal than fairy or ghost type. Pokemon has some really big

bugs though!

Game Over

We’ve learned quite a few R programming things today. The most obvious

were some ggplot chart tools:

-

geom_vline()andgeom_hline()make 1 dimensional lines at specific points -

geom_histogram()andgeom_density()show the distribution of a single value across mutiple observations -

facet_wrap()can make grouped charts, which are often known as small multiples -

scale_x_log10()andscale_y_log10is an easy way to plot a log axis - the

scalespackage is also useful for formatting the axis labels

Did you also notice the first thing we did with the scales package? In

R you can assign a function to a reference. This means that we don’t

need to repeat ourselves if we want to set it up with the same arguments

multiple times, like with formatting axis with large numbers.

In the tidyverse world we also used the optional arguments in

pivot_longer() to select 2 columns to pivot on, and to drop rows we

create that have NA when the Pokemon only has 1 type.

Most importantly though, we created our own function, and it was easy!

The BMI function we created we used to make a single value,

Dave_BMI, but also to make the whole BMI column for each Pokemon in

the data set! That’s pretty cool.

From 2 known features, weight and height we made one single new

measurement BMI. This an example of something that will come up more

in later posts about machine learning which is called ‘feature

engineering’.

The next article will be going into how the Pokedex package is actually

made, both in trying to design a ‘tidy’ data set, but also how to make a

package in R!

P.S. I know that Pocket Monster is related to the pokeballs they fit in, but that's a less fun title.

Top comments (0)