Honeypots can provide valuable insights into the threat landscape, both in the open internet as well as your internal network. Deploying them right is not always straightforward, just like interpreting any activity on them.

This is part 1 of a series detailing visualization, automation, deployment considerations, and pitfalls of Honeypots.

An extended version of this article and an according talk can be found at Virus Bulletin 2020.

As attacks on internet-facing infrastructure shifted to being mostly automated in recent years, Honeypots lost some of their meaning in detecting novel exploits and attacks on said infrastructure. Combined with the fact that the people running Honeypots usually don’t want to give away details on how they customized them to keep them from being detected, this leads to a situation where the value of running them got upstaged. Although the means of operation of attackers has changed, Honeypots still allow valuable insights into ongoing campaigns, used credentials and distributed payloads.

To uderstand what value Honeypots bring to the table, it is imperative to know, what they are used for.

Basically, Honeypots mimic systems that look vulnerable and therefore are valuable targets for attacks. This can either be a vulnerable looking service (i.e. SSH, Elastic) or client (i.e. Browsers).

The latter emulates a browser to find websites that for example try to execute malicious payloads on clients, like JavaScript Cryptominers or Drive-By-Downloads.

The former emulates a complete server or protocol to find tools, techniques and procedures used by malicious actors. Such Honeypots can be used to uncover for example attacks tailored to overtake publicly accessible IoT devices or ransom unsecured MongoDB instances.

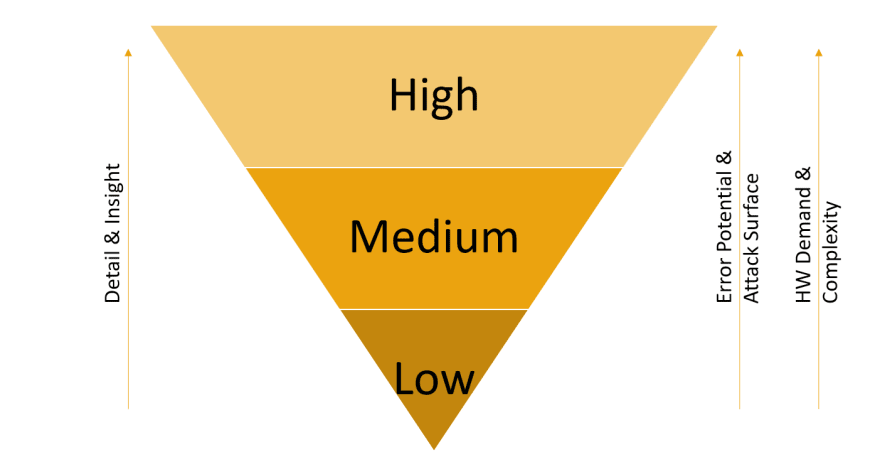

Server-side Honeypots can further be grouped into three categories based on the level of emulation they provide: Low, Medium and High Interaction Honeypots.

Low interaction Honeypots are rather easy to build, as they often emulate only the basic commands of a protocol. For SSH, a low interaction HP can consist only of the login dialog to collect usernames and passwords potentially used in credential stuffing attacks.

Medium interaction Honeypots take this principle a step further and emulate more commands and part of the surrounding system. As an example, the medium interaction HP Cowrie emulates a complete filesystem as well as many integrated system commands like lsof or netstat to look like a fully running system.

Finally, high interaction Honeypots represent a fully functioning implementation of the protocol in question, often made available through a Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) proxy which logs every interaction with the HP. For SSH this is represented by Dockpot, which is a HP that is running a full Linux system in an image, exposing the SSH connection through a MitM proxy that logs all interactions and issued commands. For every connection from a distinct source IP, a new container will be created and kept until a timeout is reached. This not only enabled connection separation but also persistency across connections, as the attacker finds the filesystem with all changes and additions that were conducted during the first connection.

All three groups have their advantages and use cases. While detail and insight grow from using low to high interaction Honeypots, the error potential, attack surface, hardware demand and general complexity increase as well.

Low and Medium interaction HPs are often developed as scripts being run by an interpreter, i.e. Python. While they provide limited insight and are relatively easy to detect, they can be installed on virtually any OS that is able to run a fitting Python distribution. This could be anything ranging from a Raspberry Pi up to fully fledged standalone Hardware or cloud deployments.

High interaction HPs are often based on virtualization or containerization technologies and require a more advanced setup. This includes using sufficiently powerful hardware, configuring the abstraction layer, and setting up VMs or containers.

Therefore, goals, budget, and time constraints should be known before deciding which Honeypot will be deployed.

Top comments (0)