Bugs are an inevitable, unwelcome part of programming. By testing and coding in tandem, you can eradicate a lot of bugs, and have more confidence in your code.

There are different strategies and tools you can employ for testing web applications, I will break these down for you, and test the application from my previous post. Although, I am testing a Spring Boot application, a lot of what I discuss can be applied to any web application written in Java.

- What should we test?

- Unit tests

- Integration Tests

- How many tests are enough?

- Test libraries that you can use

- Testing the application

- Source Code

- Final Words

- References

What should we test?

The focus of this article is writing tests as a developer.

As developers, we write tests while writing code, so we can make more assured progress. Tests give us feedback that we haven't broken something along the way, and that our code works reasonably well. Tests also serve as invaluable "documents" to other developers, and to your future self, to understand what the application does.

Developers typically write unit tests and integration tests. Beyond that, it is typically in the responsibility of Test or Quality Assurance.

Before we go further, let's define what unit tests and integration tests are, so we don't get confused. The terms are open to interpretation! Then, we can touch on what tests you "should" write.

Unit Tests

What most people agree on is that unit tests:

- Focus on a small part of the application.

- Are typically automated and written by developers.

- Are expected to be significantly faster than other kinds of tests.

What is a unit?

Object-oriented programs tend to treat a class as the unit, but not always. It is your decision to define what a unit is. It is not necessary to define a single atomic unit for your entire application, you can encounter situations with different demands.

Sociable or Solitary?

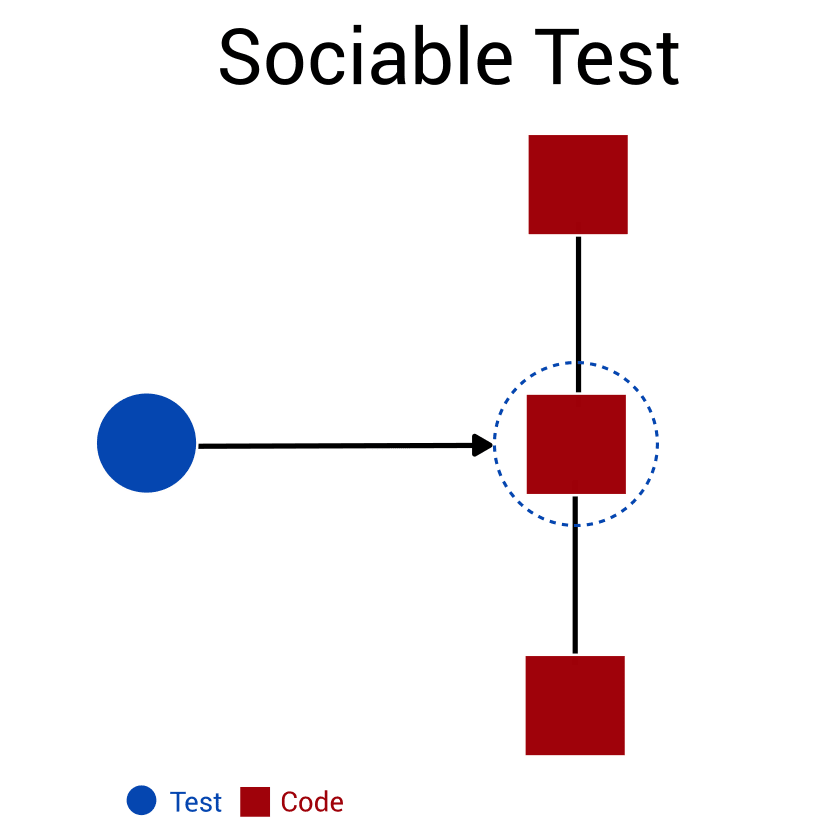

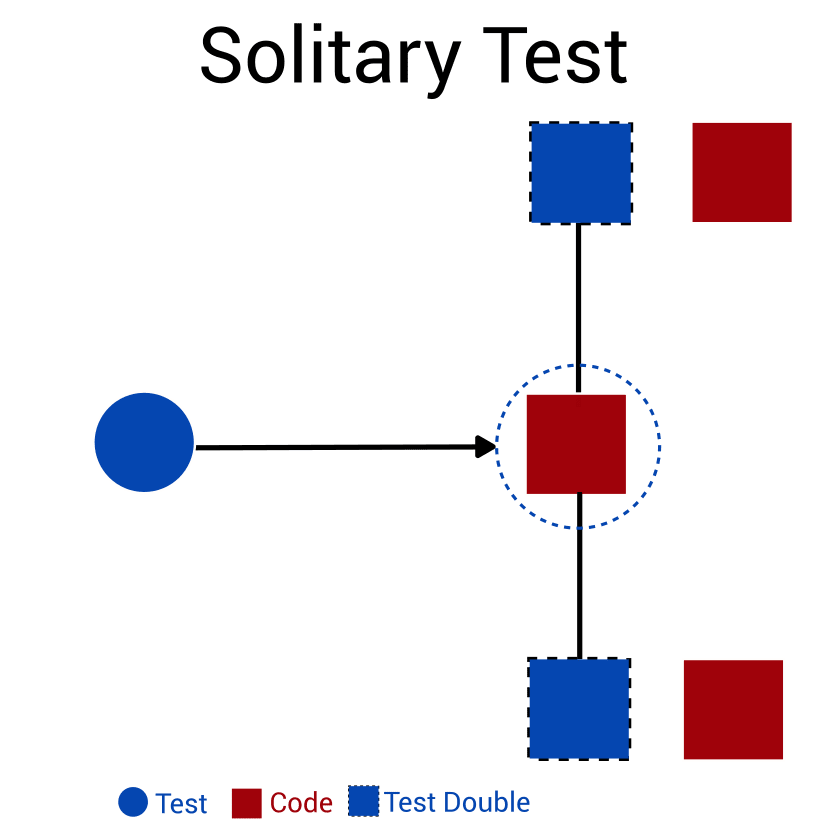

One way to define what your unit of choice is, is to decide if your tests are solitary or sociable.

Sociable tests test a unit and its collaborating units together. Often, for an unit to fulfil its behaviour, it requires collaboration with other units, so this group can serve as "your logical unit" if you wish.

Solitary tests focus on an isolated unit and exclude its collaborating units. This is done by using test doubles (Dummy objects, Stubs, Spies, Mocks, and similar) instead of the collaborating units.

If you want to test your system only using sociable tests, it is not always be pragmatic to do so, you may encounter situations such as asynchronous collaborations (HTTP requests) or concurrent actions (threads), which may require you use a solitary test.

Integration Tests

The line between integration tests and unit tests is debatable. I consider integration testing to be concerned with testing how a group of system units work together with minimal test doubles.

The term integration test gets applied to a variety of scenarios. Below is the spectrum of what an integration test is considered by some people:

- A test that covers multiple “units”. It tests the interaction between these units.

- A test that covers multiple layers of an application. This is a special case of the first case really. For example, in a web application, it might cover the interaction between the service layer and the persistence layer.

- A test that covers a complete path through the application. For example, in a web application, it might cover all types of requests to a specific endpoint such as

/users. - The integration of your entire application.

I consider the maximum scope of integration tests to be scenario 3 above.

Something you should consider with your integration tests is configuration, you may disable or change some options to simplify tests, or to improve the running time of your tests. It is common to create configuration profiles for testing. You need to strike a balance between making quick tests that support your development process, and making realistic tests that are closer to the production environment.

How many tests are enough?

Conventional wisdom was to write mostly unit tests and fewer integration tests. Generally, the more tests you have, the better the chances you have of catching bugs, but it is a case of diminishing returns as you get towards 100% code coverage.

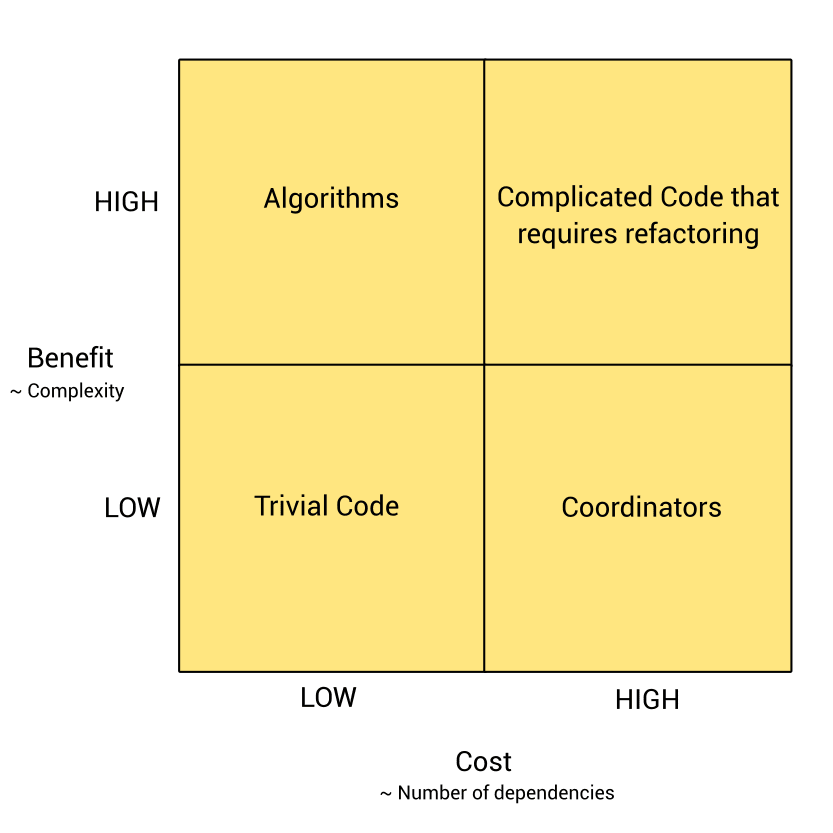

You have to decide how much of your code you will cover with tests based on the various constraints of the project, weighting up the costs and benefits. Steve Sanderson [^3] advocates selective unit testing based on the complexity of the code and the cost of testing it, which is summarised in the diagram below.

Kent Beck advocates writing not too many tests, and for most test to be integration tests [^4].

I tend to agree with Kent Beck, and try to write more integration tests, but I prioritise features, and look to make the right trade-offs between speed and accuracy when deciding to write unit tests or integration tests.

Test libraries that you can use

You can use whatever libraries you want for testing. In the previous post, I spoke about using Spring Initializr to create the project skeleton, by default it includes the spring boot starter test dependency, and excludes the vintage engine module, which is used to support test written in JUnit 3 and 4.

In Maven, the dependency looks like this:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-test</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

<exclusions>

<exclusion>

<groupId>org.junit.vintage</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-vintage-engine</artifactId>

</exclusion>

</exclusions>

</dependency>

This starter dependency combines a compatible collection of testing libraries. It includes:

- JUnit 5: The most popular library for unit testing. This is what most people use to run their tests. JUnit 5 has made some significant changes from previous versions, most notably the annotations have changed. It offers support for the JUnit 3 and JUnit 4 syntaxes through its vintage engine module, include this if you want to use one of those syntaxes. The docs are pretty good, I suggest you read through them to get more familiar with the basics.

-

Mockito: Is used for creating mock objects. It offers a simply API. You can use annotations such as

@Mockfor variables and it will create a mock object for you. -

Hamcrest: Is used to declare "matcher" rules, which are easier to read e.g.

assertThat(Math.sqrt(-1), is(notANumber()));. -

JsonPath: Is used to query JSON objects using path expressions e.g.

$.namewould reference name in{name: "rob oleary, age :20}. -

JSONAssert: Enables you to execute assertions with JSON data in less code e.g.

JSONAssert.assertEquals(expectedJSON, actualJSON, strictMode);. - JacksonTester: Create an object mapper to transform objects to and from JSON.

You will see that different people prefer some libraries and styles over another, or they may mix and match them. So, don't be intimidated if you see test cases that look quite different from what you already are accustomed to, the objectives are the same.

Testing the application

I have made one change to the code from the previous post, I have removed the dummy data from UserController. The code we discuss in this post is available in a new branch in the same github repository called with-tests.

How to Write Test Cases

Every test case should have some form of the following three steps:

- Preparation: Set up all data required to execute a method under test.

- Execution: Execute the actual method under test.

- Verification: Compare the actual behaviour of the method under test to the expected behaviour.

Try to write a test case for every method, covering the happy path (the most common, error-free scenario), and some exceptional scenarios.

Unit Test for User

Testing model classes is generally straightforward.

Should I Test POJOs?

You may have heard of the reference to Plain Old Java Objects (POJOs) before, it usually refers to a very basic class structure, usually a class that just has some attributes, getters, and setters.

Opinions vary on whether you should test POJOs. The argument against testing them is usually that the behaviour is trivial and is unlikely to break. Uncle Bob's personal rule is:

The rule in TDD (Test Driven Development) is "Test everything that could possibly break" Can a getter break? Generally not, so I don't bother to test it. Besides, the code I do test will certainly call the getter so it will be tested.

My personal rule is that I'll write a test for any function that makes a decision, or makes more than a trivial calculation. I won't write a test for

i+1, but I probably will forif (i<0)...and definitely will for(-b + Math.sqrt(b*b - 4*a*c))/(2*a)

The argument for testing POJOs is that you should test the interface; not the implementation. You shouldn't base tests on what the decisions are made within a test, and writing tests for them are a way to ensure method contracts are fulfilled. [^1] Some people want to have high test coverage, so they will test almost everything.

You can decide for yourself whether you want to unit test POJOs.

Writing the Test Class

Using JUnit is sufficient for unit testing, I will only use JUnit 5 for testing User.

- In a maven project, the default location for tests is src/test/java.

- The convention is to name our test classes as "*className*Test", our test class for

Userwould be calledUserTest. You can call it whatever you like! The advantage is when you create a test suite to group together tests, you just include a package, and the default behaviour is that the test runner will include only the tests that have "Test" in the name. - You can include preparation that is common to every test case, and run before each test case, in a "setUp" method annotated with

@Before(JUnit 4) or@BeforeClass(JUnit 5). - You annotate a test case with

@Test, so the test runner will run it. - The most common JUnit 5 assertions are

assertEquals,assertNotEquals,assertTrue, andassertNull. You find these in theorg.junit.jupiter.api.Assertionspackage. - You can include common clean-up tasks run after each test case in a "tearDown" method annotated with

@After(Junit 4) or@AfterClass(JUnit 5).

It is the org.junit.jupiter.api package that you use for testing.

In the setUp method, we create a new User object each time, this ensures that our test cases start with the same default state, and can remain independent of each other. You should not rely on tests being run in a particular order.

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.BeforeEach;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.AfterEach;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import java.util.ArrayList;

public class UserTest {

User testUser1 = null;

@BeforeEach

void setUp() {

testUser1 = createNewUser();

}

@AfterEach

void tearDown() {

testUser1 = null;

}

User createNewUser(){

return new User(1,"Rob OLeary", 33);

}

//naming convention I follow is: MethodName_StateUnderTest_ExpectedBehavior

@Test

void getId_1_ReturnValue(){

Assertions.assertEquals(1, testUser1.getId());

}

//more test cases

}

The test cases are quite simple and shouldn't require explanation. You can choose a naming convention for your methods if you want to, I loosely follow the convention of MethodName_StateUnderTest_ExpectedBehavior.

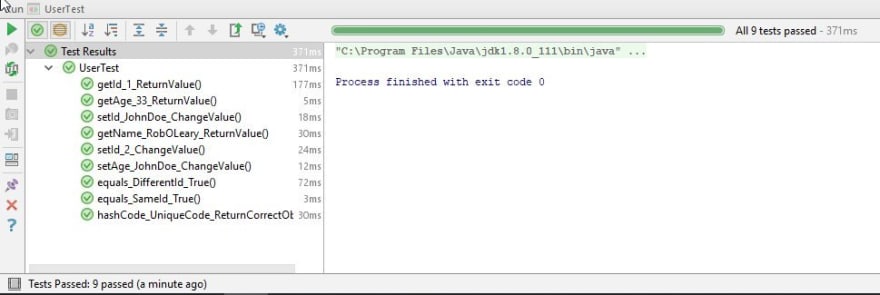

In most IDEs you can run your tests in the same way as you run a class, and it will show a test runner which shows the execution of the various test.

Execution Time for UserTest

The execution time is 371ms for 9 tests. The picture below is what the tester runner looks like in IntelliJ.

Unit test for UserController

To get as close as we can to a solitary unit test, we want to mock the MVC environment, and exclude the embedded server. In our setUp method, we create a Standalone MockMVC and register our controller with it. Think of standalone mode as the minimum environment setup.

For each test, we use our MockMVC instance to perform the mock requests we require, we receive a MockHttpServletResponse in response, which we can use for assertions.

Implicitly, UserController uses the Jackson library for transforming User objects to and from JSON. Because it is a minimum environment, we have to transform our User objects to JSON when required. We use JackonTester for this.

public class UserControllerTest {

private MockMvc mvc;

private JacksonTester<User> jsonUser;

private String basePath = "/users";

private final User TEST_USER = new User(1, "Rob OLeary", 21);

private final User TEST_USER_2 = new User(2, "Angela Merkel", 20);

@BeforeEach

public void setup() {

JacksonTester.initFields(this, new ObjectMapper());

// MockMvc standalone approach

mvc = MockMvcBuilders.standaloneSetup(new UserController()).build();

}

//test cases

}

Test Cases for UserController

For the test assertions, I am using Hamcrest matchers and JacksonTester.

I will explain the test cases for getUser, to give you the gist of how to test yourself.

getUsers (happy path)

This is the happy path for getUsers. In the response, we expect to get all the users as a JSON array, and an OK HTTP Status.

@Test

public void getUsers_2UsersExist_ReturnOK() throws Exception{

//data prep

addUsers();

// execute

MockHttpServletResponse response = mvc.perform(

get(basePath).accept(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON))

.andReturn().getResponse();

// verify

assertThat(response.getStatus()).isEqualTo(HttpStatus.OK.value());

String jsonUser1 = jsonUser.write(TEST_USER).getJson();

String jsonUser2= jsonUser.write(TEST_USER_2).getJson();

String jsonUserArray = "[" + jsonUser1 + "," + jsonUser2 + "]";

assertThat(response.getContentAsString()).isEqualTo(jsonUserArray);

}

- Preparation: We write a helper method

addUsersto create Users to setup data. - Execution: Static imports are used to allow us to call the static methods for making requests. For example,

static import org.springframework.test.web.servlet.request.MockMvcRequestBuilders.get;enables us to create a mock GET request usingget(). We chain methods to shorten our code. - Verify: I use the Hamcrest matchers for the assertions. I build the expected result string using

JacksonTester.

Alternatively, some people using JsonPath for assertions when dealing with JSON, I use JacksonTester because Spring uses Jackson for the transformation functionality, so it a bit closer to the real functionality.

This is the same test case using JsonPath.

/*

These are the related import statements:

import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultMatchers.content;

import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultMatchers.jsonPath;

import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultMatchers.status;

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.hasSize;

*/

@Test

public void getUsers_2UsersExist_ReturnOK() throws Exception{

//data prep

addUsers();

//execute and verify

mvc.perform(get(basePath))

.andExpect(status().isOk())

.andExpect(content().contentType("application/json"))

.andExpect(jsonPath("$", hasSize(2)))

.andExpect(jsonPath("$[0].id").exists())

.andExpect(jsonPath("$[0].name").exists())

.andExpect(jsonPath("$[0].age").exists());

}

getUsers (unhappy path)

We also want to test the opposite scenario, when have no users. We expect an empty array, and an OK Http Status in our Response.

@Test

public void getUsers_NoUsers_ReturnOKEmptyArray() throws Exception{

// no data prep required

// execute

MockHttpServletResponse response = mvc.perform(

get(basePath).accept(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON))

.andReturn().getResponse();

// verify

assertThat(response.getStatus()).isEqualTo(HttpStatus.OK.value());

assertThat(response.getContentAsString()).isEqualTo("[]");

}

We cover each method under test with similar test cases.

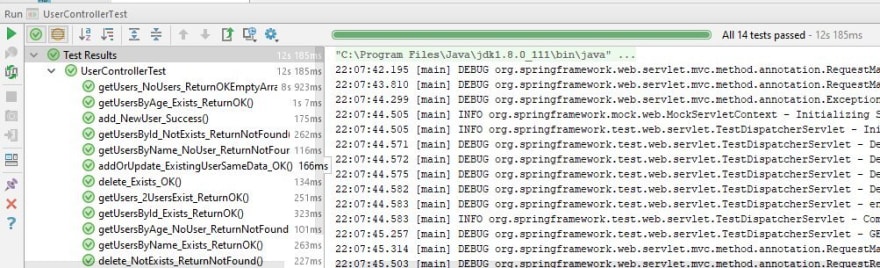

Execution Time for UserControllerTest

The execution time for the 14 test cases in UserControllerTest is 12 seconds. As you can see below most of the time is taken on the first test case, subsequent test cases benefit from caching, which makes them run in 100ms or so.

Integration Test for UserController

There are a few strategies for creating integration tests depending on how you define the scope of an integration test.

- If you use the annotation

@ExtendWith(SpringExtension.class), you can use use an application context. It is similar to the unit test, but you have the option of autowiring objects. - If you use the annotation

@SpringBootTestwithout parameters, or@SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.MOCK), *you can use an application context *. It is similar to the unit test, but you have the option of autowiring objects. This is a tricky approach to get right and is not advisable. - You can use the annotations

@SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.RANDOM_PORT)or@SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.DEFINED_PORT)to use a real HTTP server. In this case, you need to use aRestTemplateorTestRestTemplateto execute requests as it is an external test.

You can read the Guide to Testing Controllers in Spring Boot [^2] for a more in-depth look at these strategies. I will use strategy 3.

Writing the Integration Test with a real server

I named my integration test class as UserControllerIT. It has the same test cases as UserControllerTest.

The annotation @ExtendWith(SpringExtension.class) uses a JUnit 5 extension named SpringExtension, which initializes the Spring context. The annotation @SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.RANDOM_PORT) runs the server on a random port.

@ExtendWith(SpringExtension.class)

@SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = SpringBootTest.WebEnvironment.RANDOM_PORT)

public class UserControllerIT {

@Autowired

private TestRestTemplate restTemplate;

private String basePath = "/users";

private final User TEST_USER = new User(1, "Rob OLeary", 21);

private final User TEST_USER_2 = new User(2, "Angela Merkel", 20);

//test cases

}

Test Cases

In the tests cases, I use an instance of TestRestTemplate which was made with integration tests in mind. It has convenience methods getForEntity(URI url, Class<T> responseType) and postForEntity(URI url, Object request, Class responseType), which make it easy to execute GET and POST requests respectively, returning a response which converts the body to an object we define in the generic type <T>.

There are methods put(URI url, Object request) and delete(URI url) for executing PUT and DELETE requests, but they do return responses. If you want a response for assertions, you need to use one of the exchange(..) methods, and specify the HTTP method as one of the parameters.

For the test assertions, I use JSONAssert assertions. As an external test, it makes sense to me to test the response bodies as JSON, similar to an external consumer of the web service. You can use other assertion styles if you wish!

I will explain the same test cases as I did for UserControllerTest .

getUsers (happy path)

@Test

public void getUsers_2UsersExist_ReturnOK() throws Exception{

//data prep

postUsers();

// execute

ResponseEntity<String> response = restTemplate.getForEntity(basePath, String.class);

// verify

assertThat(response.getStatusCode()).isEqualTo(HttpStatus.OK);

String expected = "[{id:1,name:\"Rob OLeary\",age:21},{id:2,name:\"Angela Merkel\",age:20}]";

JSONAssert.assertEquals(expected, response.getBody(), JSONCompareMode.STRICT);

//cleanup

deleteUser( 1);

deleteUser( 2);

}

- Preparation: We write a helper method

postUsersto create Users to setup data. - Execution: We specify the type as String when using

getForEntity(URI url, Class<T> responseType), so we can useJSONAssertfor assertions on the response body . - Verify: Using

JSONAssert.assertEquals()is quite simple, we can compare it directly to an expected JSON String we write. You can declare the comparison mode as strict or lenient.

getUsers (unhappy path)

We also want to test the opposite scenario, when we have no users. We expect an empty array, and an OK Http Status in our Response.

@Test

public void getUsers_NoUsers_ReturnOKEmptyArray() throws Exception{

// no data prep required

// execute

ResponseEntity<String> response = restTemplate.getForEntity(basePath, String.class);

// verify

assertThat(response.getStatusCode()).isEqualTo(HttpStatus.OK);

JSONAssert.assertEquals("[]",response.getBody(),JSONCompareMode.STRICT);

}

Execution Time for UserControllerIT

The total execution time for the server initialisation and the 14 test cases is 39 seconds (first time), and around 28 seconds on subsequent runs. The equivalent unit test was 12 seconds in total!

Write a Test Suite

You can group tests together to run together as a test suite. You can make any kind of group you wish, I will write a test suite to run our user-related unit tests together.

Unfortunately, the test runner in JUnit 5 is not able to run your test suite (yet). You need to add a separate JUnit 4 test runner called JUnitPlatform to run your test suites in an IDE, which means you must include the vintage engine module of JUnit 5 also. Below is what test maven dependencies you should have.

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-test</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.junit.platform</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-platform-runner</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

The @selectPackages annotation specifies the packages your tests are contained in, JUnitPlatform will discover and run all tests in the package and its subpackages. By default, it will only include test classes whose names either begin with Test or end with Test or Tests.

import org.junit.platform.runner.JUnitPlatform;

import org.junit.platform.suite.api.SelectPackages;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform.class)

@SelectPackages("net.roboleary.user")

public class UserTestSuite { }

There are more configuration options for discovering and filtering tests available in the org.junit.platform.suite.api package.

You can run your test suite with Gradle, Maven, or the console launcher if you prefer.

Source Code

The code is available in a branch of the original github repository called 'with-tests'.

Final Words

I hope this gives a more nuanced explanation of testing a web application. I found it a bit disorientating in the beginning, I couldn't find tutorials with clear distinctions between the syntaxes and libraries that they were using, and clear objectives about their testing methodology.

When you have a web application with more layers, such as a persistence layer and service layer, you need to do a bit more with your tests, but it is just variation on what we have done already mostly. Discussing it with a complete application is the most illuminating way to learn about it.

Give a ❤ if you enjoyed the article or found it helpful. If you have questions or feedback, be sure to let me know! 🙂

Happy coding! 👩💻🙌

Two images were used to create the banner image, they were made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com.

References

- Why test POJOs? by Scott Shipp: Why test POJOs?

- Guide to Testing Controllers in Spring Boot: There are different ways to test your Controller (Web or API Layer) classes in Spring Boot, you can write unit tests and others are more useful for Integration Tests.

- Selective Unit Testing – Costs and Benefits: For certain types of code, unit testing works brilliantly, but for other types of code, writing unit tests consumes a huge amount of effort, doesn’t meaningfully aid design or reduce defects at all.

- Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration by Kent Dodds: Discusses testing strategy and advocates writing mostly integrations tests.

Top comments (1)