Background Context

It's been a bad month for sysadmins (Oct 2018), first youtube then github

GitHub Status@githubstatus

GitHub Status@githubstatus We are continuing work to repair a data storage system for GitHub.com. You may see inconsistent results during this process.04:12 AM - 22 Oct 2018

We are continuing work to repair a data storage system for GitHub.com. You may see inconsistent results during this process.04:12 AM - 22 Oct 2018

To start: #hugops to the folks at github for fixing their systems. It isn't easy to keep large-scale systems up and running (having been there myself)

Liquid error: internal

And apparently, while distributed data storage is used everywhere in the cloud, not many developers truly understand it...

So, what is distributed storage? Why does every major cloud provider use it? And, why and how do they fail?

What is Distributed Storage?

Distributed Storage, here, collectively refers to "Distributed data store" also called "Distributed databases" and "Distributed File System".

And is used in various forms from the NoSQL trend to most famously, AWS S3 storage.

The core concept is to form redundancy in the storage of data by splitting up data into multiple parts, and ensuring there are replicas across multiple physical servers (often in various storage capacities).

Data replica could either be stored as exact whole copies or compressed into multiple parts using Erasure Code

Because erasure code, encryption, parity bits, involves complex math to explain how they work and does not change much to the concepts in this article - other than compressing data. I would simply use the inaccurateerm "replicas", to save both of us the math lecture 😉

Regardless of the storage method used, this helps to ensure that there are X copies of data stored across Y servers. Where X <= Y. (For example, 3 replicas across 5 servers).

Ugh complex math, why do we do this?

In large scale systems, it is not a question of "if" a server will fail, but "when". After all, with the amount of hardware, it's pretty much a statistical fact.

And you really do not want such a large-scale system to go down whenever a single server sneezes.

This contrasts heavily against what used to be more commonplace - redundancy of drives on a single server (such as RAID 1), which protects data from hard-drive failure.

When done correctly, distributed storage systems, helps to make the system survive downtime, such as a complete server failure, an entire server rack being thrown away, or even the extreme of a nuclear explosion of a data center.

Or as xkcd puts it ...

Nuclear proof database? Wouldn't such a system be extremely slow?

Well, that depends... part of the reason why there are so many different distributed systems out there, is that all systems form some sort of compromise that favor one attribute over another. Examples include latency or ACID guarantees.

And one of the most common compromises for distributed systems is accepting the significant overheads involved in coordinating data across multiple servers. So when it comes to a single server node benchmarked against non distributed systems, they tend to lose out.

However, what they gain in return is horizontal scalability, such as the capability to span across a thousand nodes.

A common example that many developers might have experienced: Uploading a single large file to cloud storage can be somewhat slow. However, on the flip side they can upload as many files concurrently as their wallet will allow simultaneously because the load will be distributed across multiple servers.

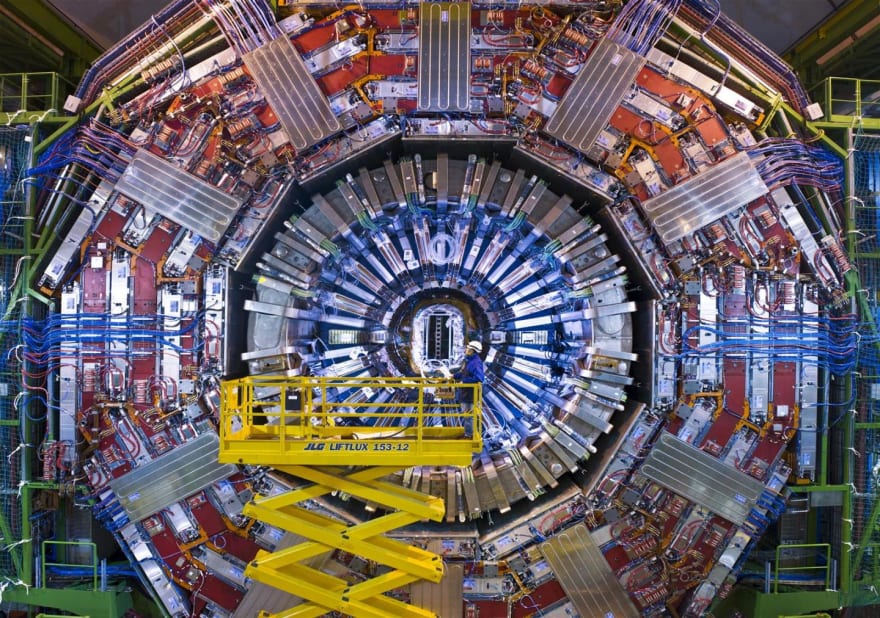

Or for CERN (you know, the giant Large Hadron Collider), it means 11,000 servers, with 200 PB of data, transmitting more then 200 Gigabits/s. With zero black holes found to date

So yes, a single server is "slow". For "fast" multi-server you have parallelism with replicas distributed among them.

Oh wow, cool. So how do these replicas get created in the first place?

Without going into how any one distributed system works, in general.

When a piece of data gets written to the system by a client program, its replicas are synchronously created into various other nodes in the process.

When a piece of data is read, the client either gets the data from one of the replica or from multiple replicas where a final result is decided by majority vote.

If any replica is found corrupted or missing due to a crash, its replica is removed from the system. And a new replica is created and placed onto another server, if available. This either happens on read or through a background checking process.

Deciding on what data is valid or corrupted and where each replica data should be, it is generally decided by a "master node" or via a "majority vote". And sometimes for choosing where replicas goes "randomly".

One of the most important recurring thing to take note, however, is the system requirement for majority vote for many operations, among all redundancies for the system to work.

With so many redundancies in place, how does it still fail?

First off... that depends on your definition of failure...

| System State | Description |

|---|---|

| All 💚 | Every node and replica is working. Yay! |

| Majority of replicas are 💚 | Everything is fine. Replicas may be down, but as long as we have the majority, users will not notice a thing as long as we replace those downed replicas in time... |

| Majority of replicas are 🔴 | Houston, we have a problem. Depending on the system design, it either goes into read-only mode, a hard failure state, or just continue on as per normal (rare) with the rest of the nodes, and suffer from split brain. |

| All 🔴 | Everything is down. Oops. Hopefully we can recover the cluster or restore those backups. They do exist, right? 😭 |

One of the big benefits of a distributed system - is that in many cases when a single node or replica fails, behind the scenes there will be a system reliability engineer (or sysadmin) who will be replacing the affected servers without any users noticing.

Which is probably one of the most overlooked and thankless aspects of the work involved. No one is aware of what happens. On record, this has already happened twice within Uilicious this year, and for infrastructure the size of Google and Amazon, I'm certain it would be a daily occurrence. So #hugops

Another thing to take note is the definition of failure from a business perspective. Permanently losing all of your customer data is a lot worse then entering, let's say, read-only mode or even crashing the system.

Particularly for github, if users have yet to push their commits - they are well aware they need to keep their local copy of the data for later uploads. However, if they have already uploaded, they might delete their local copy to clear up space for their <1TB SSD storage laptops.

Hence, many such systems are designed to shut down or enter read-only first, where long, manual restoration would be needed instead, to ensure data safety. Which is by design a "partial failure".

And finally... Murphy's law... means that sometimes multiple nodes or segments of your network infrastructure will fail. You will face situations where the majority vote is lost.

How is a redundancy fixed then?

With cloud systems, this typically means replacing a replica with a new instance.

However, depending on one's network infrastructure and data set size, time is a major obstacle.

For example to replace a single 8TB node with a gigabit connection (or 800 megabits/second effectively), one would take approximately 22.2 hours, or 1 whole day rounded up. And that's assuming optimal transfer rates which would saturate the system. To keep the system up and running without noticeable downtime, we may halve the transfer rate, doubling the time required to 2 whole days.

Naturally, more complex factors will come into play, such as 10-gigabit connections, or hard-drive speed.

However, the main point stays the same, replacing a damaged replica in a "large" storage node is hardly instantaneous.

This is also why you will see tweets with ETA on how long it will take for data to get synced up in a cluster

And for the record, considering that they are probably running a multi Peta Byte cluster, getting data synced up in a day is "fast"

And it's sometimes during these long 48 hours moments where things gets tense for the sysadmin. With a 3 replica configuration, there would be no room for mistakes if the majority of 2 healthy nodes is to be maintained. For a 5 replica configuration, there would be breathing room of 1.

And when majority vote is lost, one of three things would occur:

- Split brain : where you end up with a confused cluster

- Read-only mode : to prevent the system from having 2 different datasets (and hence a split brain)

- Hard system failure : Some systems prefer inducing a hard failure, rather than causing a split brain.

Ugh, my head hurts? What is the split brain problem?

A split brain starts to occur when your cluster starts splitting into 2 segments. Your system would start seeing two different versions of the same data as the cluster goes out of sync.

This happens most commonly when a network failure causes half of the cluster to be isolated from the other half.

What happens subsequently if data change were to occur, is that half of the system would be updated with the other half outdated.

This is "alright" until the other half comes back online. And the data might be out of sync or even changed due to usage with the other half of the cluster.

Both halves would start claiming they are the "real" data and vote against the "other half". And as with any voting system that is stuck in a gridlock, no work gets done.

This can happen even with an odd number of replicas. For example, if one replica has a critical failure and decides to "not vote"

Ok so how do we prevent this in the first place?

Fortunately, most distributed systems, when configured properly, is designed to prevent split brain from happening in the first place. They typically comes in 3 forms.

A master node which gets to make all final decisions (this however may cause a single point of failure of a master node going down. Some systems fallback to voting a new master node if it occurs).

Hard system failure to prevent such split brain. Until the cluster is all synced back up properly; This ensures that no "outdated" data is shown.

Locking the system in readonly; The most common sign of this would be when certain nodes show outdated data, in read-only mode.

The latter being the most common for most distributed systems, also seen in the recent github downtime

GitHub Status@githubstatus

GitHub Status@githubstatus We continue work to repair a data storage system for GitHub.com. You may see inconsistent results during this process.02:01 AM - 22 Oct 2018

We continue work to repair a data storage system for GitHub.com. You may see inconsistent results during this process.02:01 AM - 22 Oct 2018

A notable exception would be distributed cache systems such as hazelcast : which would take the approach of the data with the "latest" timestamp wins in resolving split brain problems.

This maybe "alright" in a caching use case, and is intentionally so, but it might be a big problem for more persistent storage system as it will lead to data being discarded. In many cases this situation would need some context specific decision to be made by either the programmer or the sysadmin to resolve.

That's a lot to take in - so how can I use one of these then?

Well you probably already are

These days most entry level AWS, or GCP instances use some form of "block storage" backend for their hard-drives, which is a distributed storage system.

More famously would be Object Storage such as S3 itself and pretty much any cloud storage. Even for dedicated servers, most backups system such as the ones provided by linode and digital ocean, use some form of distributed storage.

Beyond cloud services, there are many open source deployments that use distributed storage. Pretty much all NoSQL database, even kubernetes itself because it comes deployed with ETCD a distributed key-value storage.

Subsequently for notable specific applications, there is Cockroach DB (SQL), GlusterFS (File storage), Elasticsearch (NoSQL), Hadoop (Big data). Even mysql can be deployed in such a setup, known as group replication. Or alternatively through galera.

The ability to use such distributed systems and not think about it, is ultimately what you pay for on the "cloud-tax" - for someone behind the scene solving these problems for you.

So should I be angry when github or a cloud provider is down?

Be cool and #hugops - give them time, they are probably on it to the best of their abilities. Even the best of us can make the same mistakes.

Special thanks: to @feliciahsieh for helping proofread and fix all my awful commas and grammar.

About Uilicious

Uilicious is a simple and robust solution for automating UI testing for web applications. Signing up for our free trial and writing test scripts to validate your distributed system, can be as easy as the script below.

Or alternatively, test such as these ...

UPDATE: This is now turned into a series with a part 2 expanding on distributed storage systems.

Top comments (5)

For amazon 2017 case it was human error, and im quite sure since then they probably added more code in to prevent the exact same mistake from happening.

However to answer that question in more general terms ...

Typically for half a cluster on that scale to fail. Its most commonly either from

Its rarely a single server itself

Most of these 1K+ server systems, can actually handle gradual node by node, or zone by zone failure really well (about ~10% failure), especially with an active team monitoring and adjusting it, and sufficient time given in between. So for example if lets say I have 2 million servers (i wish) and for some reason 0.2 million in korea has been destroyed. I could reconfigure the remaining 1.8 million to reject the failed 0.2 million, and ensure they have sufficient replica among themselves. And the rest of the world would not notice the system down (in their fallout shelter).

Side note for clusters at this scale, majority vote may not be just 50%+1, and are typically configured to be at 60%-80% threshold.

However all of this works assuming our networking (ie: internet) is working as designed. And that the above concepts is implemented in code by design (sometimes its simply bugs 😶)

Depending on where you live - your internet connection to certain parts of the world maybe dependent on only a handful of fiber optical cables, or even one. As ISP may preconfigure certain ip addresses to a fixed route.

(Above is World map of major fiber optical cables for reference)

And all it takes from there is one of these fiber choke points, to either go down (which infamously happened for the entire country of Armenia), or to be misconfigured, either by the ISP or the data center router (which could effectively be in a single line, of configuration or code error).

The core backbone of the internet is very heavily dependent on being properly configured by every trusted party involved with it. And sometimes - things happen like google accidentally disconnecting japan

Hence when such network failure happens - the cluster could then be all of sudden split into two, both side failing one another to protect their data. Half being on either side of the broken link.

Even then, once the connection is restored. And sometimes especially for misconfiguration errors it could only be for a few minutes. To prevent data corruption, the two halves of the cluster would very commonly scan and verify each replica, by comparing every one of them. A process which could take hours.

Cheers, hopefully this helps highlight two of the many possible reasons.

Assuming its not handed over and covered up by SERN 😂

Loved the article, thanks!

It's not just funny but also extremely accurate. Shame I can't give more than one heart to this.

A comment like this alone is worth multiple ❤️s

=)