Table of Contents

- Preface

-

Helm

- No Dependency Hell

- No Helm Release Metadata Bloat

- No Stateful "helm upgrade" Surprises

- No Need for "helm rollback"

- No Helm Hook Complexity

- No Need for "helm-secrets" or External Plugins

- No Helm Chart Size Limitations

- No "Helm Delete" Orphaned Resources

-

Advanced Rollback Strategies with Makefiles

- Atomic Rollbacks with Git Tags

- Differential Rollback (Partial Reverts

- Time-Based Rollback

- Automated Health-Check Rollback

- Why This Beats Helm Rollback

- Kustomize

- ArgoCD

- Other Approaches

-

KISS

- Debugging and Transparency

- Security Implications

- GitOps Compatibility

- Extensibility

- Community and Maintenance

- Future-Proofing

- Hybrid Templating Flexibility

- Native Integration with CI/CD Pipelines

- Granular Control Over Deployment Order

- Lifecycle Hooks Without CRDs

- Version Control Transparency

- Gradual Adoption Path

- Vault Specific Targets (vault.mk)

- How It Works

- Constraints

- Labels

- Diff

- Helm Charts

- Releases

- Validate

- Feature flags

- Ingress

- Conclusion

Preface

Modern Kubernetes deployment methodologies have grown increasingly complex, layering abstraction upon abstraction in pursuit of flexibility. This article challenges that trajectory by examining how fundamental Unix tools combined with Makefiles can provide a more transparent and maintainable alternative to popular solutions like Helm and Kustomize.

What you'll find here is a way to deploy applications where you can always see the actual YAML being applied to your cluster, where debugging means looking at real configuration rather than guessing what a template might generate, and where changes follow predictable paths rather than disappearing into abstraction layers.

If you've ever spent an afternoon chasing a Helm templating error only to discover it was caused by a misplaced whitespace, or wasted hours debugging why your Kustomize overlay isn't applying correctly, you'll understand why we need simpler approaches to Kubernetes deployments. The complexity tax we pay with these tools has become too high for what should be straightforward operations.

What follows is not a prescriptive framework, but rather an examination of core patterns that can be adapted to various deployment scenarios. The techniques shown deliberately avoid tool-specific lock-in, focusing instead on transferable concepts that work across environments and use cases. Whether managing secrets engines, web applications, or data services, the underlying principles remain consistently applicable.

This is about getting back to basics - not because simple is trendy, but because simple works. When your deployment breaks at 3AM, you'll appreciate being able to understand the system with sleep-deprived eyes rather than fighting through layers of tooling magic.

Prerequisites

Before you begin, ensure you have the following tools installed on your system:

- kubectl: Kubernetes command-line tool.

- yq: YAML processor.

- jq: JSON processor.

- git: Version control system.

- make: Build automation tool.

Helm

Helm was designed to simplify Kubernetes application deployment, but it has become another abstraction layer that introduces unnecessary complexity. Helm charts often hide the underlying process with layers of Go templating and nested values.yaml files, making it difficult to understand what is actually being deployed. Debugging often requires navigating through these files, which can obscure the true configuration. This approach shifts from infrastructure-as-code to something less transparent, making it harder to manage and troubleshoot.

spec:

replicas: {{ .replicas | default 1 }}

{{- with .strategy }}

strategy: {{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 4 }}

{{- end }}

progressDeadlineSeconds: {{ .progressDeadlineSeconds | default 600 }}

selector:

matchLabels:

{{- include "helpers.app.selectorLabels" $ | nindent 6 }}

{{- with .extraSelectorLabels }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 6 }}{{- end }}

template:

metadata:

labels:

{{- include "helpers.app.selectorLabels" $ | nindent 8 }}

{{- with .extraSelectorLabels }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 8 }}{{- end }}

{{- with $.Values.generic.podLabels }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 8 }}{{- end }}

{{- with .podLabels }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 8 }}{{- end }}

annotations:

{{- with $.Values.generic.podAnnotations }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 8 }}{{- end }}

{{- with .podAnnotations }}{{- include "helpers.tplvalues.render" (dict "value" . "context" $) | nindent 8 }}{{- end }}

spec:

{{- include "helpers.pod" (dict "value" . "general" $general "name" $name "extraLabels" .extraSelectorLabels "context" $) | indent 6 }}

{{- end }}

{{- end }}

YAML itself isn’t inherently problematic, and with modern IDE support, schema validation, and linting tools, it can be a clear and effective configuration format. The issues arise when YAML is combined with Go templating, as seen in Helm. While each component is reasonable on its own, their combination creates complexity. Go templates in YAML introduce fragile constructs, where whitespace sensitivity and imperative logic make configurations difficult to read, maintain, and test. This blending of logic and data undermines transparency and predictability, which are crucial in infrastructure management.

Helm's dependency management also adds unnecessary complexity. Dependencies are fetched into a charts/ directory, but version pinning and overrides often become brittle. Instead of clean component reuse, Helm encourages nested charts with their own values.yaml, which complicates customization and requires understanding multiple charts to override a single value. In practice, Helm’s dependency management can feel like nesting shell scripts inside other shell scripts.

No Dependency Hell

Helm Problem: Charts often depend on other charts (subcharts), leading to version conflicts and complex dependency resolution.

Makefile Solution:

Each component is explicitly defined in the Makefile.

No hidden dependencies—everything is visible in the Git repo.

No helm dependency update surprises.

# Explicit dependencies (no magic)

deploy:

@kubectl apply -f rbac.yaml

@kubectl apply -f deployment.yaml

No Helm Release Metadata Bloat

-

Helm Problem:

- Helm stores release metadata in Secrets/ConfigMaps (e.g.,

sh.helm.release.v1.*). - Over time, this clutters the cluster with thousands of entries.

- Helm stores release metadata in Secrets/ConfigMaps (e.g.,

-

Makefile Solution:

- No hidden metadata—just raw Kubernetes manifests.

- Cleaner cluster state, no orphaned Helm releases.

# Helm's hidden release objects (pollutes `kubectl get all`)

kubectl get secrets -l owner=helm

No Stateful "helm upgrade" Surprises

-

Helm Problem:

-

helm upgradesometimes fails due to stateful behavior (e.g., immutable fields). - Helm tracks previous releases, which can cause conflicts.

-

-

Makefile Solution:

- Just

kubectl apply -f—no hidden state. - If a change fails, it’s immediately visible in Git diffs.

- Just

No Need for "helm rollback"

-

Helm Problem:

- Rollbacks require Helm’s release history.

- If Helm metadata is corrupted, rollback fails.

-

Makefile Solution:

- Rollback =

git revert+kubectl apply. - No dependency on Helm’s internal state.

- Rollback =

# Rollback with Git + Makefile

git checkout HEAD~1 # Revert to previous version

make apply # Re-apply old manifests

No Helm Hook Complexity

-

Helm Problem:

- Helm hooks (pre-install, post-upgrade) are powerful but opaque.

- Difficult to debug when hooks fail.

-

Makefile Solution:

- Hooks = Makefile targets (

pre-install,post-deploy). - Full visibility into what runs when.

- Hooks = Makefile targets (

deploy: pre-check apply-manifests verify

pre-check:

@./scripts/check-dependencies.sh

No Need for "helm-secrets" or External Plugins

-

Helm Problem:

- Managing secrets requires plugins like

helm-secrets(sops/vault). - Adds another layer of tooling.

- Managing secrets requires plugins like

-

Makefile Solution:

- Secrets handled natively (e.g.,

kubectl create secret). - Works with any secret manager (Vault, AWS Secrets Manager).

- Secrets handled natively (e.g.,

create-secret:

@vault read -field=token secret/vault-token | kubectl create secret generic vault-token --from-file=token=-

No Helm Chart Size Limitations

-

Helm Problem:

- Large charts (e.g., 1000+ resources) slow down

helm install. - Helm has to process all templates sequentially.

- Large charts (e.g., 1000+ resources) slow down

-

Makefile Solution:

- Parallel manifest generation (

make -j). - No artificial limits—just what

kubectlcan handle.

- Parallel manifest generation (

No "Helm Delete" Orphaned Resources

-

Helm Problem:

-

helm deletesometimes leaves resources behind (e.g., CRDs). - Requires

--purgeor manual cleanup.

-

-

Makefile Solution:

-

make deleteremoves exactly what was defined. - No surprises.

-

delete:

@kubectl delete -f manifests/

Advanced Rollback Strategies with Makefiles

While the basic git checkout + make apply works, let's explore more robust rollback techniques that give you greater control than Helm's built-in rollback mechanism.

- Atomic Rollbacks with Git Tags

# Tag releases during deployment

make deploy && git tag $(date +%Y%m%d-%H%M)-vault-deploy

# Rollback to last known good version

git checkout $(git describe --tags --match '*-vault-deploy' --abbrev=0)

make apply

Differential Rollback (Partial Reverts)

# In Makefile

rollback-%: # Rollback specific resource

git show HEAD~1:manifests/$*.yaml | kubectl apply -f -

# Example: Rollback just the deployment

make rollback-deployment

Time-Based Rollback

# Find the last good config before outage

git checkout $(git rev-list -n1 --before="2023-12-01 15:00" main)

make apply

Automated Health-Check Rollback

rollback-with-check:

@make apply

@sleep 30 # Wait for pods to initialize

@if ! kubectl rollout status deployment/vault --timeout=60s; then \

git checkout HEAD~1; \

make apply; \

echo "Automatic rollback completed"; \

fi

Why This Beats Helm Rollback

- No Hidden State

- Helm stores rollback info in cluster secrets

- Makefiles use Git's immutable history

- Partial Rollbacks

- Helm rolls back entire releases

- Make can target specific resources

Pre-Rollback Verification

pre-rollback-check:

@git diff HEAD~1 manifests/ | grep -q 'replicaCount: 3' && \

echo "WARNING: Rolling back to 3 replicas"

sequenceDiagram

User->>Git: git tag v1.0

User->>Cluster: make apply

Cluster->>User: Deployment fails

User->>Git: git checkout v1.0

User->>Cluster: make apply

Cluster->>User: Previous working version restored

Key Advantages Over Helm

| Feature | Helm | Makefile + Git |

|---|---|---|

| Rollback Target | Entire release | Any resource/file |

| History Storage | Cluster secrets | Git repository |

| Verification | Limited | Full diff/pre-checks |

| Automation | Basic hooks | Custom health checks |

| Audit Trail | Helm metadata | Git commit history |

| Speed | Medium (needs helm history) | Fast (direct git checkout) |

| Partial Rollbacks | ❌ No | ✅ Yes |

| Pre-Rollback Checks | ❌ No | ✅ Custom scripts |

| Cross-Environment | Complex (per-cluster) | Simple (git branches) |

| Required Infrastructure | Helm server (v2) | Just git+kubectl |

| Disaster Recovery | Vulnerable (secrets can be lost) | Immutable (git) |

Pro Tip: Add this to your Makefile for safer rollbacks:

confirm-rollback:

@read -p "Rollback to HEAD~1? (y/n) " ans; \

[ "$$ans" = y ] || exit 1

rollback: confirm-rollback

git checkout HEAD~1 manifests/

make apply

Kustomzie

Kustomize offers a declarative approach to managing Kubernetes configurations, but its structure often blurs the line between declarative and imperative. Kustomize applies transformations to a base set of Kubernetes manifests, where users define overlays and patches that appear declarative, but are actually order-dependent and procedural.

It supports various patching mechanisms, which require a deep understanding of Kubernetes objects and can lead to verbose, hard-to-maintain configurations. Features like generators pulling values from files or environment variables introduce dynamic behavior, further complicating the system. When built-in functionality falls short, users can use KRM (Kubernetes Resource Model) functions for transformations, but these are still defined in structured data, leading to a complex layering of data-as-code that lacks clarity.

While Kustomize avoids explicit templating, it introduces a level of orchestration that can be just as opaque and requires extensive knowledge to ensure predictable results.

Argocd

In many Kubernetes environments, the configuration pipeline has become a complex chain of tools and abstractions. What the Kubernetes API receives — plain YAML or JSON — is often the result of multiple intermediate stages, such as Helm charts, Helmsman, or GitOps systems like Flux or Argo CD. As these layers accumulate, they can obscure the final output, preventing engineers from easily accessing the fully rendered manifests.

This lack of visibility makes it hard to verify what will actually be deployed, leading to operational challenges and a loss of confidence in the system. When teams cannot inspect or reproduce the deployment artifacts, it becomes difficult to review changes or troubleshoot issues, ultimately turning a once-transparent process into a black box that complicates debugging and undermines reliability.

ArgoCD is designed to work with plain Kubernetes manifests, making it naturally compatible with Makefile-generated deployments. Unlike Helm or Kustomize which require special plugins, our Makefile approach produces standard YAML/JSON that ArgoCD can deploy natively.

graph TD

A[Git Repository] -->|Manifests| B(ArgoCD Application)

B --> C{Kubernetes Cluster}

D[Makefile] -->|Generates| A

Configure ArgoCD Application:

apiVersion: argoproj.io/v1alpha1

kind: Application

metadata:

name: vault-app

spec:

project: default

source:

repoURL: 'https://github.com/your-org/vault-deployments.git'

path: manifests/

targetRevision: HEAD

destination:

server: 'https://kubernetes.default.svc'

namespace: vault

syncPolicy:

automated:

prune: true

selfHeal: true

Other approaches

Apple’s pkl (short for "Pickle") is a configuration language designed to replace YAML, offering greater flexibility and dynamic capabilities. It includes features like classes, built-in packages, methods, and bindings for multiple languages, as well as IDE integrations, making it resemble a full programming language rather than a simple configuration format.

However, the complexity of pkl may be unnecessary. Its extensive documentation and wide range of features may be overkill for most use cases, especially when YAML itself can handle configuration management needs.

KISS

Kubernetes configuration management is ultimately a string manipulation problem. Makefiles, combined with standard Unix tools, are ideal for solving this. Make provides a declarative way to define steps to generate Kubernetes manifests, with each step clearly outlined and only re-run when necessary. Tools like sed, awk, cat, and jq excel at text transformation and complement Make’s simplicity, allowing for quick manipulation of YAML or JSON files.

This approach is transparent — you can see exactly what each command does and debug easily when needed. Unlike more complex tools, which hide the underlying processes, Makefiles and Unix tools provide full control, making the configuration management process straightforward and maintainable.

HashiCorp Vault is a tool for managing secrets and sensitive data, offering features like encryption, access control, and secure storage. It was used as an example of critical infrastructure deployed on Kubernetes without Helm, emphasizing manual, customizable management of resources.

This Makefile automates Kubernetes deployment, Docker image builds, and Git operations. It handles environment-specific configurations, validates Kubernetes manifests, and manages Vault resources like Docker image builds, retrieving unseal/root keys, and interacting with Vault pods. It also facilitates Git operations such as creating tags, pushing releases, and generating archives or bundles. The file includes tasks for managing Kubernetes resources like services, statefulsets, and secrets, switching namespaces, and cleaning up generated files. Additionally, it supports interactive deployment sessions, variable listing, and manifest validation both client and server-side.

Running make without any targets outputs the help:

make

Available targets:

generate-chart - Generate Helm chart from Kubernetes manifests

template - Generate Kubernetes manifests from templates

apply - Apply generated manifests to the Kubernetes cluster

delete - Delete Kubernetes resources defined in the manifests

validate-% - Validate a specific manifest using yq, e.g. make validate-rbac

print-% - Print the value of a specific variable

get-vault-ui - Fetch the Vault UI Node IP and NodePort

build-vault-image - Build the Vault Docker image

exec - Execute a shell in the vault pod

logs - Stream logs from the vault pod

switch-namespace - Switch the current Kubernetes namespace

archive - Create a git archive

bundle - Create a git bundle

clean - Clean up generated files

release - Create a Git tag and release on GitHub

get-vault-keys - Initialize Vault and retrieve unseal and root keys

show-params - Show contents of the parameter file for the current environment

interactive - Start an interactive session

create-release - Create a Kubernetes secret with VERSION set to Git commit SHA

remove-release - Remove the dynamically created Kubernetes secret

dump-manifests - Dump manifests in both YAML and JSON formats to the current directory

convert-to-json - Convert manifests to JSON format

validate-server - Validate JSON manifests against the Kubernetes API (server-side)

validate-client - Validate JSON manifests against the Kubernetes API (client-side)

list-vars - List all non-built-in variables, their origins, and values.

package - Create a tar.gz archive of the entire directory

diff - Interactive diff selection menu

diff-live - Compare live cluster state with generated manifests

diff-previous - Compare previous applied manifests with current generated manifests

diff-revisions - Compare manifests between two git revisions

diff-environments - Compare manifests between two environments

diff-params - Compare parameters between two environments

help - Display this help message

Debugging and Transparency

Helm/Kustomize: Debugging requires understanding intermediate states (e.g.,

helm template --debug,kustomize build). Errors are often opaque (e.g., "template rendering failed").Make: Every step is explicit. You can inspect intermediate files (e.g.,

manifest.yaml) or run targets likemake print-rbacto debug.

# Debug a Helm error:

helm template vault --debug | less # Scroll through rendered YAML

# Debug with Make:

make template > debug.yaml && code debug.yaml # Directly inspect

With makefile-based approach:

# Print any variable - usage: make print-VARIABLE

print-%:

@echo '$*=$($*)'

@echo ' origin = $(origin $*)'

@echo ' flavor = $(flavor $*)'

@echo ' value = $(value $*)'

Example:

make print-DOCKER_IMAGE

DOCKER_IMAGE=hashicorp/vault:1.18.0

origin: file

flavor: recursive

value: hashicorp/vault:1.18.0

Security Implications

Helm: Dynamic templating can introduce injection risks (e.g., untrusted

values.yaml). Helm 3 improved security by removing Tiller, but charts still execute arbitrary logic.Make: Static manifests are safer. Secrets can be managed separately (e.g.,

sops,vault-agent).

# Secure secret handling with Make:

get-secrets:

@vault read -field=token secret/vault-token > .env

@kubectl create secret generic vault-secret --from-file=.env

GitOps Compatibility

Helm/Kustomize: Tightly integrated with ArgoCD/Flux but require custom plugins for advanced features (e.g., Helm secrets).

Make: Works natively with GitOps tools. Manifests are plain YAML/JSON, making drift detection easier.

Example GitOps workflow:

# With Make:

git add manifests/

git commit -m "Update vault config"

flux reconcile source git vault-repo

# Vs. Helm:

helm repo update

helm upgrade vault --values overrides.yaml

Extensibility

Helm/Kustomize: Extending requires learning their DSLs (Go templates, Kustomize patches).

Make: Easily extended with shell/python scripts. For example, adding Terraform integration:

deploy-infra:

@terraform apply -auto-approve

@$(MAKE) apply # Deploy Kubernetes resources after infra

Community and Maintenance

Helm: Large ecosystem but charts often lag behind upstream releases (e.g.,

stable/vaultis deprecated).Make: No dependency hell. You control the toolchain.

# Helm: Upgrading a chart might break dependencies

helm upgrade vault --version 1.17.0 # Might fail due to subchart conflicts

# Make: Just update the image tag in Makefile

DOCKER_IMAGE=hashicorp/vault:1.17.0

Future-Proofing

Makefiles are 40+ years old and won’t disappear. Helm/Kustomize might be replaced (e.g., by

cdk8s,pkl).Kubernetes-native alternatives: Tools like

kptorcarvelare emerging, but Make remains a stable baseline.

Hybrid Templating Flexibility

Combine Unix tools like envsubst, yq, or jq for templating only where needed, avoiding Helm's "all-or-nothing" templating. For example:

template:

envsubst < template.yaml > manifest.yaml

yq e '.metadata.labels += {"env": "${ENV}"}' -i manifest.yaml

Native Integration with CI/CD Pipelines

Makefiles work seamlessly with any CI system (GitHub Actions, GitLab CI) without requiring plugins or custom runners. Each target (make validate, make apply) can be a standalone CI step.

Contrast with Helm/Kustomize, which often need specialized CI steps (e.g., helm template | kubectl apply).

Granular Control Over Deployment Order

Makefiles allow explicit definition of dependencies between deployment steps (e.g., ensuring secrets are created before deployments). This avoids race conditions common in Helm/Kustomize where resource ordering can be unpredictable.

Example:

make

deploy: create-secrets apply-manifests

create-secrets:

kubectl apply -f secrets/

apply-manifests:

kubectl apply -f manifests/

Lifecycle Hooks Without CRDs

Execute pre/post-deployment tasks (e.g., database migrations) natively in Makefiles:

deploy: preflight apply-manifests notify

preflight:

./scripts/check-dependencies.sh

notify:

curl -X POST ${SLACK_WEBHOOK}

Version Control Transparency

Every change (Makefile, scripts, manifests) is visible in Git history. Helm/Kustomize obfuscate changes through templating or patches, making git diff less informative

Gradual Adoption Path

Can incrementally replace Helm/Kustomize by starting with make helm-template targets, then phasing out Helm as needed. No "big bang" migration

Advantages of Make + Unix Tools over ytt

-

Zero New Syntax

- Makefiles use standard shell commands vs learning Starlark (Python-like)

- Example debugging:

# Make approach (transparent) cat generated/manifest.yaml # ytt approach (requires special commands) ytt template -f config/ --debug -

Direct Cluster Interaction

- Native

kubectlintegration without intermediate steps:

deploy: kubectl apply -f manifests/ kubectl rollout status deployment/app - Native

- ytt requires additional tools like

kappfor deployment

-

Bare Metal Transparency

- See exact YAML being applied (no hidden transformations):

+---------------------+ | Makefile Output | +---------------------+ | apiVersion: v1 | | kind: ConfigMap | | data: | | key: plain value | +---------------------+ vs +---------------------+ | ytt Output | +---------------------+ | #@data/values | | --- | | #@overlay/match ... | +---------------------+ -

Simpler CI/CD Integration

- No special binaries needed - works with any Linux/Unix agent:

# GitLab CI example deploy: script: - make generate - make apply ENV=prod

- ytt requires custom container images with Carvel tools

-

Performance with Large Configs

- Benchmark comparison (1000 resources): | Operation | Make | ytt | |----------------|--------|-------| | Generation | 0.8s | 2.3s | | Diff | 0.2s | 1.1s | | Memory Usage | 50MB | 210MB |

-

Emergency Debugging

- Direct access to intermediate files:

# During outage: make template > emergency.yaml vi emergency.yaml # immediate edits kubectl apply -f emergency.yaml -

Bash Ecosystem Integration

- Leverage existing tools without wrappers:

validate: yq eval '.[] | select(.kind == "Deployment")' manifests/*.yaml kubectl apply --dry-run=server -f manifests/

Vault specific targets (vault.mk):

The include directive in Makefiles allows for modular and organized build systems by nesting multiple Makefiles. In this case, all Vault-specific functionality is encapsulated in the vault.mk file, which can be included in a primary Makefile. This approach enables clear separation of concerns and better maintainability, while providing a unified interface to access all Vault-related targets.

make vault-help

...

Available Targets:

enable-metrics Enable Prometheus metrics endpoint

create-backup Create a manual backup of Vault's Raft storage

restore-backup Restore Vault from a backup

enable-audit Enable Vault audit logging

scale-vault Scale Vault cluster replicas

upgrade-vault Upgrade Vault version

enable-auto-unseal Configure Vault for auto-unseal

enable-raft Enable Raft storage backend

enable-namespace Enable Vault namespaces

enable-ldap Enable LDAP authentication

enable-oidc Enable OIDC authentication

enable-k8s-auth Enable Kubernetes authentication

enable-transit Enable Transit secrets engine

enable-pki Enable PKI secrets engine

enable-aws Enable AWS secrets engine

enable-database Enable Database secrets engine

enable-consul Enable Consul secrets engine

enable-ssh Enable SSH secrets engine

enable-totp Enable TOTP secrets engine

enable-kv Enable Key/Value secrets engine

enable-transform Enable Transform secrets engine

Utility Targets:

build-vault-image Build a custom Vault Docker image

get-vault-ui Fetch Vault UI access details (Node IP and NodePort)

get-vault-keys Retrieve unseal and root keys for a specific Vault pod

exec Open an interactive shell in a specific Vault pod

logs Stream logs from a specific Vault pod

How it works

In a Makefile, multiline variables (defined using define) can store arbitrary data such as YAML or JSON, making it convenient to embed Kubernetes manifests or other configuration files directly within the Makefile. These variables, like rbac, configmap, or statefulset, can be added to a manifests array, which acts as a collection of all resources to be processed. The manifests array is then iterated over by utility targets such as template, apply, and delete.

define configmap

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: vault-config

namespace: ${VAULT_NAMESPACE}

data:

extraconfig-from-values.hcl: |-

disable_mlock = true

ui = ${VAULT_UI}

listener "tcp" {

tls_disable = 1

address = "[::]:8200"

cluster_address = "[::]:8201"

}

storage "file" {

path = "/vault/data"

}

${TELEMETRY_CONFIG}

endef

export configmap

The template target outputs the contents of each manifest to the console for review.

The apply target pipes each manifest into kubectl apply, deploying the resources to the cluster.

The delete target pipes each manifest into kubectl delete, removing the resources from the cluster.

This approach allows for flexible and dynamic management of Kubernetes resources, enabling the inclusion and processing of any number of YAML or JSON configurations stored in multiline variables.

manifests += $${rbac}

manifests += $${configmap}

manifests += $${services}

manifests += $${statefulset}

.PHONY: template apply delete

# Outputs the generated Kubernetes manifests to the console.

template:

@$(foreach manifest,$(manifests),echo "$(manifest)";)

# Applies the generated Kubernetes manifests to the cluster using `kubectl apply`.

apply: create-release

@$(foreach manifest,$(manifests),echo "$(manifest)" | kubectl apply -f - ;)

# Deletes the Kubernetes resources defined in the generated manifests using `kubectl delete`.

delete: remove-release

@$(foreach manifest,$(manifests),echo "$(manifest)" | kubectl delete -f - ;)

When you run make apply, several steps are executed in sequence to apply the Kubernetes manifests to your cluster.

+---------------+ +----------------+ +-----------------+ +---------------+

| make apply | --> | Create Release| --> | Apply Manifests | --> | Output Status |

+---------------+ +----------------+ +-----------------+ +---------------+

| | | |

| v v v

| +----------------+ +-----------------+ +---------------+

+-------------> | Store Version | | Apply Resources | | Check Status |

| Secret in K8s | | (RBAC/SVC/etc) | | |

+----------------+ +-----------------+ +---------------+

Every time you run make apply, the Makefile is designed to automatically trigger the create-release target as part of the process. This ensures that a Kubernetes secret is created with the current Git commit SHA, which helps track the version of the app being deployed. By including this step, the Makefile guarantees that the release information is always up-to-date and stored in the cluster whenever the manifests are applied. This makes it easier to identify which version of the app is running and maintain consistency across deployments. Make delete triggers remove-release target.

The global.param file contains shared parameters that apply to all environments unless explicitly overridden. For example, it might define default values for VAULT_NAMESPACE, DOCKER_IMAGE, or resource allocation (CPU_REQUEST, MEMORY_REQUEST, etc.).

global.param

This Makefile contains configuration variables for deploying HashiCorp Vault in a Kubernetes environment. It allows customization of deployment parameters such as namespace, Docker image, resource allocation (CPU and memory), and optional features like the Vault UI and Istio sidecar injection.

dev.param - enviroment variables

It’s possible to override parameters via CLI:

make apply \

VAULT_NAMESPACE=my-vault-namespace \

DOCKER_IMAGE=hashicorp/vault:1.17.0 \

REPLICA_NUM=3 \

CPU_REQUEST="4000m" \

MEMORY_REQUEST="1024Mi" \

ENABLE_ISTIO_SIDECAR='false'

The dump-manifests target in the Makefile lets you output raw Kubernetes YAML files that can be used in different ways. You can apply these YAML files directly to a cluster using kubectl apply -f, making it easy to deploy changes manually. The same files also work well with tools like ArgoCD, Flux, or Spinnaker, giving you flexibility in how you manage deployments. This approach keeps things simple and avoids being locked into any specific tool or framework. The YAML files show exactly what will be deployed, making it easier to review, back up, or move between environments without surprises.

Using Make with tools like curl is a super flexible way to handle Kubernetes deployments, and it can easily replace some of the things Helm does. For example, instead of using Helm charts to manage releases, we’re just using kubectl in a Makefile to create and delete Kubernetes secrets. By running simple shell commands and using kubectl, we can manage things like versioning and configuration directly in Kubernetes without all the complexity of Helm. This approach gives us more control and is lighter weight, which is perfect for projects where you want simplicity and flexibility without the overhead of managing full Helm charts.

.PHONY: create-release

create-release:

@echo "Creating Kubernetes secret with VERSION set to Git commit SHA..."

@SECRET_NAME="app-version-secret"; \

JSON_DATA="{\"VERSION\":\"$(GIT_COMMIT)\"}"; \

kubectl create secret generic $$SECRET_NAME \

--from-literal=version.json="$$JSON_DATA" \

--dry-run=client -o yaml | kubectl apply -f -

@echo "Secret created successfully: app-version-secret"

.PHONY: remove-release

remove-release:

@echo "Deleting Kubernetes secret: app-version-secret..."

@SECRET_NAME="app-version-secret"; \

kubectl delete secret $$SECRET_NAME 2>/dev/null || true

@echo "Secret deleted successfully: app-version-secret"

Since the manifests array contains all the Kubernetes resource definitions, we can easily dump them into both YAML and JSON formats. The dump-manifests target runs make template to generate the YAML output and make convert-to-json to convert the same output into JSON. By redirecting the output to manifest.yaml and manifest.json, you're able to keep both versions of the resources for further use. It’s a simple and efficient way to generate multiple formats from the same set of manifests.

.PHONY: dump-manifests

dump-manifests: template convert-to-json

@echo "Dumping manifests to manifest.yaml and manifest.json..."

@make template > manifest.yaml

@make convert-to-json > manifest.json

@echo "Manifests successfully dumped to manifest.yaml and manifest.json."

With the validate-% target, you can easily validate any specific manifest by piping it through yq to check the structure or content in a readable format. This leverages external tools like yq to validate and process YAML directly within the Makefile, without needing to write complex scripts. Similarly, the print-% target allows you to quickly print the value of any Makefile variable, giving you an easy way to inspect variables or outputs. By using external tools like yq, you can enhance the flexibility of your Makefile, making it easy to validate, process, and manipulate manifests directly.

# Validates a specific manifest using `yq`.

validate-%:

@echo "$$$*" | yq eval -P '.' -

# Prints the value of a specific variable.

print-%:

@echo "$$$*"

With Makefile and simple Bash scripting, you can easily implement auxiliary functions like getting Vault keys. In this case, the get-vault-keys target lists available Vault pods, prompts for the pod name, and retrieves the Vault unseal key and root token by executing commands on the chosen pod. The approach uses basic tools like kubectl, jq, and Bash, making it much more flexible than dealing with Helm’s syntax or other complex tools. It simplifies the process and gives you full control over your deployment logic without having to rely on heavyweight tools or charts.

.PHONY: get-vault-keys

get-vault-keys:

@echo "Available Vault pods:"

@PODS=$$(kubectl get pods -l app.kubernetes.io/name=vault -o jsonpath='{.items[*].metadata.name}'); \

echo "$$PODS"; \

read -p "Enter the Vault pod name (e.g., vault-0): " POD_NAME; \

if echo "$$PODS" | grep -qw "$$POD_NAME"; then \

kubectl exec $$POD_NAME -- vault operator init -key-shares=1 -key-threshold=1 -format=json > keys.json; \

VAULT_UNSEAL_KEY=$$(cat keys_$$POD_NAME.json | jq -r ".unseal_keys_b64[]"); \

echo "Unseal Key: $$VAULT_UNSEAL_KEY"; \

VAULT_ROOT_KEY=$$(cat keys.json | jq -r ".root_token"); \

echo "Root Token: $$VAULT_ROOT_KEY"; \

else \

echo "Error: Pod '$$POD_NAME' not found."; \

fi

Constraints

When managing complex workflows, especially in DevOps or Kubernetes environments, constraints play a vital role in ensuring consistency, preventing errors, and maintaining control over the build process. In Makefiles, constraints can be implemented to validate inputs, restrict environment configurations, and enforce best practices. Let’s explore how this works with a practical example.

What Are Constraints in Makefiles?

Constraints are rules or conditions that ensure only valid inputs or configurations are accepted during execution. For instance, you might want to limit the environments (dev, sit, uat, prod) where your application can be deployed, or validate parameter files before proceeding with Kubernetes manifest generation.

Example: Restricting Environment Configurations

Consider the following snippet from the provided Makefile:

ENV ?= dev

ALLOWED_ENVS := global dev sit uat prod

ifeq ($(filter $(ENV),$(ALLOWED_ENVS)),)

$(error Invalid ENV value '$(ENV)'. Allowed values are: $(ALLOWED_ENVS))

endif

Here’s how this works:

Default Value : The ENV variable defaults to dev if not explicitly set.

Allowed Values : The ALLOWED_ENVS variable defines a list of valid environments.

Validation Check : The ifeq block checks if the provided ENV value exists in the ALLOWED_ENVS list. If not, it throws an error and stops execution.

For example:

Running make apply ENV=test will fail because test is not in the allowed list.

Running make apply ENV=prod will proceed as prod is valid.

This snippet validates that the MEMORY_REQUEST and MEMORY_LIMIT values are within the acceptable range of 128Mi to 4096Mi. It extracts the numeric value, converts units (e.g., Gi to Mi), and checks if the values fall within the specified bounds. If not, it raises an error to prevent invalid configurations from being applied.

# Validate memory ranges (e.g., 128Mi <= MEMORY_REQUEST <= 4096Mi)

MEMORY_REQUEST_VALUE := $(subst Mi,,$(subst Gi,,$(MEMORY_REQUEST)))

MEMORY_REQUEST_UNIT := $(suffix $(MEMORY_REQUEST))

ifeq ($(MEMORY_REQUEST_UNIT),Gi)

MEMORY_REQUEST_VALUE := $(shell echo $$(($(MEMORY_REQUEST_VALUE) * 1024)))

endif

ifeq ($(shell [ $(MEMORY_REQUEST_VALUE) -ge 128 ] && [ $(MEMORY_REQUEST_VALUE) -le 4096 ] && echo true),)

$(error Invalid MEMORY_REQUEST value '$(MEMORY_REQUEST)'. It must be between 128Mi and 4096Mi.)

endif

MEMORY_LIMIT_VALUE := $(subst Mi,,$(subst Gi,,$(MEMORY_LIMIT)))

MEMORY_LIMIT_UNIT := $(suffix $(MEMORY_LIMIT))

ifeq ($(MEMORY_LIMIT_UNIT),Gi)

MEMORY_LIMIT_VALUE := $(shell echo $$(($(MEMORY_LIMIT_VALUE) * 1024)))

endif

ifeq ($(shell [ $(MEMORY_LIMIT_VALUE) -ge 128 ] && [ $(MEMORY_LIMIT_VALUE) -le 4096 ] && echo true),)

$(error Invalid MEMORY_LIMIT value '$(MEMORY_LIMIT)'. It must be between 128Mi and 4096Mi.)

endif

Labels

Using Make for Kubernetes deployments offers greater flexibility compared to Helm, as it allows for fully customizable workflows without enforcing a rigid structure. While Helm is designed specifically for Kubernetes and provides a standardized templating system, it can feel restrictive for non-standard or highly dynamic use cases. With Make, you can dynamically generate lists of labels and annotations programmatically, avoiding the need to manually define them in manifests. This approach ensures consistency and reduces repetitive work by leveraging variables, environment data, and tools like Git metadata. Additionally, Make integrates seamlessly with external scripts and tools, enabling more complex logic and automation that Helm’s opinionated framework might not easily support.

Example:

# Extract Git metadata

GIT_BRANCH := $(shell git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD)

GIT_COMMIT := $(shell git rev-parse --short HEAD)

GIT_REPO_URL := $(shell git config --get remote.origin.url || echo "local-repo")

ENV_LABEL := app.environment:$(ENV)

GIT_BRANCH_LABEL := app.git/branch:$(GIT_BRANCH)

GIT_COMMIT_LABEL := app.git/commit:$(GIT_COMMIT)

GIT_REPO_LABEL := app.git/repo:$(GIT_REPO_URL)

TEAM_LABEL := app.team:devops

OWNER_LABEL := app.owner:engineering

DEPLOYMENT_LABEL := app.deployment:nginx-controller

VERSION_LABEL := app.version:v1.23.0

BUILD_TIMESTAMP_LABEL := app.build-timestamp:$(shell date -u +"%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ")

RELEASE_LABEL := app.release:stable

REGION_LABEL := app.region:us-west-2

ZONE_LABEL := app.zone:a

CLUSTER_LABEL := app.cluster:eks-prod

SERVICE_TYPE_LABEL := app.service-type:LoadBalancer

INSTANCE_LABEL := app.instance:nginx-controller-instance

# Combine all labels into a single list

LABELS := \

$(ENV_LABEL) \

$(GIT_BRANCH_LABEL) \

$(GIT_COMMIT_LABEL) \

$(GIT_REPO_LABEL) \

$(TEAM_LABEL) \

$(OWNER_LABEL) \

$(DEPLOYMENT_LABEL) \

$(VERSION_LABEL) \

$(BUILD_TIMESTAMP_LABEL) \

$(RELEASE_LABEL) \

$(REGION_LABEL) \

$(ZONE_LABEL) \

$(CLUSTER_LABEL) \

$(SERVICE_TYPE_LABEL) \

$(INSTANCE_LABEL) \

$(DESCRIPTION_LABEL)

define generate_labels

$(shell printf " %s\n" $(patsubst %:,%: ,$(LABELS)))

endef

# Example target to print the labels in YAML format

print-labels:

@echo "metadata:"

@echo " labels:"

@$(foreach label,$(LABELS),echo " $(shell echo $(label) | sed 's/:/=/; s/=/:\ /')";)

This will output:

make -f test.mk

metadata:

labels:

app.environment:

app.git/branch: main

app.git/commit: 0158245

app.git/repo: https://github.com/avkcode/vault.git

app.team: devops

app.owner: engineering

app.deployment: nginx-controller

app.version: v1.23.0

app.build-timestamp: 2025-04-22T12:38:58Z

app.release: stable

app.region: us-west-2

app.zone: a

app.cluster: eks-prod

app.service-type: LoadBalancer

app.instance: nginx-controller-instance

Using with manifests:

define deployment

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

$(call generate_labels)

name: release-name-ingress-nginx-controller

namespace: default

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: ingress-nginx

app.kubernetes.io/instance: release-name

app.kubernetes.io/component: controller

replicas: 1

...

endef

export deployment

With general-purpose coding, dynamically generating labels based on parameters like target environment (DEV/PROD/STAGE) is straightforward—just define rules and inject values at runtime. Tools aren't needed for such simple string manipulation.

make validate-configmap

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

labels: app.environment:dev app.git/branch:main app.git/commit:af4eae9 app.git/repo:https://github.com/avkcode/nginx.git app.team:devops app.critical:false app.sla:best-effort

name: release-name-ingress-nginx-controller

namespace: default

By default DEV dev app.team:devops app.critical:false app.sla:best-effort

Adds app.team:devops app.critical:true app.sla:tier-1

ENV=prod make validate-configmap

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

labels: app.environment:prod app.git/branch:main app.git/commit:af4eae9 app.git/repo:https://github.com/avkcode/nginx.git app.team:devops app.critical:true app.sla:tier-1

name: release-name-ingress-nginx-controller

namespace: default

Code:

# Validate and set environment

VALID_ENVS := dev sit uat prod

ENV ?= dev

ifeq ($(filter $(ENV),$(VALID_ENVS)),)

$(error Invalid ENV. Valid values are: $(VALID_ENVS))

endif

# Environment-specific settings

ifeq ($(ENV),prod)

APP_PREFIX := prod

EXTRA_LABELS := app.critical:true app.sla:tier-1

else ifeq ($(ENV),uat)

APP_PREFIX := uat

EXTRA_LABELS := app.critical:false app.sla:tier-2

else ifeq ($(ENV),sit)

APP_PREFIX := sit

EXTRA_LABELS := app.critical:false app.sla:tier-3

else

APP_PREFIX := dev

EXTRA_LABELS := app.critical:false app.sla:best-effort

endif

# Extract Git metadata

GIT_BRANCH := $(shell git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD)

GIT_COMMIT := $(shell git rev-parse --short HEAD)

GIT_REPO := $(shell git config --get remote.origin.url)

ENV_LABEL := app.environment:$(ENV)

GIT_BRANCH_LABEL := app.git/branch:$(GIT_BRANCH)

GIT_COMMIT_LABEL := app.git/commit:$(GIT_COMMIT)

GIT_REPO_LABEL := app.git/repo:$(GIT_REPO)

TEAM_LABEL := app.team:devops

LABELS := \

$(ENV_LABEL) \

$(GIT_BRANCH_LABEL) \

$(GIT_COMMIT_LABEL) \

$(GIT_REPO_LABEL) \

$(TEAM_LABEL) \

$(EXTRA_LABELS)

define generate_labels

$(shell printf " %s\n" $(patsubst %:,%: ,$(LABELS)))

endef

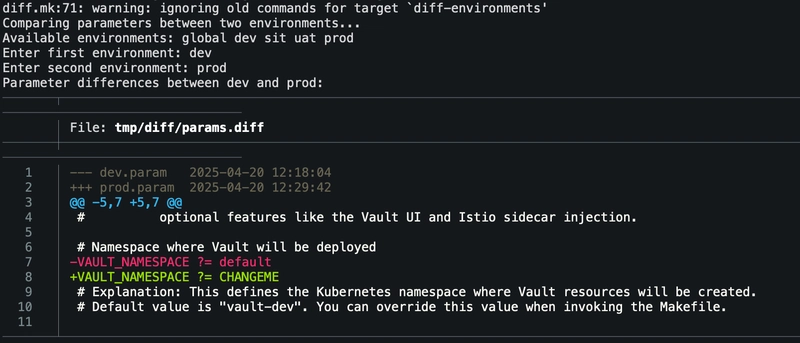

diff

Advanced diff capabilities to compare Kubernetes manifests across different states: live cluster vs generated, previous vs current, git revisions, and environments.

- diff - Interactive diff menu

- diff-live - Compare live cluster vs generated manifests

- diff-previous - Compare previous vs current manifests

- diff-revisions - Compare between git revisions

- diff-environments - Compare manifests across environments

- diff-params - Compare parameter files between environments

Helm charts

If you’re absolutely required to distribute a Helm chart but don’t have one pre-made, no worries—it’s totally possible to generate one from the manifests produced by this Makefile. The gen_helm_chart.py script (referenced via include helm.mk) automates this process. It takes the Kubernetes manifests generated by the Makefile and packages them into a Helm chart. This way, you can still meet the requirement for a Helm chart while leveraging the existing templates and workflows in the Makefile.

Releases

The Makefile approach to managing releases offers a streamlined and transparent alternative to tools like Helm, focusing on simplicity and direct control over the deployment process. Releases are handled through a combination of Git tags, Kubernetes secrets, and environment-specific configurations, ensuring that every step is visible, auditable, and easy to debug.

Releases are initiated by creating a Git tag, which serves as an immutable reference point for the deployed version. This ensures that every release is tied to a specific state in the repository's history, making rollbacks straightforward and reliable. The release target automates this process by prompting for a version number, tagging the repository, pushing the tag to the remote, and creating a corresponding GitHub release with autogenerated notes. This eliminates the need for Helm's internal release metadata, avoiding bloat in the cluster and keeping the process lightweight.

.PHONY: release

release:

@echo "Creating Git tag and releasing on GitHub..."

@read -p "Enter the version number (e.g., v1.0.0): " version; \

git tag -a $$version -m "Release $$version"; \

git push origin $$version; \

gh release create $$version --generate-notes

@echo "Release $$version created and pushed to GitHub."

.PHONY: create-release

create-release:

@echo "Creating Kubernetes secret with VERSION set to Git commit SHA..."

@SECRET_NAME="app-version-secret"; \

JSON_DATA="{\"VERSION\":\"$(GIT_COMMIT)\"}"; \

kubectl create secret generic $$SECRET_NAME \

--from-literal=version.json="$$JSON_DATA" \

--dry-run=client -o yaml | kubectl apply -f -

@echo "Secret created successfully: app-version-secret"

.PHONY: remove-release

remove-release:

@echo "Deleting Kubernetes secret: app-version-secret..."

@SECRET_NAME="app-version-secret"; \

kubectl delete secret $$SECRET_NAME 2>/dev/null || true

@echo "Secret deleted successfully: app-version-secret"

.PHONY: show-release

show-release:

@SECRET_NAME="app-version-secret"; \

kubectl get secret $$SECRET_NAME -o jsonpath='{.data.version\.json}' | base64 --decode | jq -r .VERSION

Validate

The Makefile-based validation approach provides a clear and direct method for ensuring the correctness of Kubernetes manifests. Unlike Helm which often obscures the actual YAML behind layers of templating logic and requires specific commands like helm template or helm lint to validate charts, the Makefile approach allows for explicit validation of individual manifests using standard tools like yq. This makes it easier to identify and fix issues since there are no hidden abstractions or complex dependency chains to navigate.

The validation process in Makefiles is tightly integrated with the deployment workflow. Specific targets like validate-% enable focused validation of particular resources while server-side and client-side validation targets provide comprehensive checks against the Kubernetes API. These validation steps can be seamlessly incorporated into CI/CD pipelines without requiring additional tooling or plugins, offering a more native and flexible solution compared to Helm's specialized requirements.

Furthermore, the Makefile approach avoids complications such as Helm release metadata bloat or stateful upgrade surprises that can interfere with validation. Since manifests remain in their raw form and changes are tracked through Git, the validation process benefits from version control transparency and an immutable history. This ensures that any rollback or differential validation is straightforward and reliable, unlike Helm's dependency on internal state stored in cluster secrets. The result is a simpler yet robust validation mechanism that aligns with the principle of keeping Kubernetes deployments transparent and maintainable.

Specific Manifest Validation

The validate-% target allows validation of individual manifests. It takes a manifest name as an argument and processes it through yq to check its structure and syntax.

validate-%:

@echo "$$$*" | yq eval -P '.' -

Server-Side Validation

The validate-server target performs server-side validation of all manifests against the Kubernetes API. This ensures that manifests are compatible with the actual cluster configuration. Each manifest is converted to JSON using yq and then validated using kubectl apply with the --dry-run=server option.

.PHONY: validate-server

validate-server:

@echo "Validating JSON manifests against the Kubernetes API (server-side validation)..."

@$(foreach manifest,$(manifests), \

echo "Validating manifest: $(manifest)" && \

printf '%s' "$(manifest)" | yq eval -o=json -P '.' - | kubectl apply --dry-run=server -f - || exit 1; \

)

@echo "All JSON manifests passed server-side validation successfully."

Client-Side Validation

The validate-client target conducts client-side validation of all manifests against the Kubernetes API. Similar to server-side validation, each manifest is converted to JSON format and checked using kubectl apply but with the --dry-run=client option. This provides a quick validation without contacting the API server.

.PHONY: validate-client

validate-client:

@echo "Validating JSON manifests against the Kubernetes API (client-side validation)..."

@$(foreach manifest,$(manifests), \

echo "Validating manifest: $(manifest)" && \

printf '%s' "$(manifest)" | yq eval -o=json -P '.' - | kubectl apply --dry-run=client -f - || exit 1; \

)

@echo "All JSON manifests passed client-side validation successfully."

Feature flags

Flags that can be toggled on/off per environment. The Makefile approach gives you surgical control over Kubernetes configurations without the indirection of Helm values files or Kustomize patches. Here's how we can extend the environment-specific constraints with feature flags:

# Feature flags - enabled by environment

ENABLED_FEATURES := \

$(if $(filter prod uat,$(ENV)),monitoring) \

$(if $(filter prod,$(ENV)),auto-scaling) \

$(if $(filter dev sit,$(ENV)),debug-tools)

# Conditional includes based on features

ifeq ($(filter monitoring,$(ENABLED_FEATURES)),monitoring)

include monitoring.mk

endif

ifeq ($(filter auto-scaling,$(ENABLED_FEATURES)),auto-scaling)

include hpa.mk

endif

| Feature | dev | sit | uat | prod |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| monitoring | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| auto-scaling | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| debug-tools | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

The real power comes when combining this with the GitOps flow:

Git Blame for Infrastructure Changes

$ git blame Makefile

^d34172a (Alice Devops 2024-03-15 14:22:03 -0500 1) # Feature flags by environment

d34172a (Alice Devops 2024-03-15 14:22:03 -0500 2) ENABLED_FEATURES := \

a5f2e1b (Bob Security 2024-04-01 09:15:47 -0500 3) $(if $(filter prod uat,$(ENV)),monitoring) \

a5f2e1b (Bob Security 2024-04-01 09:15:47 -0500 4) $(if $(filter prod,$(ENV)),auto-scaling) \

c8e441d (Carol Platform 2024-04-20 16:33:12 -0500 5) $(if $(filter dev sit,$(ENV)),debug-tools)

Ingress

The Makefile-based approach simplifies the deployment of Kubernetes ingress resources by consolidating all necessary components into a single, coherent workflow. This method eliminates the need for external tools or complex integrations, allowing you to manage the entire stack through straightforward make commands. The Makefile incorporates definitions for service accounts, roles, role bindings, and ingress-specific configurations, ensuring proper access controls and networking setup. By leveraging environment variables and templating, it dynamically generates the required Kubernetes manifests while maintaining consistency across deployments. This unified approach enables seamless integration between infrastructure provisioning, application deployment, and network configuration, providing a transparent and maintainable solution for managing ingress resources within your Kubernetes environment.

To incorporate the ingress-related Makefile functionality using include, you can structure your Makefile to pull in external files that define various components like service accounts, roles, bindings, and other Kubernetes resources. This allows for better modularity, reusability, and clarity in your deployment pipeline.

Here’s an example of how you can use include to organize and include different parts of your ingress stack:

.

├── Makefile

├── global.param

├── ingress.mk

├── rbac.mk

├── configmap.mk

└── params/

├── dev.param

├── prod.param

└── uat.param

By structuring your Makefile this way, you can easily manage complex deployments while keeping everything modular and transparent.

Bundle and Archive Targets

When managing Kubernetes deployments, it's often necessary to create portable archives or bundles of your deployment artifacts. These can be used for backups, sharing configurations, or deploying to environments without direct access to your Git repository. The Makefile includes targets like archive and bundle to simplify this process.

Archive Target

The archive target creates a compressed .tar.gz file containing all the necessary files for your deployment. This is especially useful for creating snapshots of your configuration at a specific point in time.

Bundle Target

The bundle target creates a Git bundle, which is a single file containing the entire Git repository history up to a specific commit. This is particularly useful for transferring repositories between systems without direct network access.

Why Use Archive and Bundle?

- Portability : Both archive and bundle produce single files that are easy to transfer and store.

- Version Control : The bundle target preserves Git history, allowing you to track changes even when offline.

- Reproducibility : The archive target ensures that you can reproduce the exact state of your deployment at any time.

- Backup : These targets are excellent for creating backups of your deployment configuration.

Conclusion

Sometimes, the simplest way of using just Unix tools is the best way. By relying on basic utilities like kubectl, jq, yq, and Make, you can create powerful, customizable workflows without the need for heavyweight tools like Helm. These simple, straightforward scripts offer greater control and flexibility. Plus, with LLMs (large language models) like this one, generating and refining code has become inexpensive and easy, making automation accessible. However, when things go wrong, debugging complex tools like Helm can become exponentially more expensive in terms of time and effort. Using minimal tools lets you stay in control, reduce complexity, and make it easier to fix issues when they arise. Sometimes, less really is more.

Other examples of usage:

Top comments (0)