The web is no longer just a collection of static text documents with a few images and GIFs thrown into the mix. Over the last twenty years or so, we’ve seen the web coalesce into a slurry of web apps small and large, each one more complex and dynamic than the last, strung together with APIs, scripts, and more data than anyone could have ever imagined.

For web developers, it can be overwhelming to keep up, despite being knee-deep in those technologies every single day. And in our perennial quest to stay current, a lot of things get left behind.

One of the easiest things to forget about — but arguably one of the most important — is accessibility. Just as the web itself has grown, so has the sheer number and diversity of its users. Everyone from kids to seniors, with varying degrees of ability and disability, rely on the web for shopping, entertainment, education, and even life-providing medical information and supplies.

But accessibility isn’t just about disabled users, though they are often the focus. Accessibility is about opening the web to everyone. The folks over at 18F put it well:

Accessibility is one of the most important aspects of modern web development. Accessibility means the greatest number of users can view your content. It means search engines will be able to read your site more completely. Users of all types will have a better experience if you take accessibility concerns into account.

Keeping increasingly complex web apps accessible is a necessity. Fortunately, there is one thing you can do to keep any web app accessible to as many users as possible, and lessen the burden of development and maintenance for yourself, too.

Just use text.

LogRocket is working on the perfect front-end bug report. Click to check it out.

Text wins

In the early days of the web, nearly everything was text, marked up with a fairly limited number of HTML tags. In fact, it wasn’t untilMarc Andreessen introduced the img tag into Mosaic in 1993 that inline images inside of web pages became available (previously images were accessed through hyperlinks).

While images opened up and helped popularize the web, the heart of the web was — and still is — text. Every web document is text, regardless of what else is included with it. HTML, text. CSS, text. JavaScript, text. Hell, the protocols that transmit all of that information are declared via text.

The only thing that has changed is how complex we make that text.

But text is still the way to build the web. Even as more content is delivered via images, videos, and audio, text is the single best way to keep that content accessible to the widest range of users. That’s because text is easily:

- Read by users

- Read by machines (search engines, screen readers, etc.)

- Translated

- Styled

- Zoomed

- And edited

Additionally, text files are typically much lighter than images, audio, and video. Text helps ease the burden on users with limited bandwidth or slow connections, helping to fight the bloat in modern websites, something Nick Heer recently referred to as The Bullshit Web. This combination of increased performance and accessible features makes the original foundation of the web hard to beat.

If we all agree that text is the most usable element on the web, then how can we ensure that our web apps and the content they deliver best put it to work?

Semantic markup

When delivering text to users, we include it in the HTML document. Although the earliest days of the web relied on around 18 tags to markup those documents, we now have access to over 100 tags when creating our documents.

Many of the tags introduced in HTML5 focus on providing added semantics to make it clearer to users and machines what that content is. Tags like section, article, nav, header, footer, and aside better describe their content. Combined with old standards like p, strong, and all of the headings, we can confidently mark up content knowing that it will be accessible to more users than ever before.

When building your own pages and applications, you should strive to keep as much content as possible in semantic markup.

You can always add additional functionality to those tags using things like ARIA roles or data attributes, but the core of your application should rely on semantic elements for marking up content.

It’s easy to see how headings and paragraphs work for blocks of copy, but what about more complicated application features like data tables, cards, notifications, tooltips, and menu buttons? There are some solid patterns that can be used to build those features.

- Heydon Pickering’sInclusive Components is one of the best, going into detail about how to craft many of those components.

- Dave Rupert’sNutrition Cards for Accessible Components is new, but a great and growing resource for understanding how some of those common components should properly function.

- The A11Y Project’s Patterns list is a great roundup of links.

- Marcy Sutton has acool presentation on the topic.

- And, when in doubt, you can always refer back tothis helpful guide from Addy Osmani.

Even with those complex components, the underlying principle is the same: Use semantic markup. If you’re building something wildly complex that no one has ever seen before, sit down, map out what the child elements of that component are, and try to use semantic markup for those child elements.

Styling accessible text

Once you have your text marked up with semantic tags, you need to style it. Thankfully, there areclear guidelines for styling your text so that it’s accessible to everyone.

The first thing you should do is ensure that your text is zoomable. Many users with low-vision use browser or OS-level zoom controls to bump up the text size on their screens. But some developers still disable zoom on web pages with the following:

<meta name=”viewport” content=”initial-scale=1, maximum-scale=1">

When set the same as the initial scale, maximum-scale prevents users from enlarging the text. Keeping text zoomable is therefore easy: Just remove that value.

When it comes to the actual styling of text, the main things you want to consider are size and contrast.

The main consideration is making text easy to ready without forcing users to zoom in. A baseline font size of 14px is recommended, but larger than that is often better.

For contrast, the rule is simple, as specified inGuideline 1.4 of the WCAG 2.0 Recommendation:

Make it easier for users to see and hear content including separating foreground from background.

The Guideline goes on to make recommendations on not using color as the only means of conveying information, minimum contrast ratios, and even text resizing, but the idea is simple: Clearly contrast text from its background. That means keeping text large and either dark enough (when on a light background) or light enough (when on a dark background). There are a few tools for checking contrast, includingWebAIM’s Color Contrast Checker and even tools for the design phase, likeStark for Sketch.

There’s a lot more that goes into designing and styling text, but I’ll leave it to you to dig into that topic on your own. Hint:Here’s a good starting point.

Text and images

Images still serve a vital role in conveying information and creating a more enjoyable experience for users. But, you need to keep your images just as accessible as the rest of your application.

To do that, you should use alternative (ALT) text on your img tags. ALT text provides some context for the content of images so that users with low-vision can better understand what’s in the image, typically when using assistive technology like screen readers. You use ALT text by adding the alt attribute with a value of the text equivalent of your image, like so:

<img src=“https://example.com/image.png” alt=“developer in an office working feverishly to hit a deadline on a software project” />

Even when working with icons or icon fonts, you can keep them accessible using text. Decorative icons (ones that don’t convey vital information) should still use the alt attribute but keep the value empty. Then you can apply the aria-hidden attribute to ensure that it’s ignored by screen readers:

<img src=“https://example.com/icon.svg” alt=“” aria-hidden />

But for non-decorative icons, you can keep them accessible by either using ALT text on the image or loading the icon using CSS with HTML text as a hidden fallback for screen readers, similar to howFont Awesome does it:

<i aria-hidden class=”fas fa-car” title=”Time to destination by car”></i>

<span class=”sr-only”>Time to destination by car:</span>

<span>4 minutes</span>

The icon is loaded via CSS on the i tag, which includes a title for mouse users. The span immediately following is hidden with CSS, but is still available to screen readers. It’s a clever solution, one that bothCSS-Tricks andThe Filament Group support (with a few variations for good measure).

Writing effective ALT text is an art form in itself. Thankfully, there are some great resources out there, one of the best being WebAIM’s Alternative Text guide.

Accessibility and frameworks

Although JavaScript frameworks like React and Vue are changing the way many developers build web applications, they don’t change the need for those applications to remain accessible to a wide variety of users. They just introduce a few complications for us. But we can keep those framework-driven apps accessible by following a simple rule:

Don’t let the framework force you into poor choices.

While frameworks like React do have suggested ways of accomplishing things, they don’t generally force you into abandoning non-semantic HTML — that’s the developer’s choice. It’s up to you to create thoughtful, well-designed, and accessible components, so stick to the fundamentals of semantic HTML.

A good example of this can be taken from React’s own documentation.When discussing components and props, they use a comment as an example:

What if we replaced some of those div elements with more descriptive HTML tags?

As suggested by MDN, the comment could be more semantically described with the article element, with the comment text being a paragraph. Additionally, the comment date could be marked up with the more semantic time element, which could even include the machine-readable version of the comment publication date in the datetime attribute. Depending on your application’s page hierarchy, you could change the user’s name to be a heading. Or, how about making the entire user info section a figure and using figcaption to markup the name?

Frameworks like React also have a few gotchas that you need to worry about when attempting to keep your apps accessible. In particular, React reserves keywords that can sometimes add confusion or break accessibility. A good example of this is when building forms.

Accessible forms will always include labels for inputs, which clearly describe what that input is to be used for. In HTML, the label and input are linked with the for attribute and an id on the input itself. Since for is a reserved keyword in JavaScript, you need to use htmlFor instead. The same thing applies to class, which becomes className.

But, when using ARIA attributes in React, you don’t need to camelCase them. Fortunately, they are fully supported in JSX, so including something like aria-hidden in an icon component works perfectly.

Keep your apps accessible

In the U.S. alone,over 18% of the population have some sort of disability and the saying, “At some point, we’ll all be disabled” is true. Whether you experience a temporary or permanent disability, you’ll likely be faced with challenges when using digital technology at some point in your life.

As developers, we’re in a unique position. We can choose to either help people or hinder them. Regardless, we will impact their lives in some way. By being more deliberate in our choices as developers, especially by favoring text and thoughtful, semantic markup, we have the power to improve the lives of a lot of people. So take some time to think about your applications and the techniques you use to build them.

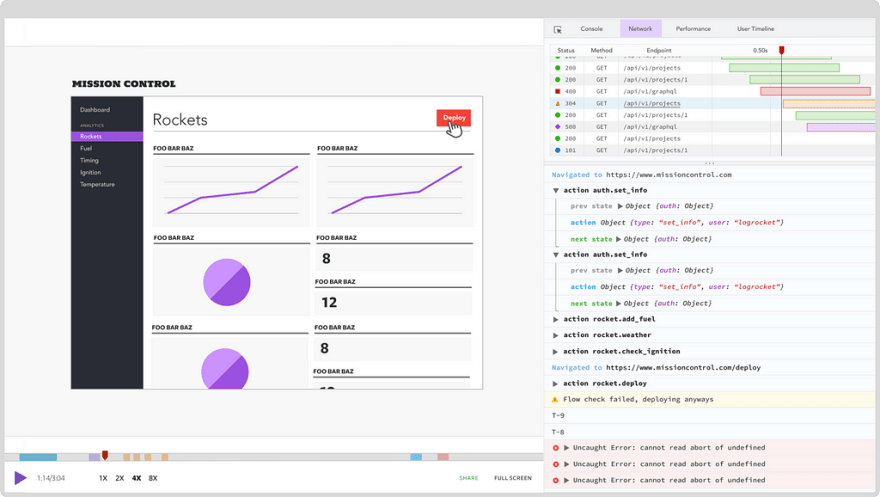

Plug: LogRocket, a DVR for web apps

LogRocket is a frontend logging tool that lets you replay problems as if they happened in your own browser. Instead of guessing why errors happen, or asking users for screenshots and log dumps, LogRocket lets you replay the session to quickly understand what went wrong. It works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

In addition to logging Redux actions and state, LogRocket records console logs, JavaScript errors, stacktraces, network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. It also instruments the DOM to record the HTML and CSS on the page, recreating pixel-perfect videos of even the most complex single page apps.

Top comments (0)