Originally published at deepu.tech.

So I started learning Rust a while ago and since my post about what I thought of Go was popular, I decided to write about what my first impressions of Rust were as well.

But unlike Go, I actually didn't build any real-world application in Rust, so my opinions here are purely personal and some might not be accurate as I might have misunderstood something. So do give me the consideration of a Rust newbie. If you find something I said here is inaccurate please do let me know. Also, my impressions might actually change once I start using the language more. If it does, I'll make sure to update the post.

As I have said in some of my other posts, I consider myself to be more pragmatic than my younger self now. Some of the opinions are also from that pragmatic perspective(or at least I think so).

I have weighed practicality, readability, and simplicity over fancy features, syntax sugars, and complexity. Also, some things which I didn't like but found not such a big deal are put under nitpicks rather than the dislike section as I thought it was fairer that way.

One thing that sets Rust apart from languages like Go is that Rust is not garbage collected, and I understand that many of the language features/choices where designed with that in mind.

Rust is primarily geared towards procedural/imperative style of programming but it also lets you do a little bit of functional and object-oriented style of programming as well. And that is my favorite kind of mix.

So, without any further ado, let's get into it.

What I like about Rust

Things that I really liked, in no particular order.

No Garbage collection

One of the first things you would notice in Rust, especially if you are coming from garbage collected languages like Java or Golang is the lack of garbage collection. Yes, there is no GC in Rust, then how does it ensure my program runs efficiently in the given memory and how does it prevent out of memory errors?

Rust has something called ownership, so basically any value in Rust must have a variable as its owner(and only one owner at a time) when the owner goes out of scope the value will be dropped freeing the memory regardless of it being in stack or heap memory. For example, in the below example the value of foo is dropped as soon as the method execution completes and the value of bar is dropped right after the block execution.

fn main() {

let foo = "value"; // owner is foo and is valid within this method

{

let bar = "bar value"; // owner is bar and is valid within this block scope

println!("value of bar is {}", bar); // bar is valid here

}

println!("value of foo is {}", foo); // foo is valid here

println!("value of bar is {}", bar); // bar is not valid here as its out of scope

}

So by scoping variables carefully, we can make sure the memory usage is optimized and that is also why Rust lets you use block scopes almost everywhere.

Also, the Rust compiler helps you in dealing with duplicate pointer references and so on. The below is invalid in Rust since foo is now using heap memory rather than stack and assigning a reference to a variable is considered a move. If deep copying(expensive) is required it has to be performed using the clone function which performs a copy instead of move.

fn main() {

let foo = String::from("hello"); // owner is foo and is valid within this method

{

let bar = foo; // owner is bar and is valid within this block scope, foo in invalidated now

println!("value of bar is {}", bar); // bar is valid here

}

println!("value of foo is {}", foo); // foo is invalid here as it has moved

}

The ownership concept can be a bit weird to get used to, especially since passing a variable to a method will also move it(if its not a literal or reference), but given that it saves us from GC I think its worth it and the compiler takes care of helping us when we make mistakes.

Immutable by default

Variables are immutable by default. If you want to mutate a variable you have to specifically mark it using the mut keyword.

let foo = "hello" // immutable

let mut bar = "hello" // mutable

Variables are by default passed by value, in order to pass a reference we would have to use the & symbol. Quite similar to Golang.

fn main() {

let world = String::from("world");

hello_ref(&world); // pass by reference. Keeps ownership

// prints: Hello world

hello_val(world); // pass by value and hence transfer ownership

// prints: Hello world

}

fn hello_val(msg: String) {

println!("Hello {}", msg);

}

fn hello_ref(msg: &String) {

println!("Hello {}", msg);

}

When you pass a reference it is still immutable so we would have to explicitly mark that mutable as well as below. This makes accidental mutations very difficult. The compiler also ensures that we can only have one mutable reference in a scope.

fn main() {

let mut world = String::from("world");

hello_ref(&mut world); // pass by mutable reference. Keeps ownership

// prints: Hello world!

hello_val(world); // pass by value and hence transfer ownership

// prints: Hello world!

}

fn hello_val(msg: String) {

println!("Hello {}", msg);

}

fn hello_ref(msg: &mut String) {

msg.push_str("!"); // mutate string

println!("Hello {}", msg);

}

Pattern matching

Rust has first-class support for pattern matching and this can be used for control flow, error handling, variable assignment and so on. pattern matching can also be used in if, while statements, for loops and function parameters.

fn main() {

let foo = String::from("200");

let num: u32 = match foo.parse() {

Ok(num) => num,

Err(_) => {

panic!("Cannot parse!");

}

};

match num {

200 => println!("two hundred"),

_ => (),

}

}

Generics

One thing I love in Java and TypeScript is the generics. It makes static typing more practical and DRY. Strongly typed languages(Looking at you Golang) without generics are annoying to work with. Fortunately, Rust has great support for generics. It can be used in types, functions, structs, and enums. The icing on the cake is that Rust converts the Generic code using specific code during compile time thus there is no performance penalty in using them.

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

fn hello<T>(val: T) -> T {

return val;

}

fn main() {

let foo = hello(5);

let foo = hello("5");

let integer = Point { x: 5, y: 10 };

let float = Point { x: 1.0, y: 4.0 };

}

Static types and advanced type declarations

Rust is a strictly typed language with a static type system. It also has great type inference which means we don't have to define types manually for everything. Rust also allows for complex type definitions.

type Kilometers = i32;

type Thunk = Box<dyn Fn() + Send + 'static>;

type Result<T> = std::result::Result<T, std::io::Error>;

Nice and simple error handling

Error handling in Rust is quite nice, there are recoverable and unrecoverable errors. For recoverable errors, you can handle them using pattern matching on the Result enum or using the simple expect syntax. There is even a shorthand operator to propagate errors from a function. Take that Go.

use std::fs::File;

fn main() {

let f = File::open("hello.txt").expect("Failed to open hello.txt");

// or

let f = match File::open("hello.txt") {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(error) => {

panic!("Problem opening the file: {:?}", error)

},

};

}

Tuples

Rust has built-in support for tuples, and this is highly helpful when you have to return multiple values from a function or when you want to unwrap a value and so on.

Block expressions

In Rust, you can have block expressions with their own scope almost anywhere. It also lets you assign a variable value from block expressions, if statement, loops and so on.

fn main() {

let foo = {

println!("Assigning foo");

5

};

let bar = if foo > 5 { 6 } else { 10 };

}

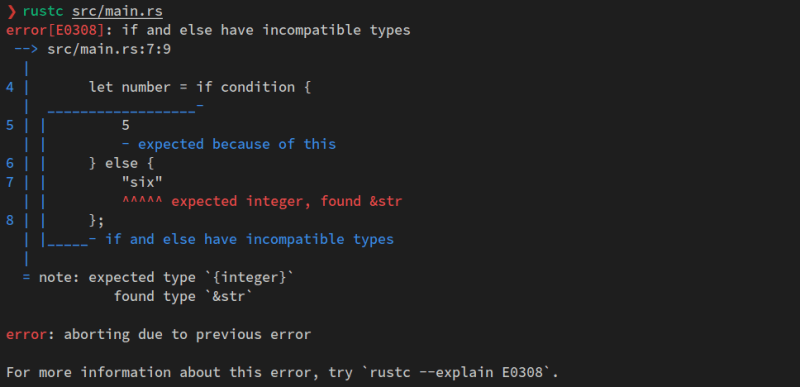

Beautiful compiler output

Rust simply has the best error output during compilation that I have seen. It can't get better than this I think. It is so helpful.

Built-in tooling

Like many modern programming languages, Rust also provides a lot of build-in standard tooling and honestly, I think this is one of the best that I have come across. Rust has Cargo which is the built-in package manager and build system. It is an excellent tool. It takes care of all common project needs like compiling, building, testing and so on. It can even create new projects with a skeleton and manage packages globally and locally for the project. That means you don't have to worry about setting up any tooling to get started in Rust. I love this, it saves so much time and effort. Every programming language should have this.

Rust also provides built-in utilities and asserts to write tests which then can be executed using Cargo.

In Rust, related functionality is grouped into modules, modules are grouped together into something called crates and crates are grouped into packages. We can refer to items defined in one module from another module. Packages are managed by cargo. You can specify external packages in the Cargo.toml file. Reusable public packages can be published to the crates.io registry.

There are even offline built-in docs that you can get by running rustup docs and rustup docs --book which is amazing. Thanks to Mohamed ELIDRISSI for pointing it out to me.

Concurrency

Rust has first-class support for memory safe concurrent programming. Rust uses threads for concurrency and has 1:1 threading implementation. i.e, 1 green thread per operating system thread. Rust compiler guarantees memory safety while using the threads. It provides features like waiting for all threads to finish, sharing data with move closures or channels(similar to Go). It also lets you use shared state and sync threads.

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

fn main() {

thread::spawn(|| {

for i in 1..10 {

println!("hi number {} from the spawned thread!", i);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1));

}

});

for i in 1..5 {

println!("hi number {} from the main thread!", i);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1));

}

}

Macros and meta-programming

While I don't like all aspects of macros in Rust, there are more things to like here than dislike. The annotation macros, for example, are quite handy. Not a fan of the procedure macros though. For advanced users, you can write your own macro rules and do metaprogramming.

Traits

Traits are synonymous to interfaces in Java, it is used to define shared behaviors that can be implemented on structs. Traits can even specify default methods. The only thing I dislike here is the indirect implementation.

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String;

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("(Read more from {}...)", self.summarize_author())

}

}

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String {

format!("@{}", self.author)

}

}

fn main() {

let article = NewsArticle {

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from(

"The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best hockey team in the NHL.",

),

};

println!("New article available! {}", article.summarize());

}

Ability to use unsafe features if required

- Useful in advanced use-cases where you know what you are doing. A necessary evil IMO. I like it since its doable only within an

unsafe { }block making it very explicit. I would have moved this to the dislike section if that was not the case. - When you use these, the Rust compiler cannot guarantee memory and runtime safety and you are on your own to get this right. So definitely for advanced and experienced users.

What I don't like about Rust

Things that I didn't like very much, in no particular order.

Complexity

I don't like it when a language offers multiple ways to do the same things. This is one think Golang does pretty well, there are no two ways to do the same thing and hence it is easier for people to work on larger codebases and to review code. Also, you don't have to always think of the best possible way to do something. Unfortunately, Rust does this and I'm not a fan of it. IMO it makes the language more complex.

- Too many ways for iterations -> loops, while, for, iterators.

- Too many ways for creating procedures -> Functions, closures, macros

Edit: Based on discussions here and on Reddit, I say my perception of complexity only have increased. It seems like once you get past all the niceties there are a lot of things that would take some time to wrap your head around. I'm pretty sure if you are experienced in Rust, it would be a cakewalk for you but the language indeed is quite complex, especially the ways functions and closures behave in different contexts, lifetimes in structs and stuff.

Shadowing of variables in the same context

So Rust lets you do this

{

let foo = "hello";

println!("{}", foo);

let foo = "world";

println!("{}", foo);

}

- Kind of beats being immutable by default(I understand the reasoning of being able to perform transformations on an immutable variable, especially when passing references to a function and getting it back)

- IMO lets people practice bad practices unintentionally, I would have rather marked the variable mutable as I consider the above mutation as well.

- You can as easily accidentally shadow a variable as you would accidentally mutate one in Languages like JavaScript

- Gives people a gun to shoot in the foot

Edit: I saw a lot of comments here and on Reddit explaining why this is good. While I agree that it is useful in many scenarios, so is the ability of mutation. I think it would have been perfectly fine not to have this and people would have still loved Rust and all of them would have defended the decision not have this. So my opinion on this hasn't changed.

Functions are not first-class citizens

While it is possible to pass a function to another they are not exactly first-class citizens like in JavaScript or Golang. You cannot create closures from functions and you cannot assign functions to variables. Closures are separate from functions in Rust, they are quite similar to Java lambdas from what I see. While closures would be sufficient to perform some of the functional style programming patterns it would have been much nicer if it was possible using just functions thus making language a bit more simple.

Edit: Oh boy! this opinion triggered a lot of discussions here and on Reddit. So seems like Functions and closures are similar and different based on context, It also seems like Functions are almost like first-class citizens, but if you are used to languages like Go or JavaScript where functions are much more straight forward then you are in for a crazy ride. Functions in Rust seems much much more complex. A lot of people who commented seemed to miss the fact that my primary complaint was that having two constructs(closures and functions) that look and act quite similar in most of the scenarios makes things more complex. At least in Java and JS where there are multiple constructs(arrow functions, lambdas) those where due to the fact that they were added much later to the language and those are still something I don't like in those languages. The best explanation was from Yufan Lou and another from zesterer. I'm not gonna remove this from stuff I don't like since I still don't like the complexity here.

Implicit implementation of traits

I'm not a fan of implicit stuff as its easier to abuse this and harder to read. You could define a struct in one file and you could implement a trait for that struct in another file which makes it less obvious. I prefer when the implementation is done by intent like in Java which makes it more obvious and easier to follow. While the way in Rust is not ideal, it is definitely better than Golang which is even more indirect.

Nitpicks

Finally some stuff I still don't like but I don't consider them a big deal.

-

I don't see the point of having theDiane pointed out the differenceconstkeyword whenletis immutable by default. It seems more like syntax sugar for the old school constants concept.constprovides and that makes sense. - The block expression and implicit return style are a bit error-prone and confusing to get used to, I would have preferred explicit return. Also, it's not that readable IMO.

- If you have read my other post about Go, you might know that I'm not a fan of structs. Structs in Rust is very similar to structs in Golang. So like in Go, it would be easy to achieve unreadable struct structures. But fortunately, the structs in Rust seem much nicer than Go as you have functions, can use spread operator, shorthand syntax and so on here. Also, you can make structs which are Tuples. The structs in Rust are more like Java POJOs. I would have moved this to the liked section if having optional fields in structs where easier. Currently, you would have to wrap stuff in an

Optionalenum to do this. Also lifetimes :( - Given strings are the most used data types, it would have been nice to have a simpler way of working with strings(like in Golang) rather than working with the Vector types for mutable strings or slice types for immutable string literals. This makes code more verbose than it needs to be. This is more likely a compromise due to the fact that Rust is not garbage collected and has a concept of ownership to manage memory. https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/str.html - Edit: I have moved this point to nitpicks rather than dislikes after a discussion on the comments with robertorojasr

Conclusion

I like programming languages that focus more on simplicity rather than fancy syntax sugars and complex features. In my post "My reflections on Golang", I explain why I consider Golang to be too simple for my taste. Rust, on the other hand, is leaning towards the other side of the spectrum. While it is not as complex as Scala it is not as simple as Go as well. So its somewhere in between, not exactly the sweet spot but almost near that quite close to where JavaScript is maybe.

So overall I can say that there are more things in Rust for me to like than to dislike which is what I would expect from a nice programming language. Also, bear in mind that I'm not saying Rust should do anything differently or that there are better ways to do things that I complained about. I'm just saying that I don't like those things but I can live with it given the overall advantages. Also, I fully understand why some of those concepts are the way they are, those are mostly tradeoffs to focus on memory safety and performance.

But don't be fooled by what you see over the hood, Rust is definitely not something you should start with as your first programming language IMO, as it has a quite a lot of complex concepts and constructs underneath but if you are already familiar with programming then it shouldn't be an issue after banging your head on the doors a few times :P

So far I can say that I like Rust more than Golang even without implementing a real project with it and might choose Rust over Go for system programming use cases and for high-performance requirements.

Note: Some of my opinions have changed after using Rust more. Checkout my new post about the same

My second impression of Rust and why I think it's a great general-purpose language!

Deepu K Sasidharan ・ May 7 '21

If you like this article, please leave a like or a comment.

You can follow me on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Cover image credit: Image from Link Clark, The Rust team under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike License v3.0.

Top comments (71)

About the complex String data type, give it another look, is not unnecessary complexity but a result of the language focus, performance is important for Rust and the difference between str and String is not a trivial one, I'm a noob too and it also felt akward at first but now kinda make sense to me and is better understood when compared to an array and a vector. The array is stored in the stack, wich is much faster but you have to know their size (which mean type AND length) at compile time, making it more efficient but unable to grow or shrink at runtime; on the other hand a Vector is stored in the heap, slower but can be resized at runtime; the same goes to str, which is a reference or "pointer" to a memory space part of another str (stack) or a String (heap), that reference size is known at compile time (size of a memoty reference) hence it can be stored in the stack (faster). You could work just with Vecs and Strings and you would get the same "complexity" of more "high level" programming languages but you would lose a lot of potential performance. Is not an unnecessary complexity is just extra complexity because is a "lower level" language, it let you deal with memory management. Give it another read I came from Python and felt useless complexity but after some extra reading and thought it became clear, simple, elegant and awesome.

Of course I understand that difference and I think also coz of the fact there is no GC its important to make the distinction. So yes I agree that it is a required compromise but I still dislike it 😬

I'm not sure is about the absence of GC, AFAIK GC is about when to drop data, the distinction of arrays/vectors and str/Strings is more about where in memory the data is stored: fastest stack or runtime resizable heap. I'm not sure you can have the performance required for a systems PL without this extra complexity. You can't control something that you can't distinguish, I guess

I thought I read that somewhere. Need to double-check. It would be interesting to know how Go does it, which is also quite performant. Also to benchmark.

I don't see how could you avoid putting everything on the heap or having some runtime check; in both cases performance would be hit, we have to remmember that Golang and Rust have 2 different targets; Rust is a system PL first and general later while Golang is more a fast general PL first and maybe could be systems PL?, if your OS or browser is as little as 20% slower, you'll really notice. So for systems PL performance is not a luxury; I see Golang more like a power Python and Rust as a modern C; in realms like backend web dev they may overlap but the core target is very different

You are absolutely right. It is not really fair to compare them in the same scale. The problem is many people who learn one of these end up using it for everything that is thrown at them.

Maybe I'll start to like it more if I use it more 🙏

Also, I'll probably move it to Nitpick

I think rust must be put in context. This is intended to be a modern systems programming language(I've seen people have developed Operating Systems with it). This is definitely not for Web or Scripting, and so what seems to be complex is just an approach to tackle what's inherently complex in systems programming, I think. You would definitely not use it to write web apps, but if you have to write firewalls or network probes, I guess this is your best choice nowadays.

Yes, you are right, but I was not talking from building a web app per see, I was purely talking from the language perspective. Btw, Rust is the most impressive language I have come across.

Yep, it is impressive :) I know you weren't mentioning any application type, but to understand the language spirit, one must keep in his back-mind what problems it was meant to address. This was my point :)

I understand, but I feel some of my criticism are still valid even in a systems programming sense also Rust is definitely being used in more than systems now, like web assembly, CLIs and so on

Absolutely

You didn't mention "The Book"! It covers pretty much the whole language and its all what a rust beginner needs, oh and you can access it offline using

I didn't know this. Will check it out. Thanks

About functions not being 1st class citizens: you can use types like

impl Fn(u32, bool) -> u32. This means "return/take something that implementsFn(u32, bool) -> u32interface". The underlying implementation can be either a function or a closure.What is unfortunate, that you cannot write something like

type MyFn = impl Fn(u32, bool) -> u32. This is a nightly-only feature right now.But functions and closures are not interchangeable right? So functions still aren't first class citizens IMO

They are, the thing is, in Rust, callables are much more complicated than usual languages, at least what is exposed to the programmers.

We have 3 traits for callables,

FnOnce,FnandFnMut.All functions, function pointers and closures implements

FnOnce.All functions, function pointers and closures which does not move out of any captured variables implements

FnMut, indicating that it can be called by mutable reference.All functions, function pointers and closures which does not mutate or move out of any captured variables implements

Fn, indicating that it can be called by shared reference.The only way to have pass either function or function pointers or closures as parameter are using these traits, so on every context they are interchangeable.

Ok, I need to dwelve into this more. Now its more confusing to be honest. If they are same or interchangeable why have 2 concept/syntax? Why not keep it simple? Was there any specific reason to have both function and closures?

Well that's the bit it gets really confusing, they are not the same, but are interchangeable, when we say "function as first class citizen", we meant "callables as first class citizen", my hypothesis is because when the term was created, most major languages at the time had no more than one type of callable down on it's AST level that was functions, but that's not the point.

In Rust all functions have a type, and all closures are a type on it's own, but both are callables.

I have no knowledge why this way, but my instinct is that maybe something related to closures ability to capture the outer environment variables and the type system and optimizations.

I found the blog post that are talks about this:

stevedonovan.github.io/rustificati...

What do you mean by "interchangeable"? If a function accepts a parameter of type

impl Fn(...) -> ..., then this parameter can be either a function or a closure (so they are interchangeable). You can do many other other things with such types (return them, assign to variables, etc). IMO this is something that looks like 1st class functions.See my comment above

Shadowing is a bit of a misunderstood feature in rust. It came from ocaml which is the language rust was originally built on top of. You mention that shadowing is like mutation but it really isn't. Shadowing is not mutation because a shadowed let expression isn't an assignment. Each let binding binds a new value and it's irrelevant as to whether or not that variable name is the same as another one. In other words, the original immutable value can still exist especially when we are talking about multiple scopes (from functions and closures etc) while another value is shadowing it. It's sort of like how closures can freeze an environment and it starts to make more sense when you consider move semantics and stuff like that. Just as with any other immutable value, rather then change the value you replace it a different one.

Perhaps this is a feature that can be abused and used to generate bad habits but its not nearly as bad as you make it sound. Anyhow, you should look into it a bit more and consider the potential use cases (both good and bad). Even in inexperienced hands it's not that big of a deal.

I agree with most of your assessment though. I have taught rust for almost 3 years now, it's very easy to see the pros and the cons of the language especially when stacked against something like go. I like rust and I also like go, but when it comes to building something quickly, I'll choose go 9 times out of 10. Either way both are great tools to have in your programmer toolbelt. They are languages that will continue to define the future of the discipline going forward.

Hi thanks for the detailed response. As I said I do understand the reasoning behind it and I have no problems with shadowing in different scopes, my problem, as mentioned in post, is with shadowing in the same scope. I see more cons than pro in that case. Yes its not exactly mutation in theoritcal sense but can achieve the same result of accidental mutation with this.

Shadowing is most useful when you are parsing keyboard input:

It isn't the only resource.

For beginners take a look at these, both are linked to from rust-lang.org's "Learn" page:

Books:

More advanced, and mostly references:

I'm not sure why implicit return would be error prone since you have to specify the return type. Do you have an example?

Regarding this, it might be easier to think about everything in Rust having a type and a value. Thats why you can do things like:

This is true even when you don't explicitly return a type. A function without a specific return type actually returns a unit type

().Shadowing is a bit more complex than you've mentioned here, and does have its uses, though I think it's more often than not a bit of a smell if you're using it. Below is an example of how it can be used with scoping blocks, note that when the second x goes out of scope, the first one still exists. This is because you're not resetting it, you're creating a new var with

letand using that instead.The differences between

&strandStringare complex (not to mention&Stringand all the other types such asOsStringor raw data in a&[u8]). It definitely took me some time to get my head around, but all these different types actually perform very important functions.Lots of languages provide iterators as well as loops (also things like generators which Rust also provides but only in nightly atm), but I do agree again that having 3 different types of function is confusing, I still struggle with it.

TL;DR: I think your frustration at the complexities of the language are sound, however the more you use it I think the more you'll understand why they made those decisions (also, just wait until you hit lifetimes).

Thanks for the response. The reason I thought the implicit return is error-prone is as below

Both are valid as per compiler but have different meanings. I wasn't aware of the

()type and it makes a bit more sense, and ya seems like in most cases compiler would catch if you accidentally miss a;or add one in a block scope. Anyway, it was a nitpick and I think I'll retain it as such as I still don't like it. Maybe having a keyword likeyieldwould have been much nicer and explicit. I'm not a fan of anything implicit.For shadowing, I think you missed my point. I have no problem with shadowing in a different scope, it is indeed a good thing. My problem as mentioned in post is with same scope shadowing, see below

How is it any different from below in actual practice, it gives you a way to work around an immutable variable without marking it immutable. Again its a bit implicit IMO

About iterators and stuff, I would still prefer to have fewer ways to that

Also, I agree, as I use the language more I'm sure I would come to terms with these and I might even like some of them more, the same case with JavaScript, there is a lot of things I don't like about it but it is still one of my favorite languages.

Ya, I found the lifetime stuff to be strange but didn't form an opinion on them yet. So far it seems like a necessity due to language design.

The compiler will tell you exactly why your number, which is of the unit type (

()) won't work in a context expecting an integer. I don't think that's really so much of an issue. Also, you can post on users.rust-lang.org and probably be helped within 30 minutes with a very detailed explanation of your mistake and its fixes.Yes, I agree that Rust compiler is quite wonderful and when actually using it, it will not be a big deal. But from a readability standpoint I would still prefer explicit intent. To me good code should be readable even to someone not familiar with a language. Of course no language is perfect in that sense but one can dream of it right.

Thank you for sharing your experience of trying out Rust!

For optional struct fields, there's derive-new which gives you various

T::new()constructors. Derive is borrowed from Haskell, similar to Project Lombok for Java.The three

Fn*traits are a consequence of Rust's memory safety model built on linear logic, commonly known as lifetime / ownership. They are still first class values, meaning you can useletto bind them with a name and pass them in parameters like any other. They are just more complicated thanfunctionin JavaScript or closure in Java.Rust has

Fn,FnMutandFnOncein order to enforce at compile time rules which Java or JavaScript can only panic at run time:FnOncecan only run once. These can be functions likefree()in C orclose()inClosable. CallingFnOncetwice on the same object or context would not compile.thread::spawn()usesFnOnceto enforce that no references are passed to the new thread.FnMutcan mutate its captured state. This is most similar to a normal function in Java and JavaScript. There can be only oneFnMutcapturing the same binding existing at one time. If more, it would not compile.Fncannot mutate its captured state. This is somewhat analogous toconstfunction in C++.There's an order:

FnOnce < FnMut < Fn. AFn*can be used in the place of ones to its left.Wow. Thanks this is so far the most simple and straightforward explanation I got and now it makes more sense. I guess I would have to update the post to reflect what I learned about functions.

Concurrency in Rust is not tied to a particular threading module, and may not even be tied to threads at all. It is up to the programmer to choose how to concurrently execute their tasks.

Using futures, it is possible to join multiple futures together so that they execute concurrently from the same thread. When one future is blocked, the next future in the queue will be executed.

It's also possible to distribute them across a M:N thread pool, and interchangeably mix and match both approaches. Spawning a future will schedule it for execution on your executor. The executor may be based on a thread pool, or run on the same thread. Depending on which you choose, they may have

Sync/Sendrestrictions.Often times there's two different pools to spawn tasks to: non-blocking thread pools, and blocking thread pools. Tasks which block should be spawned on blocking pools so that they avoid blocking tasks on the non-blocking thread pool. The

async-stdcrate providesspawn_blockingfor that.Without futures, you may use crates like

rayonto distribute blocking tasks across a thread pool. This used to be the preferred threading model before the introduction of async/await with futures.There is an issue with your assertion that functions aren't first class. You can accept both functions and closures as input arguments, and return functions and closures as output arguments. Generics is required for returning closures, however, because closures are dynamically-created types.

Yes, concurrency in Rust is quite interesting

It comes down to personal preference, but I like the variable shadowing. When working with immutable types and stricter type system you tend to end up with a lot of temporary locals:

As in this case, you can often try to do more on one line, etc. But it’s handy to avoid creating a block expression.

Another thing I like about Rust is how it moves by default. This is similar to move semantics in c++11.

Agreed it is useful but to me it can be abused and can cause accidental errors as well. Maybe once you are experienced enough it might not be a problem, but then the same argument can be used for languages like JavaScript that lets you mutate by default. I can say that I have not had that issue as I'm experienced and I do not do it.