Written by Karthik Kalyanaraman✏️

Ever wondered what happens when you call ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'))?

We know that ReactDOM builds up the DOM tree under the hood and renders the application on the screen. But how does React actually build the DOM tree? And how does it update the tree when the app’s state changes?

In this post, I am going to start by explaining how React built the DOM tree until React 15.0.0, the pitfalls of that model, and how the new model from React 16.0.0 solved those problems. This post will cover a wide range of concepts that are purely internal implementation details and are not strictly necessary for actual frontend development using React.

Stack reconciler

Let’s start with our familiar ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root')).

The ReactDOM module will pass the <App/ > along to the reconciler. There are two questions here:

- What does

<App />refer to? - What is the reconciler?

Let’s unpack these two questions.

<App /> is a React element, and “elements describe the tree.”

“An element is a plain object describing a component instance or DOM node and its desired properties.” – React Blog

In other words, elements are not actual DOM nodes or component instances; they are a way to describe to React what kind of elements they are, what properties they hold, and who their children are.

This is where React’s real power lies. React abstracts away all the complex pieces of how to build, render, and manage the lifecycle of the actual DOM tree by itself, effectively making the life of the developer easier. To understand what this really means, let’s look at a traditional approach using object-oriented concepts.

In the typical object-oriented programming world, the developer needs to instantiate and manage the lifecycle of every DOM element. For instance, if you want to create a simple form and a submit button, the state management even for something as simple as this requires some effort from the developer.

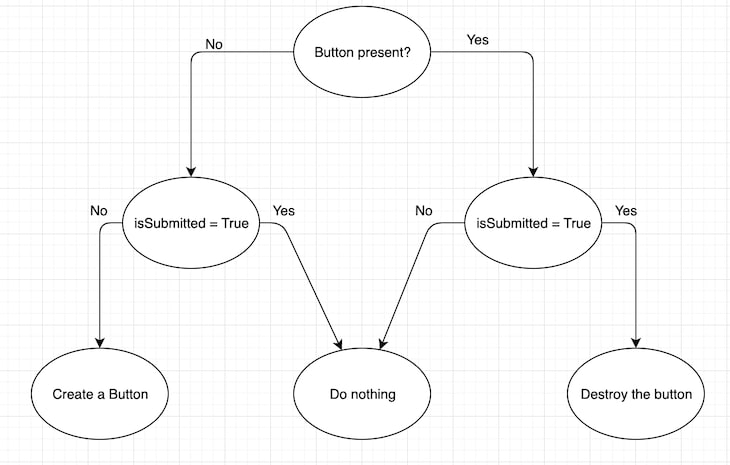

Let’s assume the Button component has a state variable, isSubmitted. The lifecycle of the Button component looks something like the flowchart below, where each state needs to be taken care of by the app:

This size of the flowchart and the number of lines of code grow exponentially as the number of states variables increase.

React has elements precisely to solve this problem. In React, there are two kinds of elements:

-

DOM element: When the element’s type is a string, e.g.,

<button class="okButton"> OK </button> -

Component element: When the type is a class or a function, e.g.,

<Button className="okButton"> OK </Button>, where<Button>is a either a class or a functional component. These are the typical React components we generally use

It is important to understand that both types are simple objects. They are mere descriptions of what needs to be rendered on the screen and don’t actually cause any rendering to happen when you create and instantiate them. This makes it easier for React to parse and traverse them to build the DOM tree. The actual rendering happens later when the traversing is finished.

When React encounters a class or a function component, it will ask that element what element it renders to based on its props. For instance, if the <App> component rendered this:

<Form>

<Button>

Submit

</Button>

</Form>

Then React will ask the <Form> and <Button> components what they render to based on their corresponding props. For instance, if the Form component is a functional component that looks like this:

const Form = (props) => {

return(

<div className="form">

{props.form}

</div>

)

}

React will call render() to know what elements it renders and will eventually see that it renders a <div> with a child. React will repeat this process until it knows the underlying DOM tag elements for every component on the page.

This exact process of recursively traversing a tree to know the underlying DOM tag elements of a React app’s component tree is known as reconciliation. By the end of the reconciliation, React knows the result of the DOM tree, and a renderer like react-dom or react-native applies the minimal set of changes necessary to update the DOM nodes

So this means that when you call ReactDOM.render() or setState(), React performs a reconciliation. In the case of setState, it performs a traversal and figures out what changed in the tree by diffing the new tree with the rendered tree. Then it applies those changes to the current tree, thereby updating the state corresponding to the setState() call.

Now that we understand what reconciliation is, let’s look at the pitfalls of this model.

Oh, by the way — why is this called the “stack” reconciler?

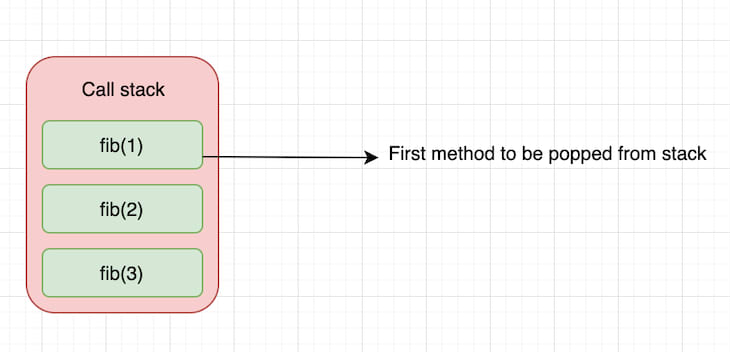

This name is derived from the “stack” data structure, which is a last-in, first-out mechanism. And what does stack have anything to do with what we just saw? Well, as it turns out, since we are effectively doing a recursion, it has everything to do with a stack.

Recursion

To understand why that’s the case, let’s take a simple example and see what happens in the call stack.

function fib(n) {

if (n < 2){

return n

}

return fib(n - 1) + fib (n - 2)

}

fib(10)

As we can see, the call stack pushes every call to fib() into the stack until it pops fib(1), which is the first function call to return. Then it continues pushing the recursive calls and pops again when it reaches the return statement. In this way, it effectively uses the call stack until fib(3) returns and becomes the last item to get popped from the stack.

The reconciliation algorithm we just saw is a purely recursive algorithm. An update results in the entire subtree being re-rendered immediately. While this works well, this has some limitations. As Andrew Clark notes:

- In a UI, it’s not necessary for every update to be applied immediately; in fact, doing so can be wasteful, causing frames to drop and degrading the user experience

- Different types of updates have different priorities — an animation update needs to complete more quickly than, say, an update from a data store

Now, what do we mean when we refer to dropped frames, and why is this a problem with the recursive approach? In order to grasp this, let me briefly explain what frame rate is and why it’s important from a user experience point of view.

Frame rate is the frequency at which consecutive images appear on a display. Everything we see on our computer screens are composed of images or frames played on the screen at a rate that appears instantaneous to the eye.

To understand what this means, think of the computer display as a flip-book, and the pages of the flip-book as frames played at some rate when you flip them. In other words, a computer display is nothing but an automatic flip-book that plays at all times when things are changing on the screen. If this doesn’t make sense, watch the video below.

Typically, for video to feel smooth and instantaneous to the human eye, the video needs to play at a rate of about 30 frames per second (FPS). Anything higher than that will give an even better experience. This is one of the prime reasons why gamers prefer higher frame rate for first-person shooter games, where precision is very important.

Having said that, most devices these days refresh their screens at 60 FPS — or, in other words, 1/60 = 16.67ms, which means a new frame is displayed every 16ms. This number is very important because if React renderer takes more than 16ms to render something on the screen, the browser will drop that frame.

In reality, however, the browser has housekeeping work to do, so all of your work needs to be completed inside 10ms. When you fail to meet this budget, the frame rate drop, and the content judders on screen. This is often referred to as jank, and it negatively impacts the user’s experience.

Of course, this is not a big cause of concern for static and textual content. But in the case of displaying animations, this number is critical. So if the React reconciliation algorithm traverses the entire App tree each time there is an update and re-renders it, and if that traversal takes more than 16ms, it will cause dropped frames, and dropped frames are bad.

This is a big reason why it would be nice to have updates categorized by priority and not blindly apply every update passed down to the reconciler. Also, another nice feature to have is the ability to pause and resume work in the next frame. This way, React will have better control over working with the 16ms budget it has for rendering.

This led the React team to rewrite the reconciliation algorithm, and the new algorithm is called Fiber. I hope now it makes sense as to how and why Fiber exists and what significance it holds. Let’s look at how Fiber works to solve this problem.

How Fiber works

Now that we know what motivated the development of Fiber, let’s summarize the features that are needed to achieve it.

Again, I am referring to Andrew Clark’s notes for this:

- Assign priority to different types of work

- Pause work and come back to it later

- Abort work if it’s no longer needed

- Reuse previously completed work

One of the challenges with implementing something like this is how the JavaScript engine works and to a little extent the lack of threads in the language. In order to understand this, let’s briefly explore how the JavaScript engine handles execution contexts.

JavaScript execution stack

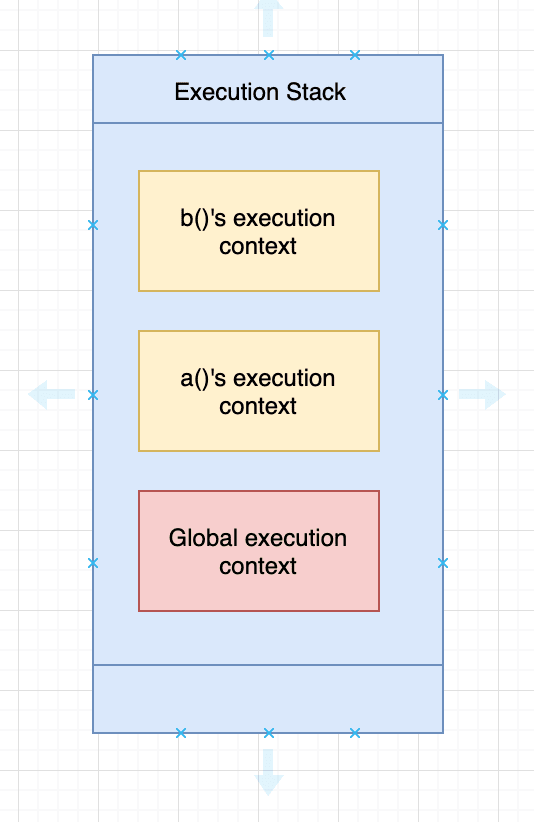

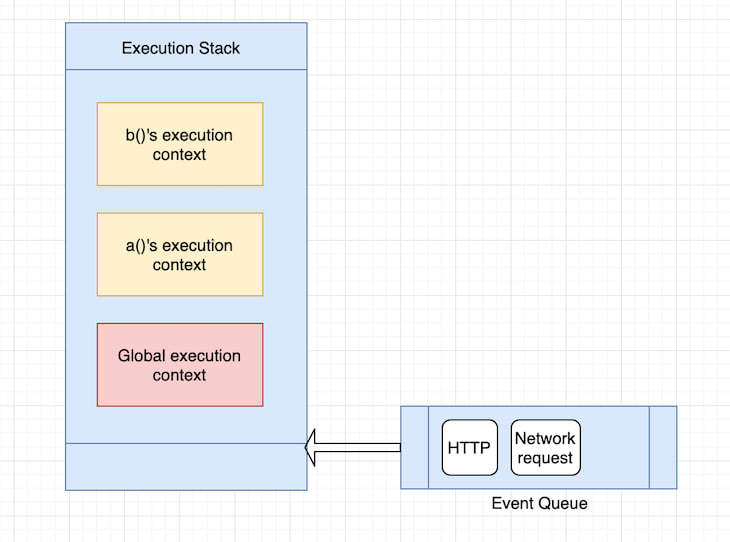

Whenever you write a function in JavaScript, the JS engine creates what we call function execution context. Also, each time the JS engine begins, it creates a global execution context that holds the global objects — for example, the window object in the browser and the global object in Node.js. Both these contexts are handled in JS using a stack data structure also known as the execution stack.

So, when you write something like this:

function a() {

console.log("i am a")

b()

}

function b() {

console.log("i am b")

}

a()

The JavaScript engine first creates a global execution context and pushes it into the execution stack. Then it creates a function execution context for the function a(). Since b() is called inside a(), it will create another function execution context for b() and push it into the stack.

When the function b() returns, the engine destroys the context of b(), and when we exit function a(), the context of a() is destroyed. The stack during execution looks like this:

But what happens when the browser makes an asynchronous event like an HTTP request? Does the JS engine stock the execution stack and handle the asynchronous event, or wait until the event completes?

The JS engine does something different here. On top of the execution stack, the JS engine has a queue data structure, also known as the event queue. The event queue handles asynchronous calls like HTTP or network events coming into the browser.

The way the JS engine handles the stuff in the queue is by waiting for the execution stack to become empty. So each time the execution stack becomes empty, the JS engine checks the event queue, pops items off the queue, and handles that event. It is important to note that the JS engine checks the event queue only when the execution stack is empty or the only item in the execution stack is the global execution context.

Although we call them asynchronous events, there is a subtle distinction here: the events are asynchronous with respect to when they arrive into the queue, but they’re not really asynchronous with respect to when they get actually get handled.

Coming back to our stack reconciler, when React traverses the tree, it is doing so in the execution stack. So when updates arrive, they arrive in the event queue (sort of). And only when the execution stack becomes empty, the updates get handled. This is precisely the problem Fiber solves by almost reimplementing the stack with intelligent capabilities — pausing and resuming, aborting, etc.

Again referencing Andrew Clark’s notes here:

“Fiber is reimplementation of the stack, specialized for React components. You can think of a single fiber as a virtual stack frame.

The advantage of reimplementing the stack is that you can keep stack frames in memory and execute them however (and whenever) you want. This is crucial for accomplishing the goals we have for scheduling.

Aside from scheduling, manually dealing with stack frames unlocks the potential for features such as concurrency and error boundaries. We will cover these topics in future sections.”

In simple terms, a fiber represents a unit of work with its own virtual stack. In the previous implementation of the reconciliation algorithm, React created a tree of objects (React elements) that are immutable and traversed the tree recursively.

In the current implementation, React creates a tree of fiber nodes that can be mutated. The fiber node effectively holds the component’s state, props, and the underlying DOM element it renders to.

And since fiber nodes can be mutated, React doesn’t need to recreate every node for updates — it can simply clone and update the node when there is an update. Also, in the case of a fiber tree, React doesn’t do a recursive traversal; instead, it creates a singly linked list and does a parent-first, depth-first traversal.

Singly linked list of fiber nodes

A fiber node represents a stack frame, but it also represents an instance of a React component. A fiber node comprises the following members:

Type

<div>, <span>, etc. for host components (string), and class or function for composite components.

Key

Same as the key we pass to the React element.

Child

Represents the element returned when we call render() on the component. For example:

const Name = (props) => {

return(

<div className="name">

{props.name}

</div>

)

}

The child of <Name> is <div> here as it returns a <div> element.

Sibling

Represents a case where render returns a list of elements.

const Name = (props) => {

return([<Customdiv1 />, <Customdiv2 />])

}

In the above case, <Customdiv1> and <Customdiv2> are the children of <Name>, which is the parent. The two children form a singly linked list.

Return

Represents the return back to the stack frame, which is logically a return back to the parent fiber node. Thus, it represents the parent.

pendingProps and memoizedProps

Memoization means storing the values of a function execution’s result so you can use it later on, thereby avoiding recomputation. pendingProps represents the props passed to the component, and memoizedProps gets initialized at the end of the execution stack, storing the props of this node.

When the incoming pendingProps are equal to memoizedProps, it signals that the fiber’s previous output can be reused, preventing unnecessary work.

pendingWorkPriority

A number indicating the priority of the work represented by the fiber. The ReactPriorityLevel module lists the different priority levels and what they represent. With the exception of NoWork, which is zero, a larger number indicates a lower priority.

For example, you could use the following function to check if a fiber’s priority is at least as high as the given level. The scheduler uses the priority field to search for the next unit of work to perform.

function matchesPriority(fiber, priority) {

return fiber.pendingWorkPriority !== 0 &&

fiber.pendingWorkPriority <= priority

}

Alternate

At any time, a component instance has at most two fibers that correspond to it: the current fiber and the in-progress fiber. The alternate of the current fiber is the fiber in progress, and the alternate of the fiber in progress is the current fiber. The current fiber represents what is rendered already, and the in-progress fiber is conceptually the stack frame that has not returned.

Output

The leaf nodes of a React application. They are specific to the rendering environment (e.g., in a browser app, they are div, span, etc.). In JSX, they are denoted using lowercase tag names.

Conceptually, the output of a fiber is the return value of a function. Every fiber eventually has output, but output is created only at the leaf nodes by host components. The output is then transferred up the tree.

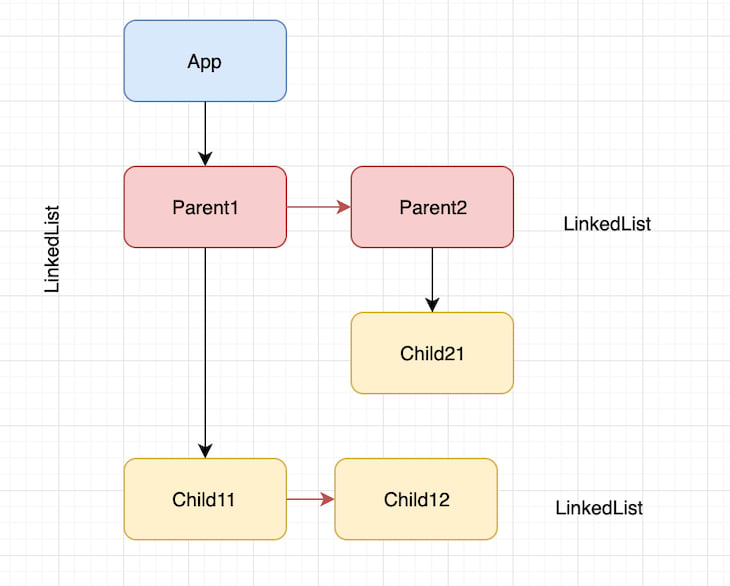

The output is eventually given to the renderer so that it can flush the changes to the rendering environment. For example, let’s look at how the fiber tree would look for an app whose code looks like this:

const Parent1 = (props) => {

return([<Child11 />, <Child12 />])

}

const Parent2 = (props) => {

return(<Child21 />)

}

class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

}

render() {

<div>

<Parent1 />

<Parent2 />

</div>

}

}

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'))

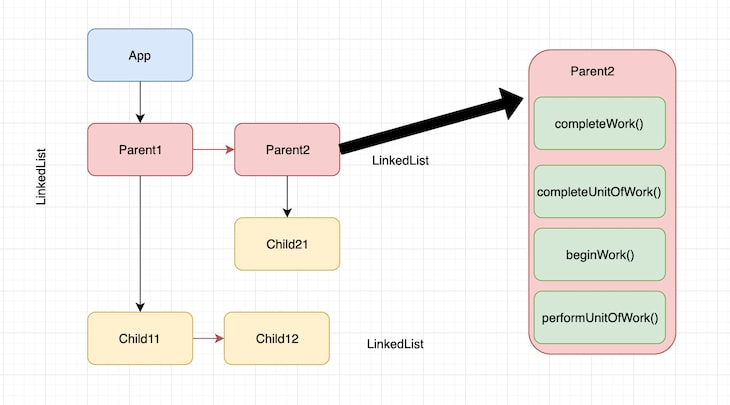

We can see that the fiber tree is composed of singly linked lists of child nodes linked to each other (sibling relationship) and a linked list of parent-to-child relationships. This tree can be traversed using a depth-first search.

Render phase

In order to understand how React builds this tree and performs the reconciliation algorithm on it, I decided to write a unit test in the React source code and attached a debugger to follow the process.

If you’re interested in this process, clone the React source code and navigate to this directory. Add a Jest test and attach a debugger. The test I wrote is a simple one that basically renders a button with text. When you click the button, the app destroys the button and renders a <div> with different text, so the text is a state variable here.

'use strict';

let React;

let ReactDOM;

describe('ReactUnderstanding', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

React = require('react');

ReactDOM = require('react-dom');

});

it('works', () => {

let instance;

class App extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = {

text: "hello"

}

}

handleClick = () => {

this.props.logger('before-setState', this.state.text);

this.setState({ text: "hi" })

this.props.logger('after-setState', this.state.text);

}

render() {

instance = this;

this.props.logger('render', this.state.text);

if(this.state.text === "hello") {

return (

<div>

<div>

<button onClick={this.handleClick.bind(this)}>

{this.state.text}

</button>

</div>

</div>

)} else {

return (

<div>

hello

</div>

)

}

}

}

const container = document.createElement('div');

const logger = jest.fn();

ReactDOM.render(<App logger={logger}/>, container);

console.log("clicking");

instance.handleClick();

console.log("clicked");

expect(container.innerHTML).toBe(

'<div>hello</div>'

)

expect(logger.mock.calls).toEqual(

[["render", "hello"],

["before-setState", "hello"],

["render", "hi"],

["after-setState", "hi"]]

);

})

});

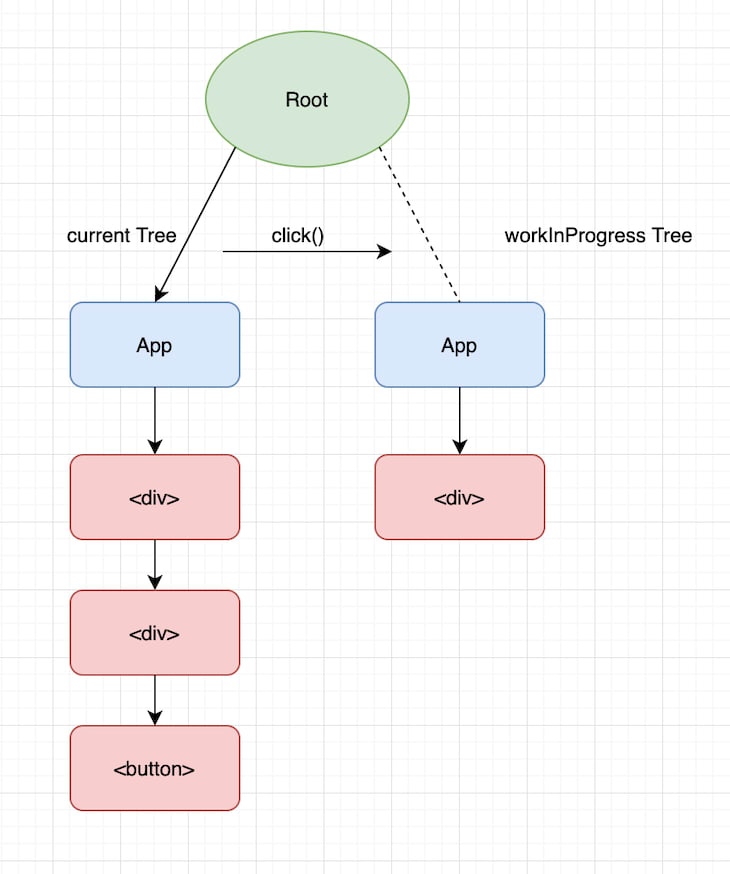

In the initial render, React creates a current tree, which is the tree that gets rendered initially.

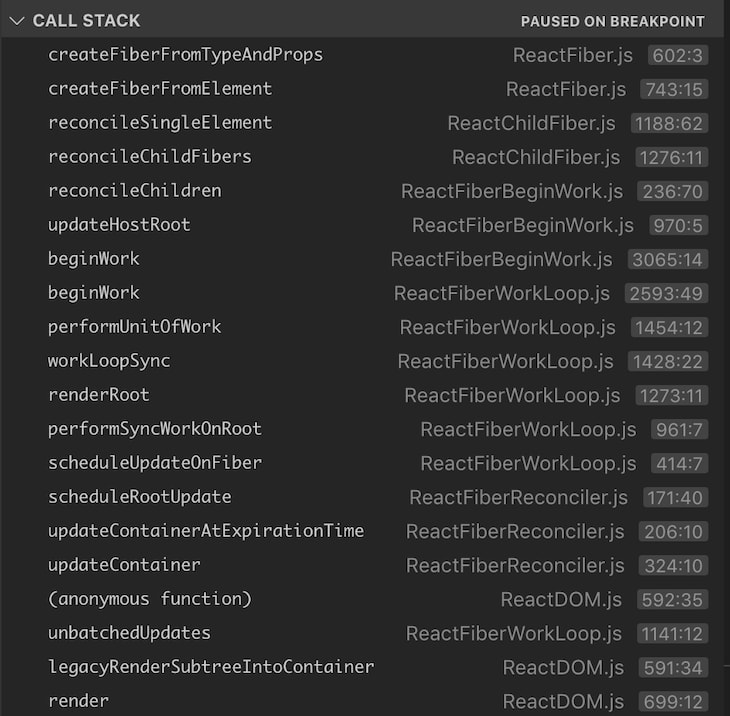

createFiberFromTypeAndProps() is the function that creates each React fiber using the data from the specific React element. When we run the test, put a breakpoint at this function, and look at the call stack, it looks something like this:

As we can see, the call stack tracks back to a render() call, which eventually goes down to createFiberFromTypeAndProps(). There are a few other functions that are of interest to us here: workLoopSync(), performUnitOfWork(), and beginWork().

function workLoopSync() {

// Already timed out, so perform work without checking if we need to yield.

while (workInProgress !== null) {

workInProgress = performUnitOfWork(workInProgress);

}

}

workLoopSync() is where React starts building up the tree, starting with the <App> node and recursively moving on to <div>, <div>, and <button>, which are the children of <App>. The workInProgress holds a reference to the next fiber node that has work to do.

performUnitOfWork() takes a fiber node as an input argument, gets the alternate of the node, and calls beginWork(). This is the equivalent to starting the execution of the function execution contexts in the execution stack.

When React builds the tree, beginWork() simply leads up to createFiberFromTypeAndProps() and creates the fiber nodes. React recursively performs work and eventually performUnitOfWork() returns a null, indicating that it has reached the end of the tree.

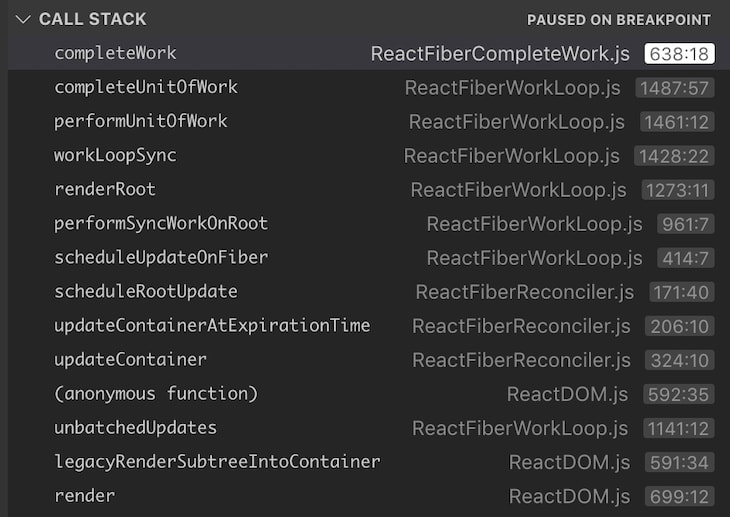

Now what happens when we do instance.handleClick(), which basically clicks the button and triggers a state update? In this case, React traverses the fiber tree, clones each node, and checks whether it needs to perform any work on each node. When we look at the call stack of this scenario, it looks something like this:

Although we did not see completeUnitOfWork() and completeWork() in the first call stack, we can see them here. Just like performUnitOfWork() and beginWork(), these two functions perform the completion part of the current execution which effectively means returning back to the stack.

As we can see, these four functions together perform the work of executing the unit of work, and also give control over the work being done currently, which is exactly what was missing in the stack reconciler. As we can see from the image below, each fiber node is composed of four phases required to complete that unit of work.

It’s important to note here that each node doesn’t move to completeUnitOfWork() until its children and siblings return completeWork(). For instance, it starts with performUnitOfWork() and beginWork() for <App/>, then moves on to performUnitOfWork() and beginWork() for Parent1, and so on. It comes back and completes the work on <App> once all the children of <App/> complete work.

This is when React completes its render phase. The tree that’s newly built based on the click() update is called the workInProgress tree. This is basically the draft tree waiting to be rendered.

Commit phase

Once the render phase completes, React moves on to the commit phase, where it basically swaps the root pointers of the current tree and workInProgress tree, thereby effectively swapping the current tree with the draft tree it built up based on the click() update.

Not just that, React also reuses the old current after swapping the pointer from Root to the workInProgress tree. The net effect of this optimized process is a smooth transition from the previous state of the app to the next state, and the next state, and so on.

And what about the 16ms frame time? React effectively runs an internal timer for each unit of work being performed and constantly monitors this time limit while performing the work. The moment the time runs out, React pauses the current unit of work being performed, hands the control back to the main thread, and lets the browser render whatever is finished at that point.

Then, in the next frame, React picks up where it left off and continues building the tree. Then, when it has enough time, it commits the workInProgress tree and completes the render.

Conclusion

To finish this off, I would highly recommend you watch this video from Lin Clark, wherein she explains this algorithm with nice animations for the purpose of better understanding.

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. Please feel free to leave comments or questions if you have any.

Editor's note: Seeing something wrong with this post? You can find the correct version here.

Plug: LogRocket, a DVR for web apps

LogRocket is a frontend logging tool that lets you replay problems as if they happened in your own browser. Instead of guessing why errors happen, or asking users for screenshots and log dumps, LogRocket lets you replay the session to quickly understand what went wrong. It works perfectly with any app, regardless of framework, and has plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

In addition to logging Redux actions and state, LogRocket records console logs, JavaScript errors, stacktraces, network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. It also instruments the DOM to record the HTML and CSS on the page, recreating pixel-perfect videos of even the most complex single-page apps.

Try it for free.

The post A deep dive into React Fiber internals appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

Top comments (3)

Love this post, gave me a lot more insight into what react fibre actually "means" other than just "it is better for performance." Also puts me in awe of the people who architected this feature, some very brilliant minds 🙂

This is so good man, nice post

Great post

I love these fundamental concepts