A cautionary tale of DevOps negligence & why it should be at the heart of any project

After recently finishing up a HUGE terraform refactor, I was left reflecting on why it’s essential to establish DevOps principles at the start of any large project; and the horror stories that can happen when it’s not.

Over the last decade, DevOps has gone from strength to strength and proven itself as a core component to many success stories. However despite this, in my experience as a software and cloud consultant, it’s still frequently overlooked and ignored in favour of application development.

I’m not talking about Waterfall architecture here, but rather some of the fundamental technical DevOps principles of:

Continuous Integration: establishing tools and process for continuously merging code back to a single code repository and single source of truth (e.g. git, subversion, mercurial, peer review)

Continuous Testing: establishing tools and process for continuously testing code during all stages of the software development lifecycle (e.g. unit tests, integrations tests, system tests, regression tests, chaos engineering)

Release Management: establishing tools and process for packaging and deploying releases

Infrastructure: infrastructure configuration, management, and infrastructure as code tools

Monitoring: performance monitoring and logs, end user experience

Continuous Delivery: automating the processes in software delivery

Many times I’ve seen these delayed or ignored until development starts reaching a critical mass, and developers start facing the deficits of not having these. They start getting messy merge conflicts. They need to work out how their application lives. What database do they need to connect to (and how do they manage this)? How do they deploy a new version without impacting the customer experience? Then there’s the dreaded cliff edge of deploying to production when they’ve only ever played around on smaller, more lenient dev/test environments.

I’ve seen this result in many “DevOps initiatives”, either in the middle of the application development or towards the end to try and ease some of the burden.

“What’s wrong with this?” I hear you ask.

While it is possible to establish these processes during the development lifecycle, or even afterwards, the time and effort to establish these fundamentals is exponentially increased. It can cause a great amount of refactoring that eats into time that could be better spent elsewhere.

Let’s look at a real life example to see how these principles can be easily overlooked, and the consequences of offsetting DevOps to a later stage. The example is loosely inspired by a project that I was bought on to rescue at a late stage, though largely exaggerated for comedic effect.

Case study — Project Whale

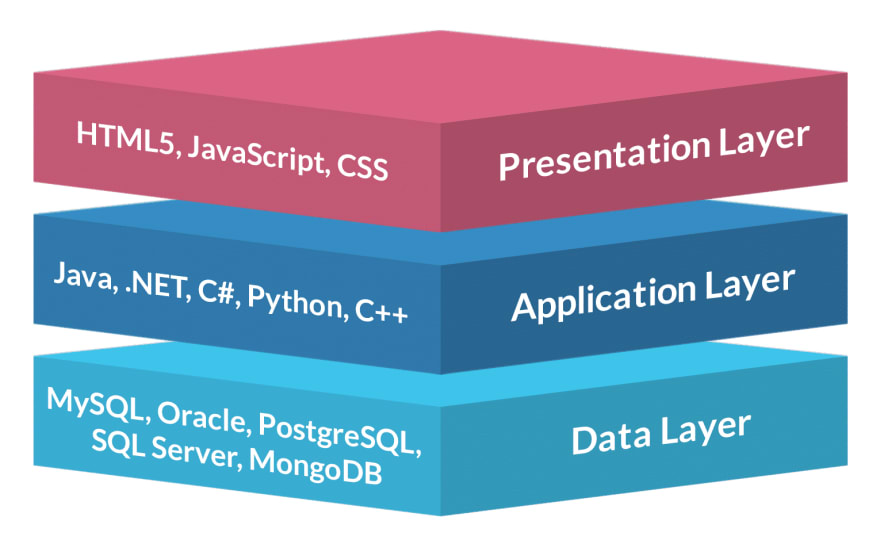

Say we have a standard 3 tier application called project Whale, with the 3 tiers representing;

- the presentation/UI/frontend,

- the application/business-logic/backend,

- and the data/storage/database.

The UI talks to the backend which in turn securely accesses the database.

During development of the frontend, we need to communicate with the backend, and likewise for the backend to database. The team decides to stand up a shared piece of infrastructure (a single EC2 instance) to run all three layers, which QA can also access to view features. Now they are able to continue their relevant development, whilst communicating to the necessary services.

Fast forward a few months and they’re approaching delivery time — great!!!

Everyone’s excited and the CEO’s about ready to pop a bottle of champagne. The developers need to run project Whale somewhere that’s accessible to the public internet. That EC2 they’ve been using for development seems like a great candidate — it’s already mostly set up with all the packages and utilities already configured by hand as and when the team realised they needed them.

They push the latest versions of the frontend and backend, clean out the database, and project Whale goes live.

As the champagne pours they start getting emails from customers about bugs in the frontend system. Small stuff, nothing that stops business, but things that could have easily been discovered if they’d invested in continuous testing, and it’s enough that requires a new version of Whale to be deployed. Except now they’ve got customers on the live system, and deploying a new version means taking the old one offline while they switch over.

They’re left with a couple options:

- Deploy anyway and annoy customers

- Schedule a deployment overnight when traffic is low and annoy the developers who have to pull an all-nighter

- Start up a fresh EC2 instance and turn off the old one

The latter is clearly the best option for reducing downtime and keeping people happy, however upon doing this they realise all those little packages and utilities need to be set up again and reconfigured, and the last time anyone did this was 4 months ago. They documented it though, so even though it takes hours they’re able to get the new EC2 up with the new version of Whale deployed — this is where release management would have really been beneficial right?

Except now customers are complaining more than before, because they can’t login and are being told that they don’t have an account — the database!

Yup, they forgot about the data. While they were able to get the database running on the new EC2, they forgot about the customer account data that had been written to the old database on the old instance — this is a fresh database without any customer information.

BATTLESTATIONS!!!!

As fires seem to spread they realise their mistake, they should have isolated the database from the rest of the stack, so they could deploy any number of EC2 instances running Whale and simply connect it to a persistent database. But none of them are database or networking experts and unsure how to expose the database connection across servers — this is where Infrastructure as Code could have really helped.

Let’s skip forward a few days, all the fires are now just smouldering pits. They managed to provision a managed database service in the form of AWS RDS and got some help with the networking. Whale is really gaining traction, and customers love it, then overnight the user base explodes. They go from tens of customers to a few thousand and are featured on the front page of Reddit.

Then it happens.

Everything just slows down and stops. No alarms, no errors, just nothing. Customers are once again adrift, and causing one hell of a Twitter storm. What happened? There were no recent code changes.

It turns out that they gained more users than the single EC2 instance could handle. As more users joined and started using Whale, the backend started dumping logs at an increased rate filling up the EC2’s local file storage, taking both it and the frontend offline. Something that could have been easily avoided if they’d shipped logs off to a Monitoring solution.

Now they need to work out how to scale Whale over multiple EC2 instances at once, and how to get the logs off of the local EC2 file system to somewhere else. All while Whale is currently offline, and they still haven’t got an automated solution for deploying new versions without users experiencing some downtime. This would have been a trivial task if they had embraced continuous delivery and used containers to run Whale’s individual layers on ECS or Fargate — where shipping logs and autoscaling is given out of the box.

So now the team is left trying to split the frontend and backend, and refactor both applications to run in containers. Then on the infrastructure side they need to set up and configure:

- ECS/Farage Clusters to run the containers,

- Log routing and monitoring to CloudWatch,

- Auto scaling for their customer demands,

- Networking to their RDS instance,

- Deployment strategies for rolling out new versions.

To make matters worse they’re still running on a single environment — so either they’d have to make all of these changes on their “production” environment, or spin up a separate isolated development environment, which to ensure both environments are identical. They’d really have to invest in Infrastructure as Code.

This is a HUGE amount of technical debt for a small team which could easily stop any future development or bug fixes for 6 months or more — something that could easily sink the project, team, and potentially the company.

How DevOps principles could have helped?

Now, as I said, this isn’t about Waterfall design, but more about involving DevOps principles from the start. By applying DevOps principles from the beginning they could have avoided some of these situations.

By embracing Continuous Integration they could have:

- Ensured that any code integrated back to their main branch be fully tested prior to deployment; avoiding small bugs interfering with the customer experience.

By embracing Continuous Testing they could have:

- Created isolated Development, QA, and Production environments. This would have ensured that development versions of Whale could be deployed and acceptance tested, rather than pushing untested versions onto their live customer facing Production environment.

By embracing Infrastructure they could have:

- Spun up a managed database, such as RDS, instead of running their own on the EC2 server; avoiding losing valuable customer data.

- Leveraged container autoscaling to easily scale horizontally, instead of running everything on a single server; avoiding outages due to increased customer usage.

- Codified their cloud estate using IaC (Infrastructure as Code) so that they could easily provision multiple dev/qa/prod environments, rather than trying to repeat months old work to manually configure a second environment.

By embracing Monitoring they could have:

- Shipped logs to persistent storage such as CloudWatch, instead of leaving them on the single server; avoiding filling up the local application storage and taking Whale offline.

By embracing both Release Management and Continuous Delivery they could have:

- Eased the release and roll out of the different layers in isolation; avoiding the lengthy rewrite to separate the backend and frontend layers, and enabling each layer to be developed at its own cadence.

All of these problems could have been avoided if they had merely considered the wider picture outside of their own application code, and embracing these principles from the beginning, when the cost and burden would have been mere hours, rather than months.

Summary

To me this is one of the biggest strengths of DevOps; by embracing DevOps principles we start thinking at a larger scale and building applications in a more holistic view. DevOps doesn’t require teams of DevOps engineers setting barriers or lengthy processes; it just requires individuals and teams to embrace those principles to build better, more scalable, and robust systems.

Now, of course that’s not all DevOps is. It also involves building a no blame culture, doing technical postmortems, and involving the wider business to understand that code doesn’t stop at the application level. However, I really wanted to highlight the impact that ignoring DevOps can have on development and projects.

It’s not all doom and gloom though, we can still bring DevOps into an existing project, but the technical burden will be increased exponentially, and would require significant investment both in time and resource.

So the next time you’re thinking of starting a new project, product, or initiative; don’t put off applying these principles. DevOps and application development are two pieces of the same puzzle. They need to be done together, in tandem, rather than ignored until a later date, because by that later date, your product could already be dead in the water.

Do you have any experiences of where DevOps was applied a little too late? If you are interested in learning more about DevOps, please check out my other blogs on my website, Manta Innovations and reach out to me on Twitter @ Joel Lutman

Top comments (1)

Epic story! Thanks for sharing Joel.